The month of July 2023, saw an interesting instance of counterprogramming in Hollywood history. Two big-budget films produced by rival production camps- Warner Brothers and Universal Pictures- went head to head in cinemas targeting aesthetically opposite fan bases. Barbie by Greta Gerwig and Oppenheimer directed by Christopher Nolan had a lot in common, yet they could not be more different from each other. Both films were much anticipated, big-budget multi-starrers from two critically acclaimed directors who specialise in vastly different genres. On top of this, both Barbie and Oppenheimer were slated for release on the same day- 21st July.

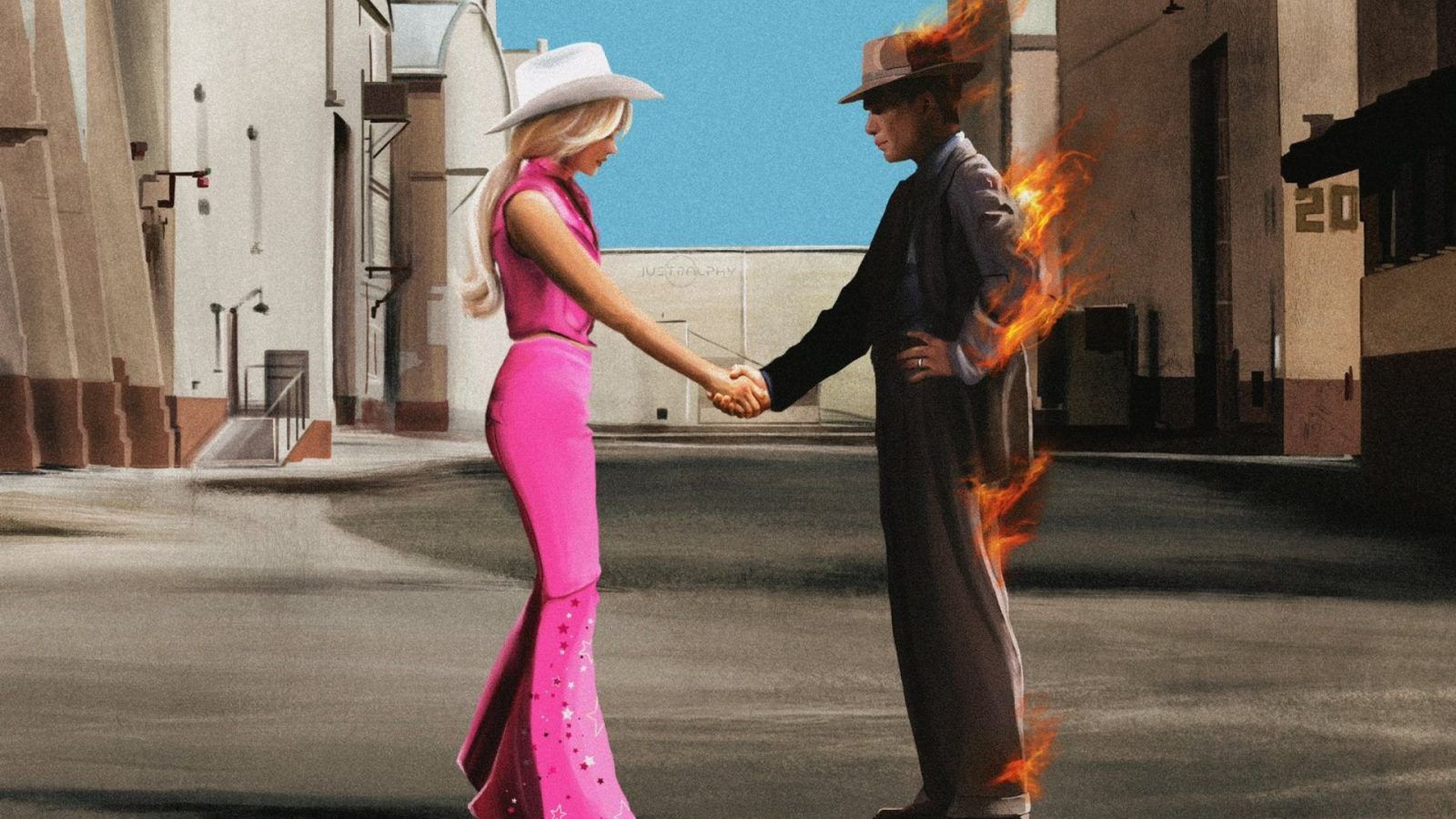

However, in spite of the many similarities shared by both films, they belong to very different genres, exhibiting almost contradictory aesthetics and moods. Barbie is a fun adventure-comedy that explores the concepts of feminism and questions the neoliberal capitalism of corporations, albeit with generous splashes of bubblegum pink thrown in for good measure. On the other hand, Oppenheimer is a period piece, a dark and sombre biopic of nuclear physicist J. Robert. Oppenheimer, the creator of the atom bomb, and a sharp political and psychological drama all rolled into one.

Understanding the Barbenheimer phenomenon as a cultural moment

What the dual release of these two aesthetically antithetical films led to, would go down in film and pop culture history. The Barbenheimer cultural phenomenon is an internet and cultural trend started by fans of both films. A portmanteau of the words Barbie and Oppenheimer, it is a term that has not only become popular among certified cinephiles but also has found relevance in the current cultural discourse, especially for a generation which is chronically online.

