Trigger Warning: Rape

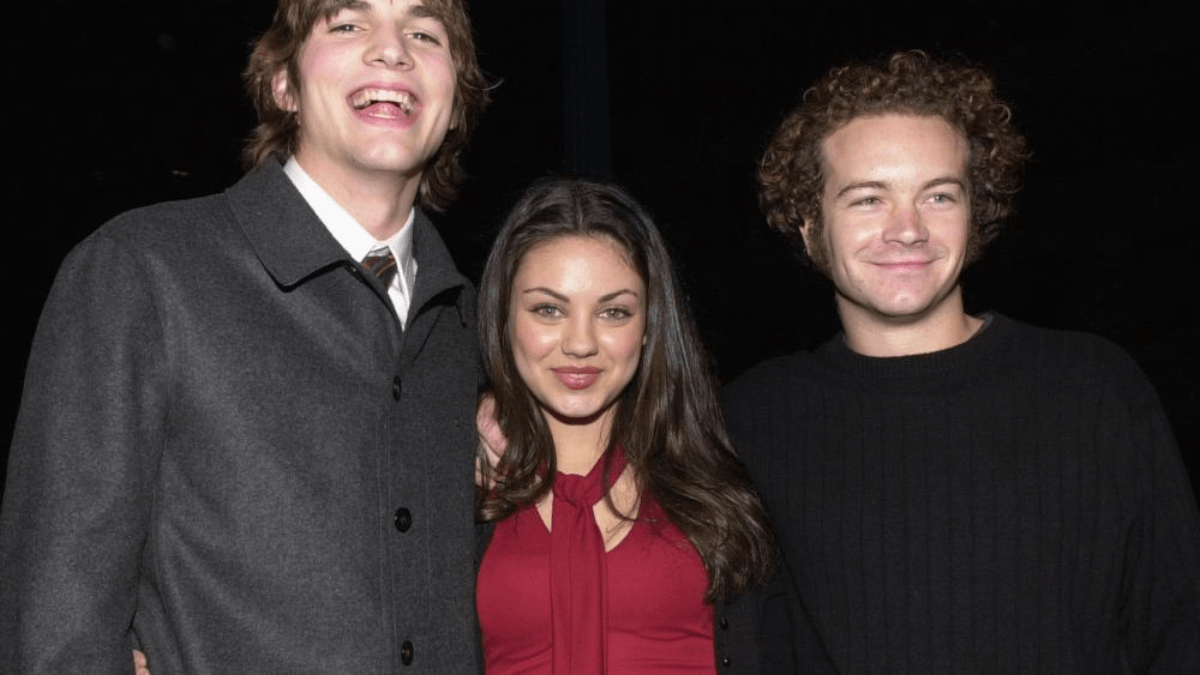

The furore over the recent public apology by Mila Kunis and Ashton Kutcher for writing character letters in defence of Danny Masterson convicted of rape, provokes a deeper analysis on why such an affair is of profound concern to feminist politics and ethics than what meets the eye. The conviction of Masterson this month came after years of legal battle that started in 2020 when the actor was charged with forcibly raping three women between 2001 and 2003.

The verdict that arrived in 2023 is an epilogue of sorts to the Hollywood’s #MeToo movement that globalised the discourse on sexual harassment and assault. Though the legal course of action taken up by the survivors has come to its fruition, the support that Masterson received from his friends, Ashton Kutcher and Mila Kunis among others, forces us to revisit the politics of MeToo, believability and complicity, thereby, raising questions for feminist politics and ethics.

The Kutcher-Kunis Controversy over the Masterson rape case

Danny Masterson starred in the beloved That 70s Show alongside Kutcher and Kunis. Years later, the Sitcom Star was accused of rape back in 2017 during the #MeToo wave. In 2023, Masterson was charged guilty of rape on two accounts sentenced to 30 years in prison. During the proceedings one of the survivors claimed that Masterson showed no sign of remorse, the other survivor stated in her statement that the ‘world is better off with you in prison.‘

In his defence, Masterson’s lawyer persuaded the judge suggesting that his life and that of his nine year-old daughter will be impacted by the decision that is made (Willimas, 2023). It was during the proceedings that Mila Kunis and Ashton Kutcher, well known for their roles as actors alongside Masterson in That 70s Show, in their leniency letter to the Court, wrote a character defence of Materson. The couple who have been friends with Masterson for over twenty five years ) wrote that he is an ‘exceptional role model and friend‘ and that he is a man who treated people ‘with decency, equality, and generosity‘.

Their letters were made public by the Hollywood Reporter. While this letter in itself is a problematic piece, the actors thought that to address it publicly would be a good move. They released a video on their instagram apologising for causing pain to the victims and that their letters were ‘meant only for the Judge to read‘ and was not intended to ‘undermine the testimony of the victims‘. Their response is suggestive of the ignorance under the garb of naivety and goodwill.

Kutcher and Kunis found themselves trapped in between their association with Masterson and their own consciousness of wanting to be on the “right side of history”

Kutcher and Kunis found themselves trapped in between their association with Masterson and their own consciousness of wanting to be on the “right side of history”. However, their continued friendship with an accused highlights the larger problem in the society- of hesitating to even consider believing the survivor and complicity in siding with the accused.

Why they cannot believe her “completely”?

