“I want a world where friendship is appreciated as a form of romance. I want a world where when people ask if we are seeing anyone we can list the names of all of our best friends and no one will bat an eyelid. I want monuments and holidays and certificates and ceremonies to commemorate friendship.” — Alok Vaid-Menon

The first time I read these lines last year, I felt a penny drop inside my head. That all my life my friendships have been as giving—if not more—than my romances. Yet, I had nearly shoved them aside in my twenties, and spent a lot of vim and vigour in search of ‘the great love of my life.’

The era of being single and ashamed

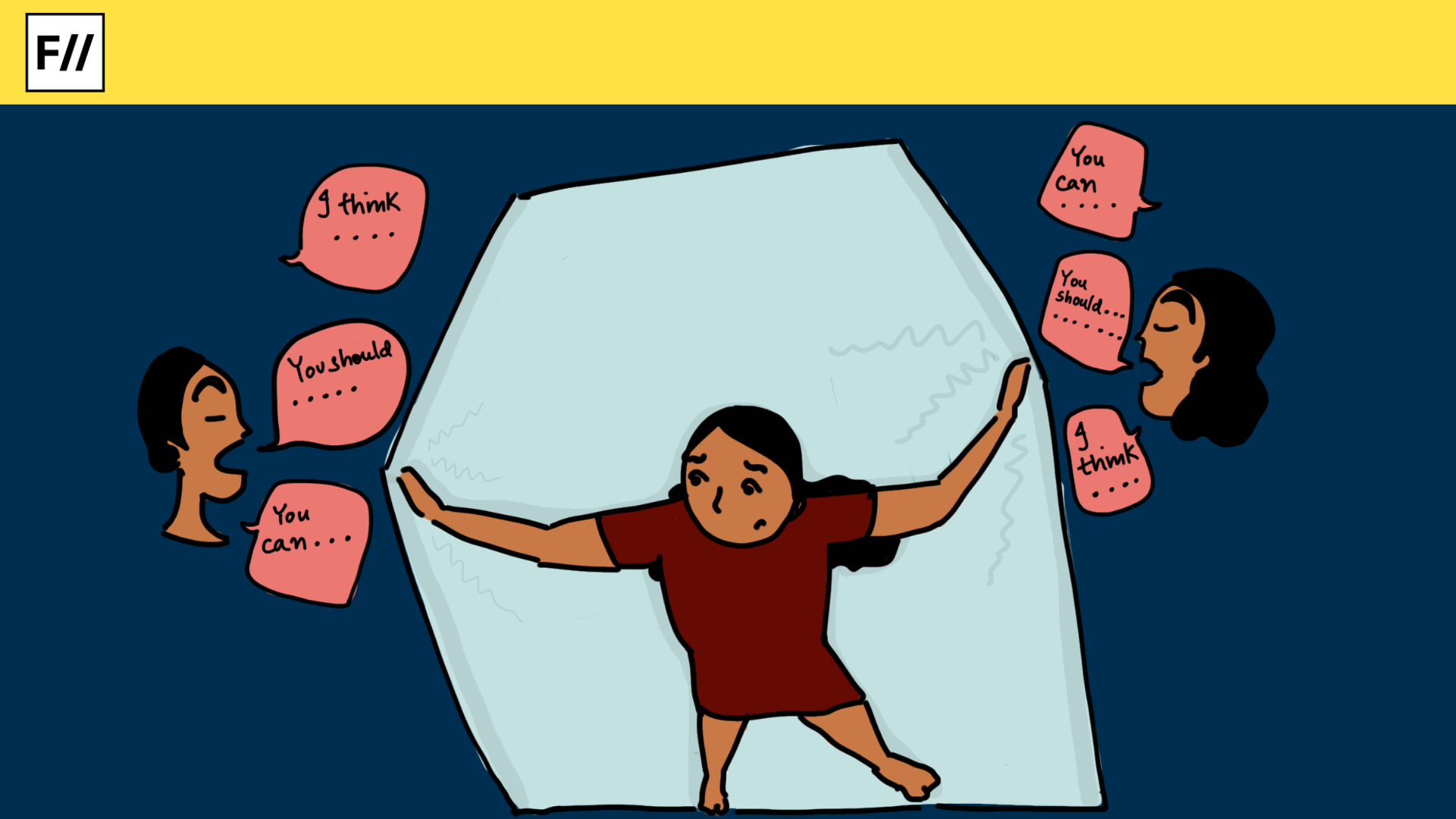

As another “Friendship’s Day month,” winds down without much fanfare, I am increasingly thinking about the eclectic selection of friends I have collected over the years. While my friendships have always nourished and sustained me, I have also been conspicuously single until my mid-twenties. Since singlehood didn’t transpire through lack of opportunity, I increasingly found myself concluding I must have ‘intimacy issues.’

