Underneath the catchy beats and groovy rhythms, Punjabi music gives us a glimpse into the complex web of societal issues including sexism and casteism. Over time, Punjabi music has undergone a transformation from its origins in poetic love ballads such as Heer Ranjha and Mirza Sahiba, as well as other traditional folk music forms, to the contemporary Punjabi Pop era which is currently making noise in the regional as well as international space.

Stuart Hall’s assertion that ‘every regime of representation is a regime of power’ holds weight when examining the dynamics within Punjabi music (Hall, 1990). The industry serves as a tool reinforcing power structures, notably within the historically influential Caste-Jatt Sikh community. The historical association of Jats with power and privilege, particularly due to their role in the British colonial army, solidified their identity as a martial caste, bolstering hypermasculine values linked to physical strength and military prowess. This narrative, intertwined with Punjabiyat (the idea of unity), Jatpana (Jatt identity), and the rural imaginary, highlights the complex interplay of cultural identity, socioeconomic status, and power dynamics in Punjab.

While Punjabiyat represents a harmonious unity, Jatpana and the rural imaginary expose the societal challenges and inequalities within Punjabi culture. Despite Punjabi music’s apparent universality in capturing Punjabiyat themes, it’s predominantly the Jatt Sikhs who claim this narrative. The power to assert their dominance over Punjabi identity stems from their socioeconomic advantage, perpetuating a distinct, casteist, and gendered Jatt identity that clashes with the egalitarian principles of Sikhism.

The globalisation of Punjabi culture and its fusion with other musical genres have ushered in a complex, multilayered identity

The globalisation of Punjabi culture and its fusion with other musical genres have ushered in a complex, multilayered identity. However, the commercialisation of Punjabi music, blending with Western influences, has inadvertently perpetuated harmful cultural values like sexism, hypermasculinity, and patriarchy. The music today has ‘the same homogenised cultural values of other popular musical forms such as hip hop’, (Varma, 2005). The homogenisation of these values, akin to popular forms like gangsta rap, restricts diverse representation and reinforces detrimental gender norms within the industry. In essence, while Punjabi music initially embodies the spirit of unity and cultural richness, its commercialisation and fusion with global influences have inadvertently perpetuated harmful societal norms, reinforcing power dynamics and limiting diverse perspectives within the representation.

Punjabi pop culture and its reinforcement of patriarchal gender roles

Punjabi music, while beloved, operates within a troubling framework that perpetuates entrenched gender roles and reinforces the systematic marginalisation of women in society. Through lenses like feminist theory, and male gaze theory, the music’s insidious impact becomes starkly evident.

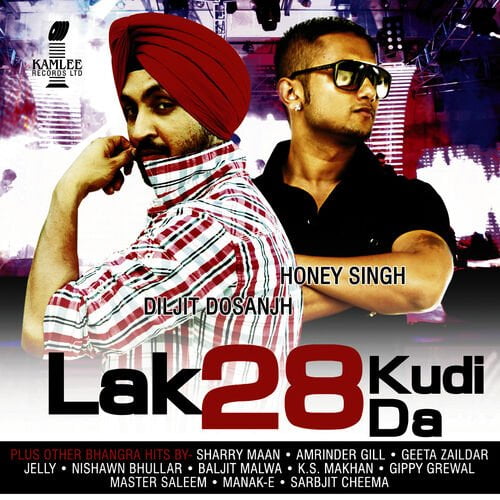

Feminist theory underscores how Punjabi pop culture solidifies traditional gender norms, often objectifying women in music videos and perpetuating unrealistic body standards. Whether, it’s Geeta Zaildar’s ‘Burraahh’, which has the lyrics ‘Ho Char Gayi Jawani Kuriye Kare Burrraahh Burrraahh Tere Lak 29 Kuriye’ (loosely translated- girl you have just attained youth, I’m excited now that your waist is also 29) or Diljit Dosanjh’s ‘Lak 28 Kudi Da’ which has the lyrics ‘Lak twenty-eight kudi da, forty-seven weight kudi da’ (loosely translated the girl’s waist is 28 and weight is 48).

