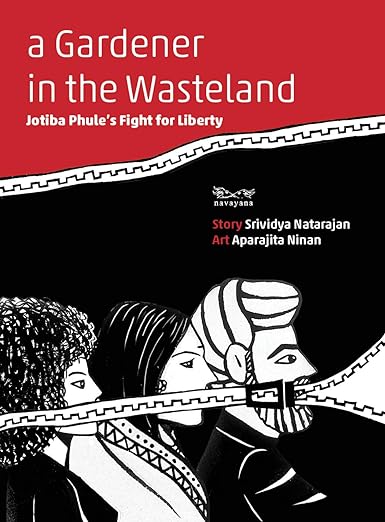

The most pervasive historical trauma in India, caste-based oppression and violence, found a home in graphic memoirs in 2011. A two-woman team—Srividya Natarajan as the author and Aparajita Ninan as the graphic artist—wrote and illustrated “A Gardener in the Wasteland: Jotiba’s Fight for Liberty.” In A Gardener in the Wasteland, Natarajan and Ninan are continuously seen in Delhi in 2010 as they explore, comprehend, discuss, and eventually share the world and ideas of Jotiba Phule and his wife and “business partner,” Savitribai.

Narratives by Non-Dalit

Beginning with Mulk Raj Anand’s Untouchable, published in the early 20th century, Indian fiction has made an effort to highlight the caste system’s historical oppression. This work has frequently been done by non-Dalits and, during the 2000s, by Dalit writers such as Bama and Sivakami. However, this is also a criticism of this book: writer and illustrator are themselves not from dalit backgrounds; hence, speaking on behalf of the oppressed population with privileged eyes might invoke the ones with the identity and might not be able to justify the long fight of representation.

The creators of these graphic texts are not even second-generation inheritors of what Marianne Hirsch termed “post-memory.” As a result, they are or must be, much more sensitive to concerns of exoticising or trivialising the atrocities of the past. However, graphic novelists cannot claim such “authenticity,” if it is thought that the issue of authentic experience continues to be at the forefront of considerations for all writers of novels, memoirs, or commentary about such events. However, these books offer a crucial connection between historical narratives and the comprehension of contemporary social movements.

Consequently, history, like myth, is subject to change based on who writes and who reads it, as Ninan proclaims in A Gardener In The Wasteland. Especially since there isn’t a deux ex machina in the real social domain that would come to save humanity from codified exploitation, but rather a regular crusader calling for upliftment through education, Jotiba wrote and spoke in order to shock, to make people do more than listen idly to a mild voice of reason.

After a quick examination of the Phules’ life and career narrative, A Gardener in the Wasteland provides a historically grounded critical portrayal of caste exploitation in India, while also reflecting on many forms of prejudice and oppression that afflict the country’s social and cultural structures.

Storytelling and references

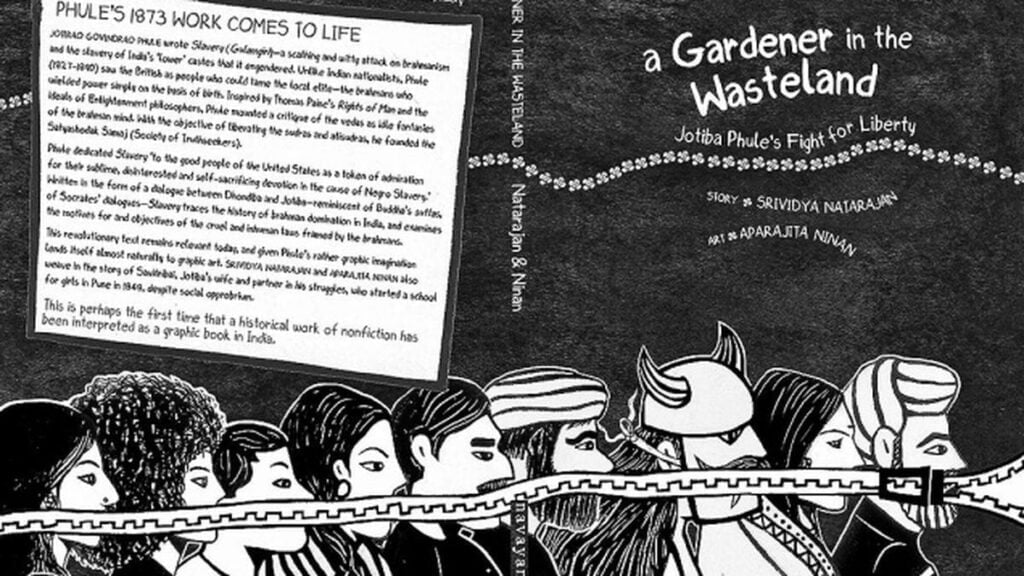

The entire A Gardener In The Wasteland is based on Gulamgiri and offers examples of Phule’s criticisms of Brahmin accounts of Indian mythology and history. Phule continued to break the myth in a satirical way, which also provided a good laugh. One hundred thirty-three years before Richard Dawkins started his frontal assault on the concept of god in his 2006 book ‘The God Delusion,’ Jotirao Govindrao Phule declared war on a religious system that glorified one class of people while stomping on those considered inferior. Gulamgiri (Slavery), Phule’s 1873 publication, was a scathing attack on Brahmanism and Hinduism in which he not only attacked the codified exploitation of the ‘sudras‘ and ‘ati shudras‘, but also called for the uplift of India’s ‘lowered castes,’ through education and by aligning their cause with the British.