I told myself, I must lack the skills to form intimate human connections.

Popular culture-confirmed my suspicions. The Bridget Jones franchise comes to mind. Bridget, despite having a job and supportive friends, is consumed by her desire to find that mythical unicorn of all romantic comedies, ‘the One.’ To deflect peers who took a continued interest in my ‘hopeless love life,’ I generously used self-deprecating humour. I began calling myself ‘romantically challenged,’ just like the cutesy bumbling Bridget Jones.

It was much later, that I would see ‘single-shaming‘—negative biases around singlehood that lead to discrimination against single people—as a real thing, and that I had survived it. Only with the safe objective distance of my thirties can I look back and see the anxiety that haunted most of my tweens. The dread of being a romantic failure. Of ending up alone.

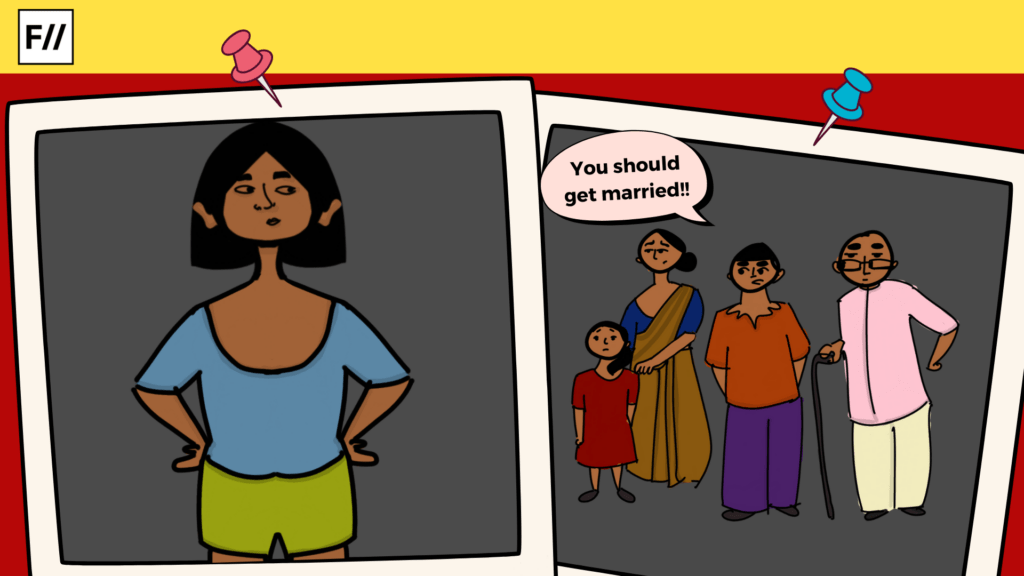

With this not-so-flattering self-image, I inched into my twenties. Inside my mind, Bridget Jones swirled around with all the Jane Austen novels I had ever read. Not having a romantic partner began feeling like a personal failure. Barely veiled comments from relatives about my ‘future‘—read marriage—didn’t help matters. It was enough to send me into a tizzy about my imminent future: as an ‘old maid.’ Off I went, hurtling down a dangerous path of finding out the choicest ‘red flags‘ and forcing them to wear the Cinderella shoes of being ‘my One.’

It was much later, that I would see ‘single-shaming,’—negative biases around singlehood that lead to discrimination against single people—as a real thing, and that I had survived it. Only with the safe objective distance of my thirties can I look back and see the anxiety that haunted most of my tweens. The dread of being a romantic failure. Of ending up alone.