Passionate, young film lovers, rejuvenated in their love for cinema and theatres after the two year long hiatus caused by the pandemic, made plans to turn up in cinema halls wearing myriad hues of pink for Barbie and dark muted tones for Oppenheimer. Some even wanted to catch both films in a single day, hurrying to multiplex washrooms for a quick genre-appropriate costume change before the second film starts.

Passionate, young film lovers, rejuvenated in their love for cinema and theatres after the two year long hiatus caused by the pandemic, made plans to turn up in cinema halls wearing myriad hues of pink for Barbie and dark muted tones for Oppenheimer. Some even wanted to catch both films in a single day, hurrying to multiplex washrooms for a quick genre-appropriate costume change before the second film starts.

While it was heartening to witness the festivities surrounding films, it is important to note the differences between the two target fan bases of Barbie and Oppenheimer. Barbie directed by Greta Gerwig, in all its pink-tinged glory, is a feminist clarion call to end patriarchy. The film attempts a feminist reclamation of the famous (and at times controversial) Barbie doll created by Ruth Handler and owned by the Mattel corporation.

Primarily targeted towards women who have been historically oppressed by patriarchy, the film condemns the abject vilification and degradation of all things feminine and girly, urging young women to embrace and feel powerful in their femininity. Through a metacinematic approach, the film also criticises corporate capitalism and the warped patriarchal double standards that exist for women in today’s neoliberal world. Judging by the teeming population of film enthusiasts, both male and female, all decked up in shades of pink, it is clear that Barbie succeeded in conveying its message to a great extent.

On the other hand, Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer attempts to examine history, power dynamics and the politics of scientific discovery. Marketed mainly towards STEM enthusiasts who also take an interest in history, Oppenheimer, like most of Nolan’s films, had aimed for a mostly male fan base. Addressing burning political questions of nuclear war and world dominance, Oppenheimer also manages to examine and explore the human condition and what it means to be powerful yet powerless at the same time.

Is Barbenheimer the latest battle of the sexes?

In order to understand the Barbenheimer phenomenon, it is imperative to examine how it reasserts the binaries between the masculine (Oppenheimer) and the feminine (Barbie). STEM chauvinists and self-proclaimed Nolan fanboys have already dismissed Barbie as a “silly” little girls’ film. Ben Shapiro’s scathing yet baseless criticism of Barbie on YouTube, deeming it to be a ‘man-hating’ film is a testament to that. An example of a more recent battle of the sexes and their differing and often opposing preferences, some aspects of the Barbenheimer phenomenon attempt to gender something like cinema, an artistic form that has the potential to transcend all gender stereotypes and barriers.

Dividing the Barbie and Oppenheimer fan bases on the basis of their sex and disparaging Barbie enthusiasts for having conventionally feminine interests is a sad reassertion of the highly problematic gender binary and gender roles.

It must be understood that it is not impossible to like both films equally, at the same time. Owing to the varying styles, forms, genres and aesthetics, it is only natural that both films cater to different needs and moods, variables that are not dependent on one’s assigned gender.

The problem with the Barbenheimer binary

By dividing the Barbie and Oppenheimer fan bases into water-tight compartments based solely on gender and assuming that ‘never shall the twain meet’, some proponents of the Barbenheimer craze run the risk of erasing the large intersection of individuals who enjoyed and are enthusiastic about both films, which are brilliant in their own right. It is indeed hilarious that a section of society is under the prejudiced assumption that individuals who like the Barbie-core aesthetic cannot harbour a deep interest in nuclear physics.

It is also strange to see certain people (who am I kidding? It is a section of straight cis men, of course) think that out of the two films, only Oppenheimer dealt with pressing political issues of our times while Barbie was just a flick about a bunch of “silly” girls parading in pink for a bunch of “silly” girls parading in pink on the other side of the screen, in the Real World. It is not surprising to see straight men denying the existence of a pressing socio-political issue like the patriarchy because it does not affect them. Naturally, it is impossible for these men to comprehend that beneath its sparkly pink-toned glitz of bright bubblegum pop, Barbie is a poignant satire of life under patriarchy and neoliberalism, a lived reality for all women.

The gendering of film that denigrates conventionally feminine interests has always been a part of the cinema culture. Binaristic gendering is apparent in every aspect of human life under consumerism. Right from clothes and books to jobs and interests, the capitalist market, joining hands with its best friend, the good old patriarchy, decides what people can or cannot consume. The normative interpretation of the Barbenheimer phenomenon is a testament to that.

The gendering of film that denigrates conventionally feminine interests has always been a part of cinema cultures. Binaristic gendering is apparent in every aspect of human life under consumerism. Right from clothes and books to jobs and interests, the capitalist market, joining hands with its best friend, the good old patriarchy, decides what people can or cannot consume. The normative interpretation of the Barbenheimer phenomenon is testament to that.

However, despite misogynistic attacks and attempts at gendering from dudebros like Ben Shapiro and Piers Morgan, it is heartening to see how young film enthusiasts, irrespective of gender, enjoyed and appreciated Barbie and Oppenheimer. Moreover, seeing Cilian Murphy and Greta Gerwig refusing to participate in the imposed competition by hyping up each other’s films, in spite of generic differences, truly goes to show how culturally significant this moment is. These instances make us realise what an important impact films can have to foster diversity and inclusivity, one cinema ticket at a time.

About the author(s)

Ananya Ray has completed her Masters in English from Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India. A published poet, intersectional activist and academic author, she has a keen interest in gender, politics and Postcolonialism.