Natarajan and Ninan compel us to confront the brutality, injustice, bloodshed, and overbearing control that caste still exercises over millions of people in India. Phule reiterates what the Manusmriti actually depicts in relation to sudras and the Vedas, in a powerful double spread. Conversely, the writer-artist team effectively draws a parallel between the harshness of caste system and the poetry “Strange Fruit” by Abel Meeropol, which was immortalised by Billie Holiday in her song about black lynchings and American racism.

More powerfully than any other argument regarding racism and casteism being kissing cousins, is the picture of a cloaked Ku Klux Klansman eating the peculiar fruit of prasada with a portly Brahmin priest. A news article on “nine dalit children among 15 rescued from bondage in Tamil Nadu,” appears as we turn the page. This is not the Pune of Phule’s 19th century, but India in April of 2010. The black-inked characters translate the popular tales by Brahmins to its real connotation, leaving strong impressions on the reader’s head.

A Gardener In The Wasteland has a strong sense of a story within a story as all of the major characters—from Phule to his buddy Dhondiba, via Natarajan and Ninan—discuss a variety of myths, historical events, and modern-day happenings that have shaped India’s present understanding of caste. The attempt to contextualise the caste struggle across temporal and spatial dimensions is commendable; yet, it has been sacrificed in favour of a more coherent narrative that could have been enhanced by concentrating more on Phule’s story and its immediate setting.

Commentary inside a commentary

The graphic novel is narrated in a self-reflexive style. The first panel shows the writer and artist strolling through Delhi’s streets as they discuss the roughs for the book and the script, while an elderly man yells caste-based obscenities at kids playing ball in his backyard. The tone of the rest of the text is foretold by this technique of commentary inside a commentary.

By using this approach, Natarajan and Ninan are able to put caste and oppression in the perspective of global efforts for equality, including the American Civil Rights Movement and the French Revolution, while maintaining a certain distance from their own work. Newspaper clippings detailing caste-based crimes in modern India are mixed with images from Manusmriti’s description of the primordial beginnings of the cosmos.

Characters practically leap from the pages of history to debate with Phule, with Savitribai gently pointing out their points of contention for the uninitiated reader. This book also serves as a powerful argument of Phule’s radical humanism and his revolutionary attitude as a rationalist who is fighting against organised religion’s obscurantism.

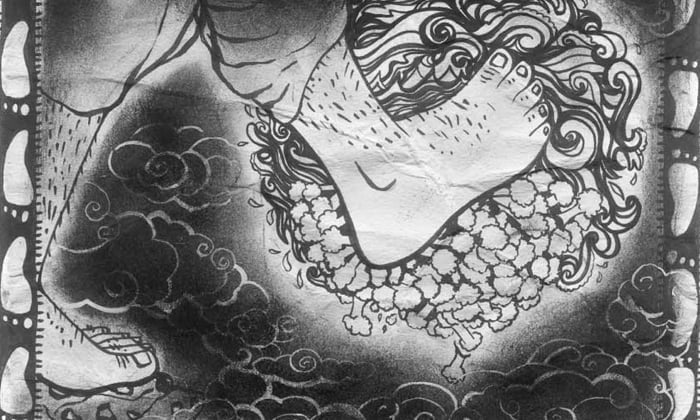

Phule presents his “Aryan-centric,” mythology as a counterargument to the Vedic accounts of early Indian history. One by one, Phule dissects each of the ten avatars of Vishnu, highlighting how these were exalted representations of early invaders who were given “divine” attributions for political purposes, the main one being to maintain the subjugation of India’s native inhabitants (shown as asuras, under the control of the brahman-usurpers, shown as devas).

According to Phule in Gulamgiri, who is quoted in one speech bubble: “Since Brahma had vaginas in four places—mouth, groyne, arms, and legs (since the four varnas were born out of these four parts), each of them must have menstruated for at least four days each, and he must have sat in seclusion, as an unclean person, for sixteen days each month. Then who did the chores?” The reason this counterargument seems funny (or obscene) is that Phule is refuting arguments with the same absurd reasoning that the brahman employs.

Producing “the other“

This graphic novel revives Phule’s iconic—and iconoclastic—work while continually reminding the reader how it remains such a cogent, palpable, living text even in 21st-century India, a “sovereign socialist secular democratic republic.” This is what makes A Gardener In The Wasteland so exceptional among the many publications on India’s political and social histories. However, Ninan and Natarajan create a caricature of “the other“—a fat, elderly priest who is seen marching across the pages of the book, carelessly committing atrocities in passing and leaving a path of destruction in his wake, complete with the caste thread, tilak, and tuft of hair symbolising the corrupt, morally devoid Brahmin.

After decades of land, history, and culture being taken from the lowered castes, dehumanising the other may sound like poetic retribution, but it seldom accomplishes anything. The result of the book’s polarisation and preaching to the converted is that it loses a valuable chance to interact with readers who would otherwise have been persuaded by the promise of graphic art with an Indian subject but are instead turned off.