Whenever a man says ‘Women belong in the kitchen,’ I am reminded of my grandmother Didu, for whom the kitchen was her kingdom. Uprooted from her village of lush, green plenty in the district of Barishal in East Bengal (Bangladesh), during the Partition of India, the only thing she could bring back from that part of the world to keep and cherish were the recipes that her mother and other women around her had shared with her back home.

For Didu, the kitchen of our tiny South Calcutta flat was the only part of the house that had any importance and relevance in her daily life in an alien city. Even when, during her final days, her memories would play truant with her due to dementia, she would still be seen, stirring the cooking pot in our kitchen, following the recipes she brought back, the only things that she still remembered by heart.

In most refugee or immigrant Bangal households in South Calcutta, Didu’s story is ubiquitous. There is a mother or a grandmother who retraces her steps down a foggy memory lane through the myriad recipes she picked up in the old country, each with the distinct flavour, aroma and style reminiscent of a land they still insist on calling ‘house.’

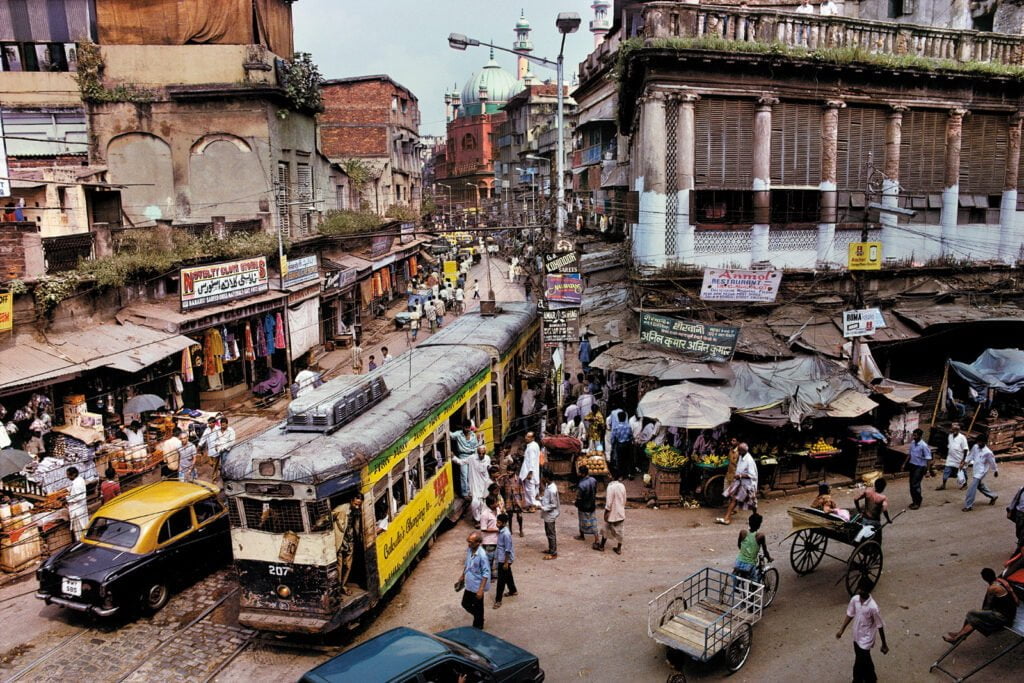

Food and cooking have played an important part in the lives of immigrant women in all cultures. The loss of the original ‘home,’ and the forced displacement to a big, alien city like Calcutta, during the Partition, led to a loss of identity and culture. Fleeing from the terror of the communal riots, people took shelter in makeshift houses. Dislocated and homeless, the refugees from Bangladesh set up tents under flyovers and on the pavements.

This disorientation and reorientation from home to a place that would have to be home became part and parcel of the life of most refugees who were forced to leave their homes and villages behind. Susan Fraiman in her essay on homemaking by the unsheltered posits a question– “Are the lives of displaced people ever the occasion for depicting a therapeutic domesticity?” (Fraiman 155). It is argued that there are certain cases where the answer is yes. She highlights the “cleverly rigged-up kitchens,” (Fraiman 156) of the New York “tunnel people,” as notable examples.

In the case of the refugees who travelled from Bangladesh to Kolkata in order to avoid the mass mob killings that were taking place, the food that provided them with a sense of home is closely connected to their disrupted identity.

The use of the kitchen as the primary space to explore domesticity has direct connotations with considering food to be the connecting link between the home left behind and the space of relocation. Sitting around the table and enjoying the food that the refugee used to have back home, however, is only a symbol of domesticity if the food available reminds the refugee of home.

In the case of the refugees who travelled from Bangladesh to Kolkata in order to avoid the mass mob killings that were taking place, the food that provided them with a sense of home is closely connected to their disrupted identity.

Since women are the ones who do most of the cooking in our culture, recipes take the shape of priceless family heirlooms to be passed down through the generations. Bengali refugee women, similarly, brought their recipes and culinary memories across the border, in place of the land and other tangible wealth that they could not bring back. Recipes, therefore, are transformed from just a set of cooking instructions to a valuable and intangible cultural heritage that provides displaced Bangal women with a sense of belonging and identity.

Perhaps the dishes have to be adapted and transformed to suit the ecological and economical constraints of a city like Calcutta where foraging wild shaak (leafy greens) or geri-googly (mussels and molluscs) is almost impossible and fresh ilish fish or hilsa costs an arm and a leg which is almost inaccessible to impoverished refugee families. Therefore, some adjustments are made to the recipes but the overall spicy and diverse flavour profile due to the liberal use of tel-jhaal-moshla (oil, heat and spices) remains the same.

