The four-part series on Netflix would not need much introduction, as the world, not just digital, has been arrested by Philip Barantini’s “Adolescence” these past few weeks. Keir Starmer, the seated British Prime Minister, met the creators earlier this week. He backed Netflix’s decision to make the series available for free in UK schools. Not only that, UK schools are reportedly floating anti-misogyny lessons in their curriculum “following” the immense success of the series.

But this is not the UK’s first attempt at addressing the growing trouble on the feminist front. What seems to be the need of the hour? How did “Adolescence” manage to hit a chord so widely? Is gender sensitisation a concern for preteens?

Cultural impact of Adolescence: A wake-up call for schools

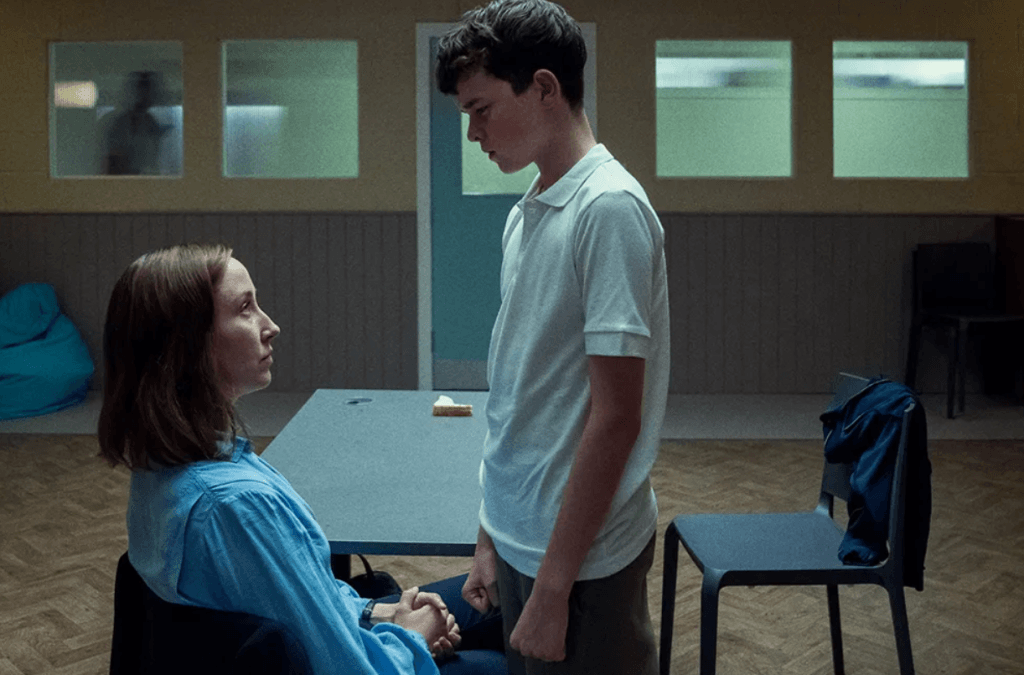

“Adolescence” tells the story of a 13-year-old perpetrator. Its greatest success is not in its single-take episodes (which is an incredible feat already) or the magnificent performance by a debut child actor but in its succinct portrayal of a crumbling school system. A child’s world largely belongs to that institution – its teachers and peers.

In the second episode, it becomes clear that the teachers are out of their depth, the students are lost in an unpredictable world of power plays and a large part of their upbringing belongs to the digital space that the adult world is largely disconnected from. A survey published by UNICEF says 1 in 8 girls experienced rape or sexual assault before the age of 18, globally. The same data is not so readily available for young boys. Sensitising at an early age is of utmost importance, not just to prepare them for the future but to combat their very vulnerable present. Navigating adolescence is a very difficult journey. They must be prepared with the correct information – not only regarding the physiological aspects of their journey but also the social and political experience of getting conditioned into one gender or another.

The UK had tabled a bill last year in an attempt to restrict youths’ unregulated access to the internet. It was eventually watered down for political benefit. It is important to talk about the world that is briefly touched upon in the series – the manosphere that adopts the vulnerable and lonely young minds lost in the identity of masculinity. In a recent address at Oxford, Slavoj Zizek spoke about the soft fascist state and the zeitgeist of shamelessness. Zizek’s philosophical treatise about the shamelessness of this current society is premised on the political acts and speeches that have been crossing the boundaries of propriety and due process. While this hypothesis deserves to be thoroughly investigated, it is evident that the general shamelessness allowed by relative anonymity online has also changed the way misogyny and patriarchy are showing up.

Unfortunately, that behaviour is not limited to the digital world and spills over to the real world, often as detrimental action. We also need to take a moment to process what the bill was proposing – urging social media companies “to exclude young teens from algorithms to make content less addictive for under-16s.” What kind of sense does this make? Do we think that an algorithm that is pushing harmful and addictive content to the rest of the world would not reach a younger audience? Do we not yet understand how prohibition works? Also, we shall willingly continue to poison the world with extremist and polarising algorithms but expect teenagers to grow up safe in the specially designed cocoon algorithm. This definitely sounds like a foolproof plan.

