In the forests of South India lived a man who wreaked havoc for over three decades. The two-decade-long manhunt in pursuit of Veerappan, who was variously known as the King of the Forest, the Robinhood, or the Forest Angel, was the costliest one in the history of India.

In his new docu-series, The Hunt For Veerappan, Selvamani Selvaraj depicts a riveting account of the bandit’s story through the lens of individuals directly connected to the manhunt and those intimately related to Veerappan.

Veerappan was a poacher, a sandalwood smuggler and a brigand who spent the majority of his life in the jungle, fleeing from the Karnataka and Tamil Nadu police. Having poached thousands of tuskers to sell ivory and having smuggled crores worth of sandalwood, Veerappan became a menace who was impossible to get hold of.

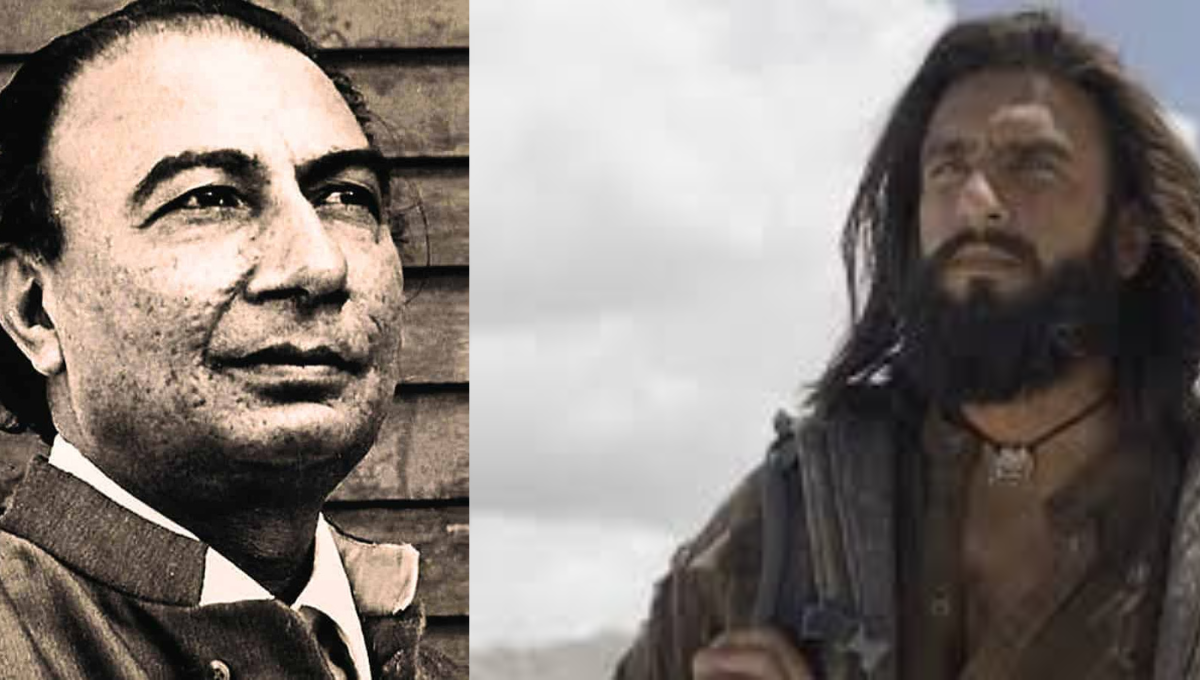

The four-part docu-series opens with an account of Veerappan’s wife, Muthulakshmi, whose uncritical view of her husband is directly opposed to the perspectives of police officers and government officials interviewed. She not only loved him but worshipped him enough to justify his actions.

The Special Task Force (STF) was set up to nab Veerappan and changed faces over the years. One can observe the extent of their desperation and how their operations became more strategic and tactical over time. Muthulaksmi’s point of view, the persistent failure of the STF in capturing Veerappan, the interviews of villagers, journalists and the police that praise Veerappan for his fearlessness and intelligence, and his deification by numerous people paint a picture of grandeur and might.

