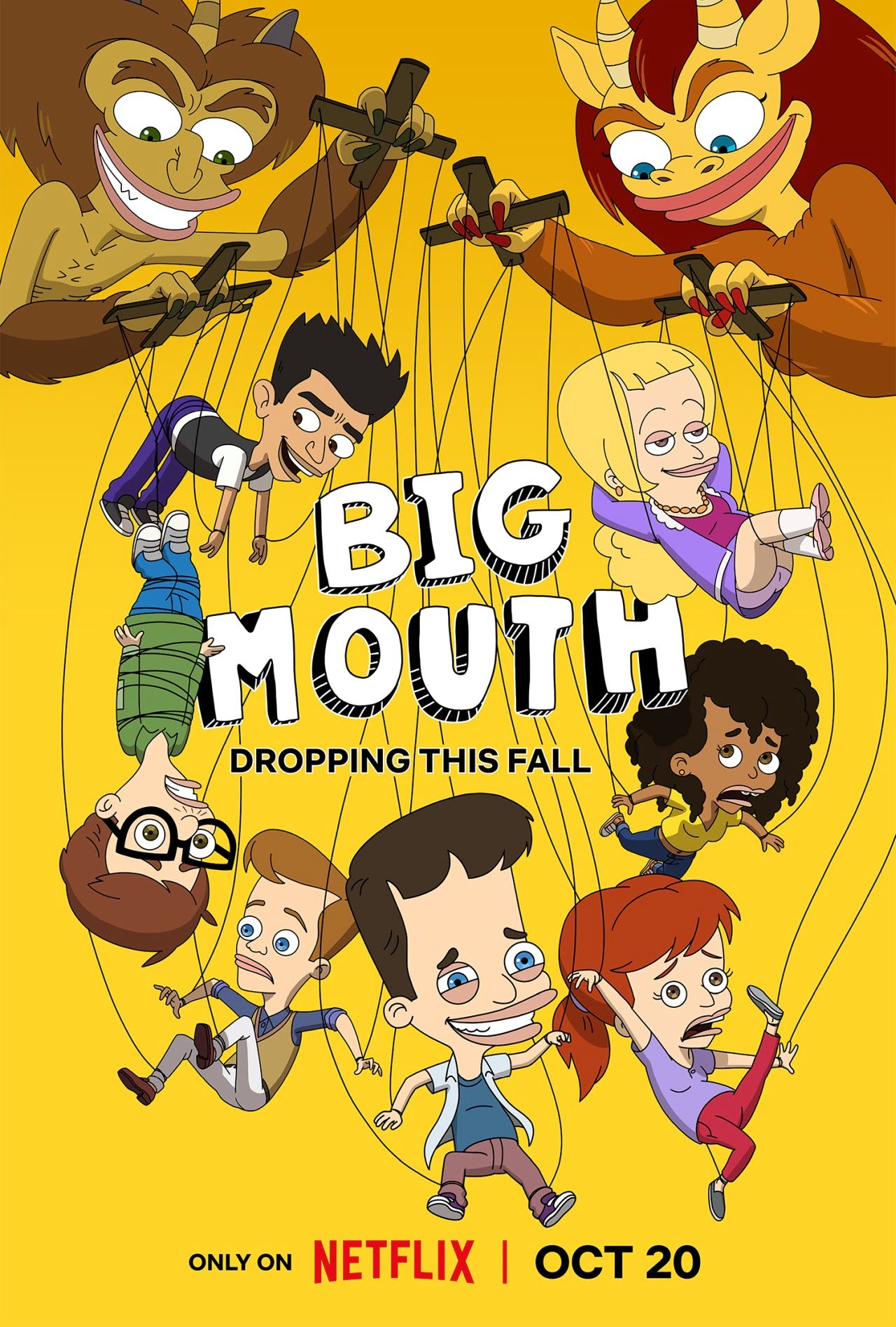

Big Mouth, an animated series created by Nick Kroll, Andrew Goldberg, Mark Levin, and Jennifer Flackett, delves into the awkward, confusing and often hilarious world of puberty. While the show is celebrated for its portrayal of adolescence and handling themes of gender, sexuality, and empowerment – the question is, does it perform under the feminist lens?

Big Mouth admirably breaks the silence surrounding puberty, offering a candid exploration of the physical and emotional changes experienced by both boys and girls.

