In the bustling labyrinth of our urban landscapes, can there truly exist a feminist city? In our rapidly changing world, the concept of a feminist city is gaining momentum. The idea challenges conventional urban planning and questions whether our cities can truly embody feminist principles. Can a city be designed in a way that empowers and respects the rights and needs of all its inhabitants, regardless of gender? It’s a question that challenges the very foundations of how we perceive and construct our cities.

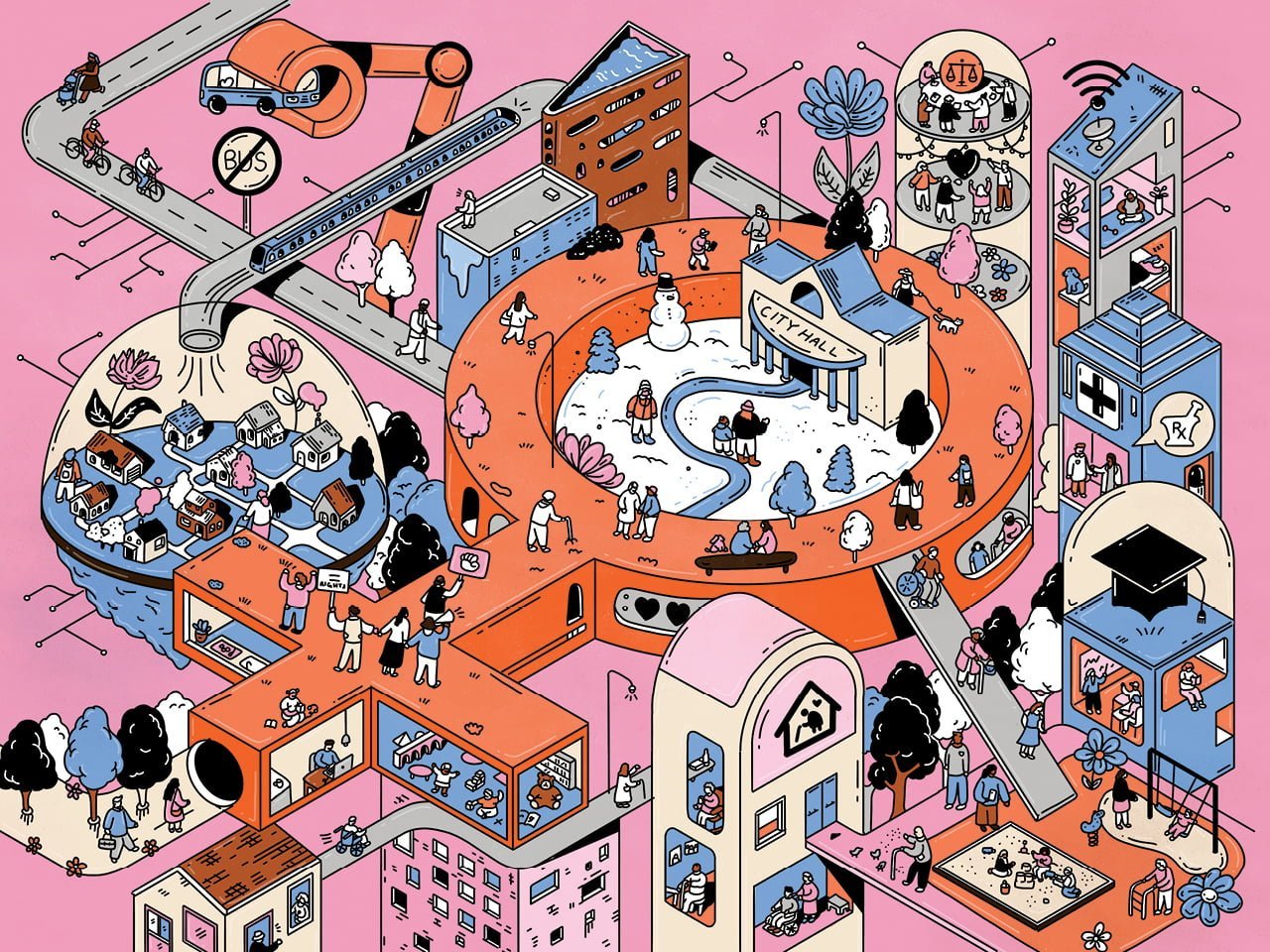

First and foremost, it is essential to acknowledge that cities, despite their concrete structures, are living entities. They evolve and adapt, influenced by the people who inhabit and navigate them. In this context, a feminist city would prioritise inclusivity, safety, and equality for everyone, irrespective of their gender or identity. The first cornerstone is safety. In a feminist city, the night does not shroud the streets in darkness and fear. It’s a place where women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and the marginalised walk freely without the heavy cloak of apprehension. Well-lit streets, readily available public transportation, and community patrols make safety an inherent right rather than a privilege.