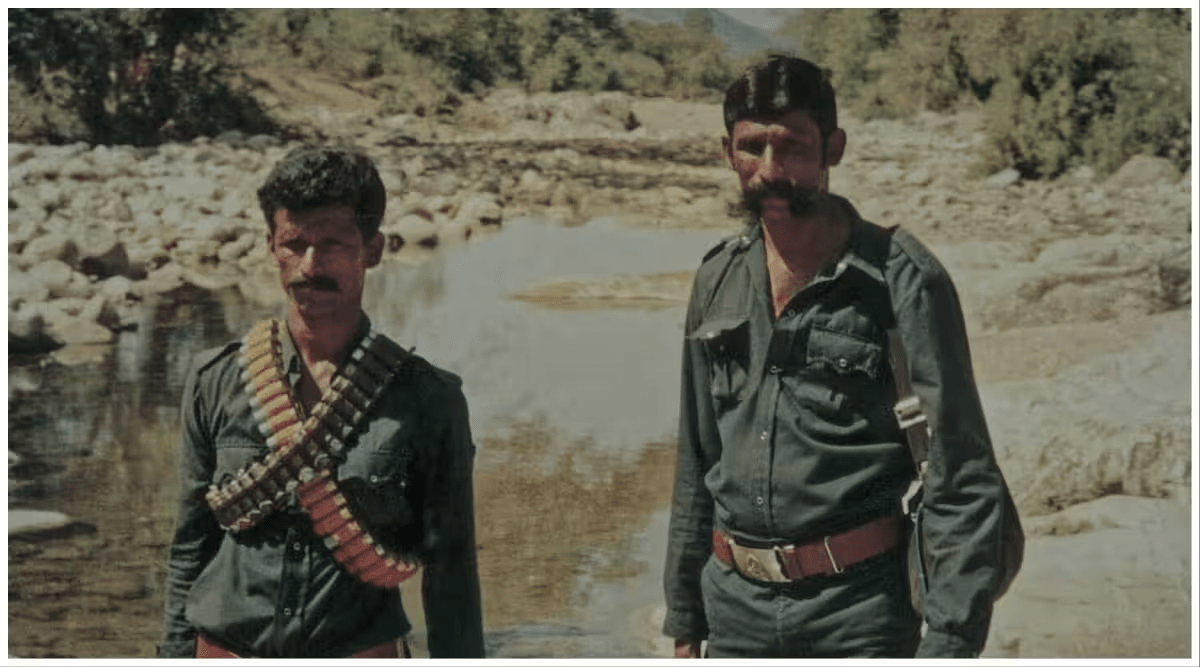

The archival images, footage, and audio recordings expertly weave through the narrative to provide it credibility. A viewer may experience the sense of getting closer to the actual figure of Veerappan as the documentary progresses.

This has largely to do with the content and quality of the images and recordings which keep getting closer in source to Veerappan: his voice can be heard through cassettes, and his pictures and videos become clearer. While a documentary, shots depicting Muthulakshmi and journalists walking in slow-motion, the shadowed figure of the trader whose face is expertly veiled through the use of lighting, and the somewhat dramatic quality of interviewees’ narration, and the music give this story an almost mythical treatment.

Treading the line between the glorification of a figure and the figure’s true depiction is a tricky one. The documentary becomes the medium through which the director presents the myriad perceptions regarding Veerappan.

The officers in question boast of their encounters and their success in avenging their deceased comrades by killing people. Some express awe and smugness at having nabbed and killed Veerappan, while others simply regard him with wonder and disgust.

Unlike other true crime documentaries where the subject in question is an exception, an outlier, perhaps a psychopath whose peculiar nature and actions become the sole fascination, a story like Veerappan’s is much broader in scope.

The first two episodes give a background of who Veerappan was and the sheer bloodbath that was caused by him and the police. His rebellious instinct and need for justice are only eluded to but the third and fourth episodes firmly place him as an unisolated individual who can be born again with a different face. Among all the voices, we have Anubraj, a former gang member, and Maaran, an ex-militant, that provides a greater depth to the inquiry into Veerappan’s character.

Maaran opens by posing an important question, ‘When a government and state media brands someone a criminal, one needs to look carefully into the reasons for such crimes to happen. Was he criminal by nature or was he made into one.’

In a similar vein, Anubraj expresses, ‘Veerappan may have died. But the reason for a Veerappan to exist in the first place, those social issues, were they ever discussed? Huge violations done by government forces were buried deep inside the forest. Lives ripped apart in the name of Veerappan. So many unspoken deaths, molestations, lives destroyed and buried like the truth in this case… People saw Veerappan as a hero and a leader. It is the bitter and sad truth.’

Anubraj, Muthulakshmi’s consistent presence in the telling of his story is crucial. The story is as much about her as it is about Veerappan since her life and identity are so wound up with his. She regards him as the bravest man, as an invincible force who did what he did to survive. Interrupting all her admiration, the interviewer declares, ‘To me, the act of killing is not bravery.’

Muthulaksmi has nothing to say to that.

“The Revolutionary,” portrays his journey of developing a vision through education that the militants provide him with of revolutions, movements, and ideologies: Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, Mao Zedong Lenin, Marx, Etc. become his staple. He is slowly emboldened with dreams of an independent Tamil Nation, which is reflected in his demands to the government when he kidnaps Dr Rajkumar, a cultural phenomenon of Karnataka.

What comes through is a man who is immensely cruel and animal-like, who has rationalised his actions as those done in retaliation to the atrocities of the police, as actions that were necessary because he had no way out. The killings were also his attempts at justice. The means justified the ends.

The police’s desperation to get hold of Veerappan and the degree of pride and the lack of remorse that the interviewed officials evince comes across as a glaring reflection of Veerappan’s tendencies to commit crimes in the name of justice: one set of crimes is state-sanctioned and the others are not.

Up close, in everyday life, many perceived him as a tender human being with a capacity for kindness for those he loved. At the end of the third episode, one sees that tenderness come through when he decides he wants to live a peaceful life with his family.

Veerappan was no ordinary man but his aspirations and emotions were very human. The documentary shows that the hideous and the humane can coexist within one individual.

About the author(s)

Shakti (she/her) is an English major and an aspiring tea sommelier. She loves reading poetry and drama and can be found with a Kindle most time. She intends to become a teacher of humanities and is passionate about literature, films, politics, and history. In her free time, she has been caught watching cringe content, however, she fervently denies these claims.