Big Mouth admirably breaks the silence surrounding puberty, offering a candid exploration of the physical and emotional changes experienced by both boys and girls. The show deserves praise for its commitment to demystifying this universal experience by depicting menstruation, masturbation and hormonal fluctuations openly. The effort to normalise these topics and dismantle the stigma associated with them is evident in the writing. But the shocking writing of the show makes it an ironic misfit for children.

Big Mouth: from smashing gender roles to celebrating bodies and sexuality

One of the strengths of Big Mouth lies in its dedicated attempt to challenge gender stereotypes. The characters are multidimensional and defy traditional gender norms. The female characters are not relegated to passive roles; instead, they navigate puberty with agency, confronting societal expectations head-on. Big Mouth promotes the idea that girls, just like boys, can be complex individuals with varied interests and experiences. While they address the binary issues of the heteronormative world the show fares well in trans and non-binary representation, even though they get the spotlight only for a few minutes.

Big Mouth emphasises the importance of consent and communication in relationships. It is really intelligent to disembody some of the conversations through the rambunctious voices of the famous hormone monsters. The show does not shy away from portraying the awkwardness and vulnerability that accompany sexual exploration during adolescence. It underscores the significance of mutual understanding and respect, fostering a narrative that promotes healthy relationships and emphasises consent as a fundamental aspect of intimacy.

Maya Rudolph’s explicit ode to boobs, butts, and body shapes in the Season 2 is one of the earliest and strongest positive steps by the show toward body image. The song ‘Every tushy is a snowflake, every nipple is a star!‘ is an embodiment of the show’s intention as it goes on to depict characters with diverse body types and sizes. The show encourages viewers to embrace their bodies and recognise that there is no one-size-fits-all definition of beauty. This inclusivity is empowering, as it challenges harmful beauty standards and fosters a more accepting environment for individuals to appreciate their bodies during a time of intense physical change. Not to forget the fantastic episode on menstruation – the role of period in the pubescent menstruator’s life. Jessi throat-punching Jay when he asks her if she is on her period because she looked angry, was one of the most educational moments of the show!

Big Mouth: from MeToo to masculinity

The show’s leading pair might be a pair of teenage boys but it majorly stands on the shoulders of strong, supportive female friendships. The female characters in the series navigate puberty together, facing challenges with a sense of solidarity. By showcasing the power of friendship among girls, the show dismantles the trope of female rivalry and underscores the importance of mutual support. There needs to be special focus on Missy’s stuffed worm – the easy conversation about masturbation and orgasm irrespective of gender is a breath of fresh air. Rarely do we see such candid and genuine attempts to showcase young girls exploring their own bodies and falling in love with masturbation.

The hormone monster Connie’s unawareness of social norms and gender roles reflects the impact of socialisation on individuals’ views of gender traits. Her past experience mentoring girls leads her to perceive crying as normative gender behaviour, revealing a lack of awareness when Nick’s emotional vulnerability is considered differently. The series positively depicts Nick’s deviation from traditional Western masculinity, endorsing his sensitive expression. Nick’s older sister supports this shift, signalling a changing narrative around masculinity. In contrast, the portrayal of Andrew embodies toxic masculinity, contrasting with the acceptance of Nick’s sensitive masculinity.

The series reflects on toxic masculinity through characters like Nick and Connie, highlighting the fluidity of hegemonic masculinity and suggesting a potential shift to previously marginalised forms. Elliot, Nick’s dad, exemplifies nuanced masculinity, challenging conventional gender norms with both stereotypically masculine and feminine behaviours.

In a post-MeToo world, the series successfully becomes the sensitive supporter of the movement

In a post-MeToo world, the series successfully becomes the sensitive supporter of the movement. The Disclosure musical, protested by the students, is a fantastic example of the show’s continued focus on feminist narratives. The plight of Bridgeton Middle School’s female students reaches its apex during the school musical, Disclosure the Movie: The Musical, an adaptation of a 1994 film featuring Michael Douglas falsely accused of sexual harassment by Demi Moore. The opening number, featuring an animatronic boss exclaiming, ‘Beware! Pretty women want our jobs!‘ sets the tone.

Despite Jessi’s condemnation of the musical as a “misogynistic fantasy”, Lizer takes a #MeToo critic stance, portraying it as an exploration of challenging times for men. The girls, paging through the script, discover offensive roles like Jessi as the “Dutiful Wife” and Gina as the “Senorita Cleaning Lady.” When confronted, Lizer dismisses their concerns with a mere ‘Because, diversity.’ The girls, refusing to play along, quit the musical, while Missy, taking the lead role, pledges to bring change from within (we have all been there). Jessi’s criticism and shaming of Missy’s decision highlights the complexities of girls policing each other’s feminism (again, we have all been there).