One of the key concepts in understanding a feminist city is the “flâneuse.” Coined as a counterpart to the male “flâneur” by French writer Charles Baudelaire, the flâneuse represents a woman who strolls through the city, observing, and engaging with her surroundings. Historically, cities were often viewed as masculine spaces, designed to cater to the needs and preferences of men. The flâneuse challenges this notion by highlighting the importance of women’s perspectives in shaping urban landscapes. The flâneuse perspective emphasises the idea that a city is not just a physical entity but also a cultural and emotional one. Wandering the city streets without a purpose, the “flâneuse” is the embodiment of feminine urban exploration. She is the antithesis of Baudelaire’s male “flâneur,” whose very existence seemed to shape the city. Instead, she walks with intention, observing, interacting, and laying claim to the metropolis in her own unique way.

In “Bodies in Alliance and the Politics of the Street,” Judith Butler envisions a feminist streetscape as a space of profound transformation and resistance. She articulates the idea that streets can transcend their mere physicality and become vibrant sites of feminist activism and solidarity. In this vision, streets cease to be passive conduits for traffic but instead evolve into dynamic stages for social and political change. Butler explores how marginalised bodies, particularly those of women and gender-nonconforming individuals, can converge on the streets to collectively challenge patriarchal norms and oppressive power structures. It’s within this feminist streetscape that individuals can perform acts of public protest, demand recognition of their rights, and assert their presence without fear of erasure or violence. In doing so, Butler emphasises the crucial role of public spaces and streets in the ongoing struggle for gender equality and social justice.

In her book Feminist City: Claiming Space in a World Shaped by Men, Leslie Kern, an urban feminist geographer, explores the concrete manifestations of inequalities and oppressive systems within urban environments.

In her book Feminist City: Claiming Space in a World Shaped by Men, Leslie Kern, an urban feminist geographer, explores the concrete manifestations of inequalities and oppressive systems within urban environments. In the 1970s and 1980s, particularly in North America, cooperative housing developments emerged as integral components of feminist urban planning endeavours. These housing projects were centred around addressing the collective needs of lower-income communities, offering shared spaces for cooking, household chores, and childcare. Kern contends that these initiatives held great potential as alternative urban feminist responses to housing challenges. Regrettably, as Kern also acknowledges, these solutions proved short-lived, swiftly supplanted by neoliberal housing models that relied on the uncompensated labour of others and the capacity to afford premium facilities and services, especially in the realms of caregiving and cleaning.

Kern highlights how gentrification often plays a multifaceted role in the struggle for gender equality. On one hand, it can contribute to the creation of safer and more inclusive urban environments by bringing in new businesses, services, and cultural spaces that cater to diverse needs and preferences. However, it is crucial to scrutinise the less positive aspects. Gentrification can also displace marginalised communities, disproportionately affecting women, particularly women of colour. Rising property values and rent can force vulnerable populations out of their homes and neighbourhoods, disrupting their social networks and support systems. Kern’s work reminds us that achieving a truly feminist city requires a careful balancing act, where urban development respects the rights and needs of all, particularly those who have historically been marginalised and pushed to the periphery.

In the context of Sara Ahmed’s “Queer Phenomenology,” the imagination of a queer city or queer street entails a reconfiguration of urban spaces that challenge normative and heteronormative structures. A queer city or street is not defined by a specific physical layout but rather by the way it disrupts and deconstructs traditional spatial hierarchies and expectations.

In a realistic imagination of a queer city or street, one might envision spaces that prioritise inclusivity and diversity, welcoming individuals of all sexual orientations, gender identities, and backgrounds

In a realistic imagination of a queer city or street, one might envision spaces that prioritise inclusivity and diversity, welcoming individuals of all sexual orientations, gender identities, and backgrounds. A queer city will have physical infrastructure that challenges the binary divisions of public restrooms, for instance, providing gender-neutral facilities that are accessible to all. Not only the bare minimum, but it will have spaces that encourage the visibility of queer identities through public art, symbols, or events, challenging the notion that queerness should be hidden or confined to specific areas. Public squares, parks, cafes, and community centres are designed to foster a sense of belonging and encourage social interaction among queer residents and allies.