The 2023 Bengali web series adaptation of Kallol Lahiri’s book Indubala Bhaater Hotel (Indubal’s pice hotel) directed by Debaloy Bhattacharya on the OTT platform Hoichoi, starring actress Subhasree as Indubala, the life and memories of a Bangal woman who marries into an abusive Ghoti (Bengalis who have always lived in West Bengal) household, is depicted with great nuance and is bound to strike a chord with Bangal women and refugee families.

Indubala’s journey from a little girl in rural Bangladesh to a newly married bride in Calcutta and ultimately to an entrepreneur, a woman owner and cook of a popular pice hotel, charts her relationship with food and the people around her. The storyline makes use of flashbacks and merges the past with the present, refusing to subscribe to the linear, masculinist idea of time and temporality. This feminine time is subversive, a nod to the disrupted and skewed temporalities of displaced people.

Indubala brings with her dishes and recipes from East Bengal, which are scoffed at by her promiscuous, violent and alcoholic husband as well as her orthodox, oppressive and hateful mother-in-law. Both son and mother mock Indubala for her identity as a Bangal woman who never actually ‘belongs,’ to their home in Calcutta. After the death of her husband and mother-in-law, Indubala raises her two sons on her own with the help of the local fishmonger Lachhmi and their loyal house help.

Perhaps, that sense of homelessness is shared by all refugee women from East Bengal. Known in Bengali parlance as chhinnamool (rootless), these women never really feel at home, even after their families have acquired some money to build their own homes in the city of Calcutta.

However, even at a ripe, old age, when she actually owns the house in Calcutta and runs her own business there, she never actually ‘belongs.’ Perhaps, that sense of homelessness is shared by all refugee women from East Bengal. Known in Bengali parlance as chhinnamool (rootless), these women never really feel at home, even after their families have acquired some money to build their own homes in the city of Calcutta.

Indubala Bhaater Hotel is an ode to the perseverance of refugee women from East Bengal. It is a homage to these women in the kitchen, making a meal out of their memories, tasting the trauma of displacement and forced migration and seeking, in vain, a sense of home in a plate of shorshe ilish.

David Bell and Gill Valentine in their book Consuming Geographies: We Are What We Eat link national identity to food, saying that “every mouthful, every meal, can tell us something about ourselves and our place in the world.”

According to them, “The history of any nation’s diet is the history of the nation itself….” Much like social anthropologist Arjun Appadurai who says that “food can be used to mark and create relations of equality, intimacy or solidarity or, instead, to uphold relations signalling rank, distance or segmentation.”

West and East Bengal – while sharing a common cuisine – exhibited marked differences in traditions, balanced on regional bounty and food habits. The erstwhile East Bengal was predominantly multi-cultural, stretching up to Assam at one end and down to Burma at the other, the culinary styles flowing freely in between and creating distinct identities.

By virtue of three major rivers flowing through it, the lush terrain yielded more than 100 different leafy greens and over 500 varieties of fish in the innumerable water bodies dotting the countryside. West Bengal, on the other hand, was just a small part of the vast canvas that was Undivided Bengal, geographically different with resources not as varied or abundant as those of the East.

As Arundhati Ray explains in an article titled “Food Prints of Partition,” “It’s the everyday nature of food that makes it so powerful in creating – and nurturing – a community’s identity. Kolkata’s familiar yet alien food was a daily reminder of their (the displaced) rootlessness. Here too, meals featured rice, dal, vegetables, and fish. But they yearned for what their palates were accustomed to…. For the humble greens (shaak) and small fish that Kolkata’s urbane markets did not deem worthy of stocking.”

After my grandmother’s death, food from ‘back home,’ rarely made an appearance on our plates. Sometimes, my mother tries her hand at recreating the recipes Didu left behind, but her renditions are conscious of heart problems and cholesterol and lack the generous tel-jhal-moshla that were so central to my grandmother’s cooking. Her recreations are milder, tame and meek almost, in comparison to Didu‘s bold original, bursting with life and vigour. This culture of recipes from what Didu called ‘home,’ taking a backseat in the daily platters of refugee Bengalis is a sad phenomenon which is all too real.

Since these recipes were mostly preserved orally and in the individual and collective memories of refugee women, and were rarely written down, there has been almost no documentation and archival work on these carriers of memory and identity.

Now, most first-generation Bangal refugee women have either passed away or are bedridden, unable to recount their recipes and share their knowledge. The lack of initiative to preserve female knowledge and the memories of displaced people as intangible cultural heritage points to the snobbish disregard towards subaltern and marginalised memory by academics, researchers and archivists. Due to this, barely any culinary memory from Bangal refugee women survives today.

However, memory has a strange way of persisting, through fictionalised narratives on OTT platforms like Indubala Bhaater Hotel or in sudden guest appearances at our lunch table when my mother decides to chuck the health consciousness out of the window for once and gets Didu’s recipes perfectly right (well, almost).

As long as narratives like Indubala Bhaater Hotel and the fond twice-removed memories of families like ours live on, we can taste the intangible heritage carried on the shoulders of refugee women across the border and perfected in the kitchen, one shorshe ilish or note shaak bhaja at a time.

References:

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1981. “Gastro-Politics in Hindu South Asia.” American Ethnologist 8 (3): 494-511.

- Fraiman, Susan. 2019. Extreme Domesticity: A View from the Margins. N.p.: Columbia University Press.

- Ray, Arundhati. 2017. “Food prints of partition.” Mint, August 11, 2017. https://www.livemint.com/Leisure/1z4gEjxaIVWTxcAe7XtEQK/Food-prints-of-partition.html.

- Valentine, Gill, and David Bell. 1997. Consuming Geographies: We are where We Eat. N.p.: Routledge.

About the author(s)

Ananya Ray has completed her Masters in English from Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India. A published poet, intersectional activist and academic author, she has a keen interest in gender, politics and Postcolonialism.