Understanding amatonormativity

The irony of the situation was, that while I bungled about my romantic wasteland, I was never quite alone. I have often joked, that were I to write a memoir it would be called, “With a little help from my friends.” Even though my most jagged days, my friends were there for me. They checked in with me and patiently listened to my frantic hour-long audio notes. They forced me out of the house when depression got the better of me. They loved me fiercely when my self-loathing got too loud.

In retrospect, I realised I wasn’t particularly lacking in love and solidarity while I condemned myself as a lonely single person.

This is where Vaid-Menon’s lyrical words—demanding friendship to be viewed as a form of commitment, of intimacy—rent through me like a lightning bolt of epiphany. Because my friendships have time and again saved me. Brought me back from the brink.

What if I was never deficient in anything? What if a culture that was solely focused on romantic love as a cherished goal of adult life conditioned me to believe that? What if I lost sight of what I had—a multitude of life-affirming friendships—in pursuit of what I was told was more important?

Just like other normative belief systems, amatonormativity conditions and encourages us to live life according to a certain script. It excludes all other forms of intimacies from consideration and puts the onus of a successful life on finding a romantic connection and sustaining it. It gives rise to the ‘relationship escalator,’ – which says adults find ‘the One‘—their ideal all-in-one romantic partner—marry them, have children with them, and stay together in a cocoon of happily-ever-after.

Thanks to the discourse around how asexual and aromantic folx experience intimacies, there now exists an actual word for this bias that idealises ‘romantic love‘ as a goal towards human fulfilment. “Amatonormativity is a long word that philosopher Elizabeth Brake came up with. It means that, in our culture, it’s seen as normal for people to want romantic love, and to prioritise that kind of love over other kinds. (…) ‘Amato’ means romantic love and ‘normativity’ means what’s seen as culturally normal,” explains Meg-John Barker, the queer author of “Rewriting the Rules,” a book that exhorts the need for building newer forms of communities.

Just like other normative belief systems, amatonormativity conditions and encourages us to live life according to a certain script. It excludes all other forms of intimacies from consideration and puts the onus of a successful life on finding a romantic connection and sustaining it. It gives rise to the ‘relationship escalator,’ – which says adults find ‘the One,’—their ideal all-in-one romantic partner—marry them, have children with them, and stay together in a cocoon of happily-ever-after.

Amatonormativity is at work when romantic partnerships can make social benefits accessible to couples. Governments across the world have policies in place to make life easier for married couples. “Couple privilege” can bring anything from a couples’ discount to legal and medical benefits to couples.

The biggest fallout of this narrative is ‘that until you are not coupled you are incomplete.’ Ascribing to this can cause a lot of self-doubt, and self-worth issues. It gives rise to the negative stereotypes around singlehood while negating the value of the communities that differ from the prescriptions of amatonormativity.

Mainstream culture promotes the idea of a ‘relationship hierarchy‘

Armed with this new filter of understanding, everywhere I look I can find the subliminal messaging that props up amatonormativity as an attractive lifestyle. Take the classic romantic comedy When Harry Met Sally… (1989)—more like when heteronormativity met amatonormativity—that popularised the idea that a man and woman can never be friends, because they will inevitably succumb to the sexual tension and ‘consummate their friendship.’ It is easy to spot the underlying belief here, that a long-term heterosexual friendship should ideally precipitate into a life-long romantic commitment.

A decade later, our very own Karan Johar appropriated this idea for the Hindi mainstream audience. With his iconic debut, Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998), an entire generation of friendship-band brandishing people (read: also me!) grew up internalising the message ‘pyar dosti hai.’

It cemented the bias in us that ‘dosti,’ (platonic intimacy) that upgrades into ‘pyar’ (romantic and/or sexual intimacy) is greater than ‘dosti,’ which is simply ‘dosti.’ That friendships don’t count for much unless they blossom into a Mills and Boon-style romance.