Digital manosphere and the rise of online misogyny

What makes “Adolescence” frustrating and possibly brilliant is when one pays attention to the periphery of the central story. From gendered behaviour and hierarchies to casual sexism and potentially criminal behaviour – throughout the series, the messaging from the adult world is in tandem with what the young ones are learning. From the detective to the counsellor to the mother – we see women gingerly managing and skirting aggressive masculinity and misogynistic behaviour.

While the adults appear shocked at discovering the world of the manosphere, it is remiss of them to not notice that the favourable conditions were created by the same generation and preceding generations for the misogynist vermin to grow. So, while we find ways to educate young humans about misogyny, it would be important to turn within and fix this abjectly patriarchal world in whatever little ways we can. The biggest failure of the series and, by extension, the world that watched it was its inability to acknowledge that gender is one of the most rigorous social integration processes and the upbringing of a young girl is not the same as that of a young boy. We do not empower them with the same facilities or allow them the same space to be precisely what they are – children.

Like most things on the internet, “Adolescence” has also divided the internet, albeit unequally. The dedicated citizens of the Manosphere are having a largely hormonal reaction, which is not the least bit surprising. The show’s creator, Philip Barantini, has also spoken about the backlash he has been facing online. But it is also kind of funny to see the other side of the reaction, adults heaving and hawing at the current state of affairs about adolescents as if the world we are introducing them to is not violently misogynistic. Both these reactions indicate that change can only be sown at the earliest age – before they have started accepting the gender dictums of the world.

But who will deliver such an education? Is an anti-misogyny curriculum the answer to teaching young boys how to “behave?” Or is it a feminist curriculum overhaul that would be the call of the hour? But who will bring it? The people in power – are they not casually and systematically sexist? Why is the question of masculinity structured around misogyny? Without one gender, will the other not exist? Then is the question not about gender more than misogyny or masculinity?

Does Adolescence fully address the crisis?

This is where “Adolescence” objectively fails to address the issue it had promised to. Baranteni chose four windows or perspectives to tell the story. The legal system, the school system, the perpetrator, and the parents. While the narrative works as a fantastic tool to get the attention of the three systems that decide the fate of a juvenile, it fails to tell the story of the protagonists at hand – the teenagers and their perspective. The beautifully rendered episode between the protagonist and the counsellor is an exemplary piece of television, technically. But it barely scratches the surface of the confusion, desperation, and vulnerability of the youth today – straddling physical and digital realities. By the end of four episodes, the narrative is unable to pull anyone out of the lonely stereotypes.

The victim’s narrative is watered down to the incel narrative, buried under the larger problem of share groups like our garden-variety Bois Locker Room. We only began to enter their world in the school but we are rudely pulled out from that and are unable to immerse ourselves in the reality of adolescence in the current age. In the last episode the show asked a crucial question and immediately failed to answer it – how did the daughter of the same family that the perpetrator hails from turn out completely differently? In a self-soothing answer, the parents tell each other that they used the same resources and approach, yet the boy turned out the way he did and the girl the way she did. It is a ridiculously essentialist approach that plays into the hands of the exact stereotype that gave way to the world of incels and other varieties of misogynists. The loneliness and isolation of young boys struggling with the idea of masculinity is the fertile ground for incel culture to grow roots. Gender is not a predisposition; it is a conditioning that one is rigorously processed through – from home to school to the internet.

The show is to be shown across schools and educational institutions for free in the UK, as ordained by the government. That is great news. A fantastic conversation starter. We hope the same will happen in India. But will it open space for young boys to truly and safely share what they are going through? Will it bring change in the peer interaction? If we pull focus back to the content at hand, does it truly represent the plight of growing up as a young boy in our society? Does it give space to understand them? Or does it only further the problem it locates – isolation, blaming, and stereotyping? (not necessarily in that order)

The UK had previously initiated a misogyny-sensitive curriculum. It is evidently a slow upkeep. The problem with our designs is that we fail to listen to the users or consumers of that design. What would an anti-misogyny curriculum look like? Another value education extra class? We all know how that went for us in school. Yes, we definitely need to sensitise them at an early age – for their own safety and for them to be better peers. But none of it will work if we do not step into their world and ask them what they need. We need to open the window that Baranteni’s work failed to – we need to listen and understand their plight in their language. It needs to be participatory and peer-focused – only then can we begin to design a curriculum that stands a chance in combatting the mess adults have created in their gendered world.

About the author(s)

She/they is an editor and illustrator from the suburbs of Bengal. A student of literature and cinema, Sohini primarily looks at the world through the political lens of gender. They uprooted herself from their hometown to work for a livelihood, but has always returned to her roots for their most honest and intimate expressions. She finds it difficult to locate themself in the heteronormative matrix and self-admittedly continues to hang in limbo