Women who have accused men of harassment or rape are often never believed. The #MeToo movement made conversations around the topic more visible and acceptable. It lay bare the power hierarchies and structures that exist as everyday barriers to address violence let alone seek justice. It also raised questions on the credibility of these claims. However, the evidence for what happens inside a room/a closed space often at home and workplaces is almost impossible to verify.

The act of violating a woman’s body and her agency is grave but difficult to prove in the court of law and outside of it. The shame associated with acknowledging the very act of violation can be likened to death by a thousand cuts. The social stigma attached with rape, harassment add to the problem that a survivor might find themselves in- suspended between their own experience of pain and trauma and the negation of their experience by others.

The game of victim blaming robs the survivor of their own integrity and sanity. In the case of women who have been historically doubted, the over-exhausted tropes of “the crazy woman”, “the jealous one”, “she is misusing the law” and “she did it for revenge” trivialises the amount of pain and hurt forcing her to relive internalised shame and anger. A certain sense of permanent injustice prevails that sometimes cannot be addressed even in the court of law despite a favourable outcome.

The game of victim blaming robs the survivor of their own integrity and sanity

Though the MeToo Movement seemed to have erased some stigma surrounding sexual violence and gave women a voice to be heard and reckoned with, Banet-weiser and Higgins in their very interesting paper on economy of believability discuss that believability is not guaranteed to the survivor, rather needs to be performed that involves labour costs (Banet-Weiser & Higgins, 2022). Not all survivors might be able to bear the costs of this labour.

In the Masterson case, the survivors were discouraged from filing a complaint by the Church of Scientology to which the survivors and Masterson were affiliated with. Further, the fame that Masterson had, gave him the power, access and privilege to maintain his innocence regardless of the accusations. The letters by Kutcher and Kunis are an extension of this privilege- a testimony of the unwavering and uncritical support from Masterson’s friends despite his actions.

Complicity over collective responsibility in the Danny Masterson case

Further, a pertinent question emerges from this- the question of “complicity”. The backlash against Kunis and Kutcher stems from their belief that Masterson, despite his crime, is a “good person”. It raises ethical conundrums that feminist politics inevitably has to deal with: despite knowing the accusation of sexual assault does one’s continued affiliation to the accused make them complicit to the problem of believability and causes further injustice?

Should the relationship that one shares with the accused be enough proof of their innocence? Should persons close to the accused not hold them accountable for their actions? If proving harassment in the court or outside of it is difficult, should the lack of evidence be enough to disregard the unsettling thought of the possibility of the accused actually committing the crime? Should the survivor be given any benefit of doubt? Should we reduce experiences of harassment and trauma to mere binaries of “he said-she said” when historically women have not had the privilege of being believed?

Feminist politics and ethics cannot relinquish these concerns. The questions can be outsourced to legal agencies in matters of assault implying that the only form of true justice is the legal one; but is that not a convenient way out? It is therefore imperative to assess our commitment to the feminist ideal of creating safe spaces even within friendships and romantic relationships and compel ourselves and those around us to introspect inwards.

Should the relationship that one shares with the accused be enough proof of their innocence? Should persons close to the accused not hold them accountable for their actions?

One of the woman survivors in the Masterson case stated the following: ‘I lost everything. I lost my religion. I lost my ability to contact anyone I’d known or loved my entire life. I didn’t exist outside the Scientology world. I had to start my life all over at 29. It seemed the world I knew didn’t want me to live.‘ The very ontological threat that a survivor experiences- the isolation and constant judgement from their surroundings over their intentions and actions, the paranoia and persistence of anxiety that comes with being misunderstood and unheard provokes questions on how uncritical associations with an accused might further the moral injury that the survivor faces.

Should continuing any relationship with an accused be seen as an act of perpetrating greater injustice? What is striking, is the lack of conversations on empathy and the social-political collective responsibility of ensuring well-being of the survivor. How does one create a space, safe enough for survivors that keeps them from a self-imposed isolation and instead enables trust and mutuality?

Takeaways from the Danny Masterson case.

Though Masterson has been found guilty, he maintains his innocence. Kunis and Kutcher are taking the heat for their “character certification” of a convicted rapist. They are being held accountable for their actions but this is not the first time such uncritical support of an accused and consequently proven guilty has determined our role in ensuring greater (in)/justice.

The complicity in certifying the character of an accused invisibilises the complicity and no matter how unintended undermines the very personal experience of the trauma of a survivor. Truth has and will always be contested, its credibility questioned but as a society how certain are we of learning from our mistakes, addressing and acknowledging them? Feminist politics and discourse must embody practices of care, empathy and constant self-reflection that emphasises on the need for collective responsibility, accountability and promotes healing.

References

“Your sickness is no longer mine to bear”: The key moments from Danny Masterson’s sentencing. (2023, September 8). ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-09-08/danny-masterson-that-70s-show-rape-trial-scientology-prison/102830564

Nigar, S. (2023, August 10). “I believe her. I don’t know his story”: What being a “good” friend means in the era of #MeToo. Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/article/1053930/i-believe-her-i-dont-know-his-story-what-being-a-good-friend-means-in-the-era-of-metoo

Cho, W. (2023, September 8). After Danny Masterson Rape Conviction, “That ”70s Show’ Cast and Crew Asked Judge for Leniency. The Hollywood Reporter. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/ashton-kutcher-mila-kunis-letters-danny-masterson-judge-1235585997/

Banet-Weiser, S., & Higgins, K. C. (2022). Television and the “Honest” Woman: Mediating the Labor of Believability. Television & New Media, 23(2), 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/15274764211045742.