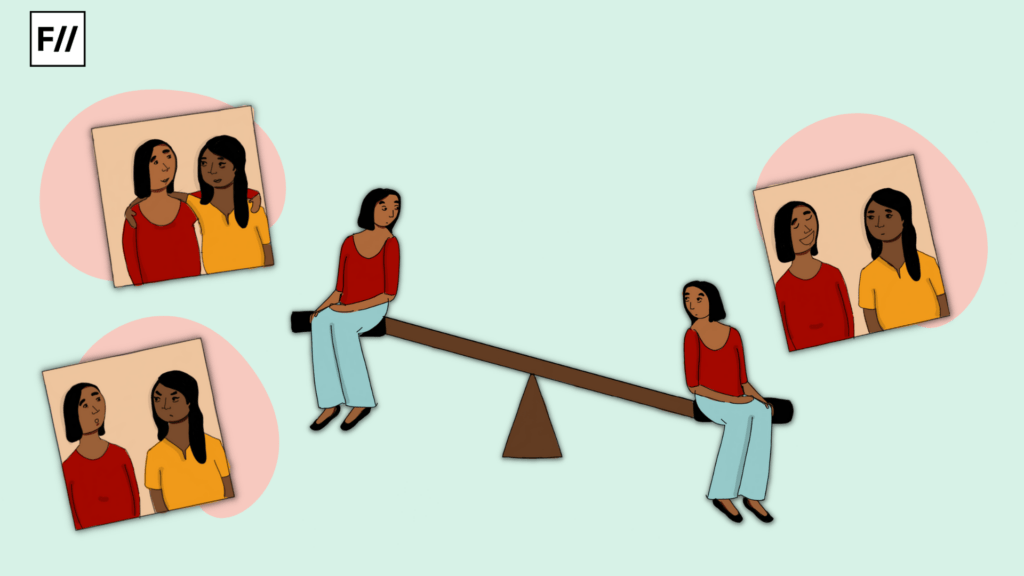

This further ingrained in us the notion of a ‘relationship hierarchy,’ that places romantic and or sexual partnerships higher than all other forms of relationships. Conversely, it fanned the fires of ‘incel culture,’ where men cribbed about being “friend zoned,” by women.

How amatonormativity stifles our desire for queer intimacies

I came across the possibility of ‘queer platonic intimacies,’ rather late in my life. If there ever was a phrase that acknowledged my experience of intimacy, then this was it. Since my school days, I was that child the teacher had to separately sit from their friends’ groups because together our exuberance was too hard to contain. My friendships were sacred sacraments, ‘ride or die,’ was my modus operandi.

Growing up, I wrote tender letters to my friends, moved cities because of my best friend, and had the deepest heartbreaks when friendships ended. I started feeling discontent with the moniker of ‘best friend,’ because the current cultural script couldn’t possibly encapsulate the richness of feeling I felt for my ‘best friends.’

As we moulted into the hormonal years of adolescence, most of my friends found it necessary to find a boy/girlfriend. Many a time, my friends didn’t reciprocate my fervour. Valentine’s Day frenzy eclipsed Friendship’s Day. Unable to compete with the heady passion of romance, my friendship was systemically reduced to the third wheel.

Under this systemic onslaught, my capacity for queer intimacies atrophied. It was replaced with a burning need to find a romantic partner, who would also moonlight as my best friend.

Unlearning the myth of ‘pyar dosti hai,’

It took my thirties for me to reach out and find my queer tribe to realise there was nothing wrong with me in the first place. I wasn’t a late bloomer to having intimate partnerships, I was making connections alright, just not according to the amatonormative script.

While I am no longer single, I am deliberately trying to unlearn the ‘relationship hierarchy,’ in my own life. I make a conscious effort to remember that my partner is not here to replace or minimise my friendships, and to unlearn the belief that only one great relationship is meant to fulfil all my needs.

It took my thirties for me to reach out and find my queer tribe to realise there was nothing wrong with me in the first place. I wasn’t a late bloomer to having intimate partnerships, I was making connections alright, just not according to the amatonormative script.

While dude-bros lament being ‘friend-zoned,’ I would take being zoned as a friend any day over having none. I pride myself in watering my friendships with the deepest tenderness. Because friendships in turn affirm the most vulnerable parts of me. But mostly because, in my pre-queer-awakening era, it was my friendships that afforded me the space to be my queerest self.

My queer friendships have and continue to support me and my needs as a neurodivergent person. As I have been talking to more queer folks, I have found more people like me, who have experienced deep intimacies within friendships. Armed with this new widening of horizons I quiver with hope at the prospect of building queer intimacies with people who think and love like me. I would like to go a step further and rephrase (if I may dare!) Vaid Menon’s beautiful line,

I want a world where friendship is appreciated for what it is!