A feminist and queer city will serve as a hub for political activism and protest, where issues related to women empowerment and LGBTQ+ rights, as well as broader social justice concerns, are advocated for and discussed openly. Residents, planners, and policymakers will engage in ongoing dialogue to adapt and improve the city or street’s queer-friendliness, recognising that it is a dynamic and evolving concept.

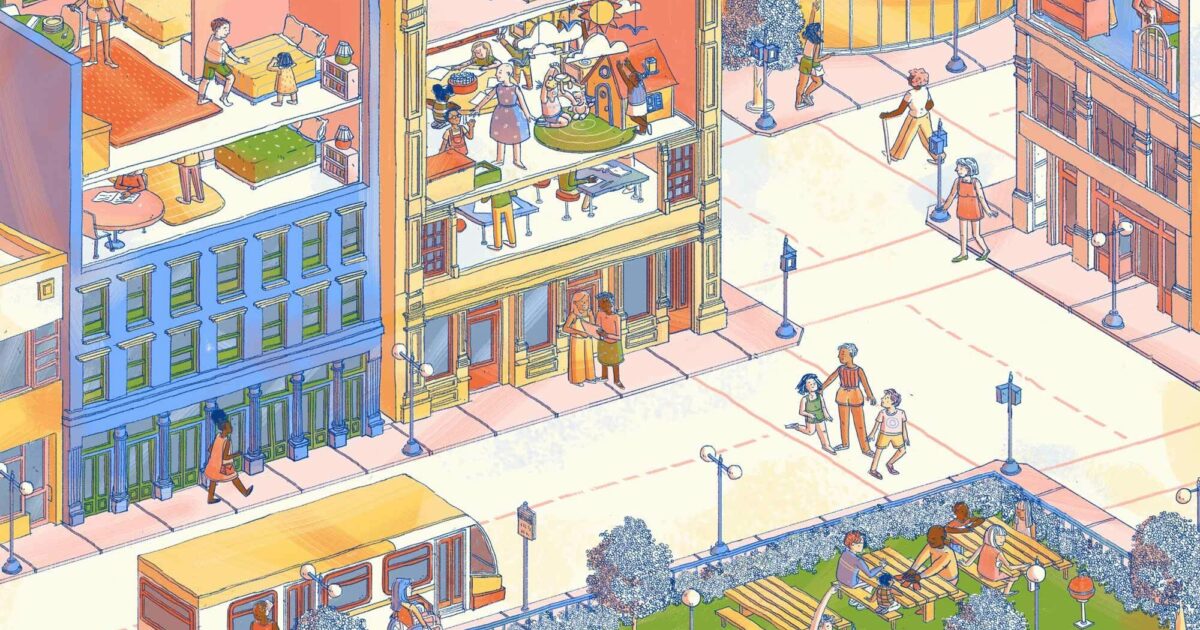

The concept of a feminist and queer city beckons us to dream of a more inclusive and equitable urban landscape. It challenges the status quo, encouraging us to reimagine our cities as places where equality, diversity, and justice are not abstract ideals but lived experiences. Through the eyes of the flâneuse, we see the city as a dynamic, evolving entity—As I strolled through the vibrant streets of this feminist city, I passed buildings wearing a kaleidoscope of colours, adorned with murals celebrating queer icons and feminist achievements.

Public art installations told stories of resilience and resistance, echoing the city’s commitment to honouring diverse narratives. On the sidewalks, I passed couples of all genders holding hands, embracing, and sharing smiles.

Public art installations told stories of resilience and resistance, echoing the city’s commitment to honouring diverse narratives. On the sidewalks, I passed couples of all genders holding hands, embracing, and sharing smiles. Rainbow flags billowed proudly from lamp posts, and women and queer-owned businesses thrived, their storefronts proclaiming their support for equality. As I continued my walk, I encountered a bustling community square, where a diverse group gathered for a feminist rally, their voices raised in unity against injustice. In this city, every step was an audacious stride of love, acceptance, and visibility.

About the author(s)

She/they is an editor and illustrator from the suburbs of Bengal. A student of literature and cinema, Sohini primarily looks at the world through the political lens of gender. They uprooted herself from their hometown to work for a livelihood, but has always returned to her roots for their most honest and intimate expressions. She finds it difficult to locate themself in the heteronormative matrix and self-admittedly continues to hang in limbo