The conversation about toxic masculinity is also well-portrayed. Andrew embodies the emotionally unintelligent young men of our times who vociferously try to stay on the path of wokeness but remain lonely due to their incapacity to be vulnerable. It is an important peek into the making of an incel. The exploration of masculinities in Big Mouth delves prominently into the character of Nick and his relationship with his father, Elliot. In the third series, Nick grapples with the complexities of adolescence under the guidance of his new female hormone monster, Connie. His unease about having a female mentor stems from the societal expectations tied to masculinity. Nick’s conversation with his friends reveals a poignant concern about how having a female hormone monster might challenge his perceived masculinity.

While the series aims to normalise discussions around sexuality, some aspects of Big Mouth contribute to a problematic narrative.

This moment reflects the vulnerability-cost dynamic in male identity, echoing Connell’s concept of hegemonic masculinity, where any deviation from traditional norms risks questioning one’s legitimacy in the patriarchal hierarchy. Nick’s apprehension and subsequent discussion with his friends mirror Mead’s notion of ‘the generalised other,’ highlighting the scrutiny individuals face in aligning with gender role expectations. The ongoing learning experience between Nick and Connie exposes normative gender roles, as seen when Nick’s emotional vulnerability is met with mockery from his male peers, reinforcing the stereotypes associated with masculinity. There can be no feminist reading of the show without mentioning Coach Steve – from celebrating friend-zone to being the embodiment of adults with unhealed childhood trauma. The only wish is for the show to have been softer with the character and added more nuance to the humour attempted in the writing of his character.

The politics and problematics of depictions of sexuality in Big Mouth

While the series aims to normalise discussions around sexuality, some aspects of Big Mouth contribute to a problematic narrative. The use of anthropomorphised Hormone Monsters, particularly in relation to female characters, can be seen as objectifying and reductionist. The representation of female sexuality often leans towards sensationalism rather than genuine exploration, risking the reinforcement of harmful stereotypes. Even queer representations continue to be skin-deep as Matthew is the only recurring character consistent through seasons who is queer. The conversation about Jake is another one to be had, another day. The hormone monster is a progressive and somewhat endearing mess that really misses the mark when Andrew’s hormone monster Maury seems to engage in what can only be defined as necrophilia.

In a series brimming with notable moments, Jessi’s impassioned conversation with Nick stands out as the most powerful. Venting her frustration about the challenges of being a girl she charges at Nick who is genuinely perplexed:

Jessi: You don’t get it. You don’t know what it’s like being a girl. People tell you what to wear, the whole world is telling you how big your boobs should be, and you called us sluts!

Nick: I’m on your side. I just literally don’t know what to do.

Jessi: I don’t know exactly either. I think it might just be this long conversation that we all have to keep having.

The show through the voices of these nubile actors acknowledges the complexity of the matter, emphasising the necessity of an ongoing conversation. This dialogue encapsulates the heart of Big Mouth, which boldly delves into the continual negotiation of gender and sexuality. The show distinguishes itself as a remarkable exploration that neither moralises nor condemns but intimately examines the agony and ecstasy of this vital, never-ending conversation. Big Mouth navigates both the internal struggles of defining one’s sexuality and sexual politics and the external efforts to empathise with others’ challenges.

While other shows, such as Bojack Horseman and Jane the Virgin, tackle similar subjects in adult contexts, Big Mouth uniquely reverses the narrative, portraying children dealing with these complex issues

While other shows, such as Bojack Horseman and Jane the Virgin, tackle similar subjects in adult contexts, Big Mouth uniquely reverses the narrative, portraying children dealing with these complex issues. In contrast to adults grappling with morality, the middle schoolers of Bridgeton Middle School navigate their nascent identities, sexualities, and moral compasses with fewer tools and less clarity. Big Mouth grants them the space to make mistakes and evolve while avoiding the pitfalls of becoming overly didactic. In these special episodes, Big Mouth adeptly addresses grown-up problems through the lens of cartoon tweens, showcasing a nuanced understanding of complex issues. As Big Mouth continues to break new ground in its portrayal of gender, it not only entertains but also contributes to the ongoing feminist conversation.

About the author(s)

She/they is an editor and illustrator from the suburbs of Bengal. A student of literature and cinema, Sohini primarily looks at the world through the political lens of gender. They uprooted herself from their hometown to work for a livelihood, but has always returned to her roots for their most honest and intimate expressions. She finds it difficult to locate themself in the heteronormative matrix and self-admittedly continues to hang in limbo