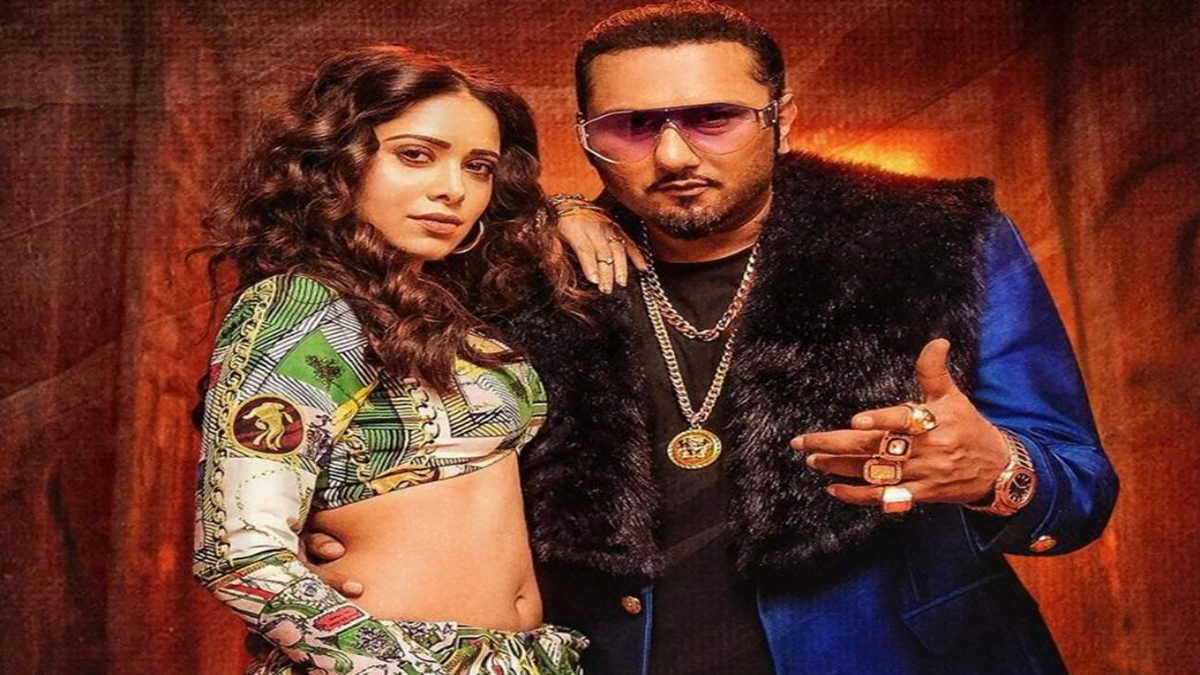

Both of these songs are just one of the million songs objectifying women and promoting idealistic body standards. Through Punjabi music, these standards are propagated to the audience, ‘The objectification of women in music videos perpetuates stereotypes, reinforces rape culture, and increases body dissatisfaction’ (Karsay et al., 2018). The normalisation of such songs has become so common that a song needs to have elements of misogyny like that in the song ‘Volume One’ by Honey Singh for women to get offended. Not only objectification, women are often portrayed in limited submissive roles, such as being the “perfect” wife or needing to be saved.

In Mankirat Aulaukh’s song ‘Kadar’, in the music video, the women can be seen performing all the duties of a perfect wife like handing the husband things even shoes and in return asking for mere respect. Then she gets pleased when her husband does the bare minimum. Overall, ‘Women are largely absent from Punjabi pop culture. When they are present they fall into a limited number of roles that have them silenced, objectified, needing to be saved or sought after as prises.’ (Bal, 2021). This limited representation reinforces heteronormativity and the male-female binary while failing to acknowledge the experiences of marginalised groups.

The Male Gaze theory reveals how Punjabi music’s visual representation further objectifies women, positioning them as mere commodities or conquests for men’s consumption.

The Male Gaze theory reveals how Punjabi music’s visual representation further objectifies women, positioning them as mere commodities or conquests for men’s consumption. From Jaz Dhami and Honey Singh’s ‘High Heels’, treating a woman like a replaceable item, to songs like ‘White Brown Black’, equating women to possessions, the music industry diminishes women’s agency, reducing them to checkboxes on a list of objects.

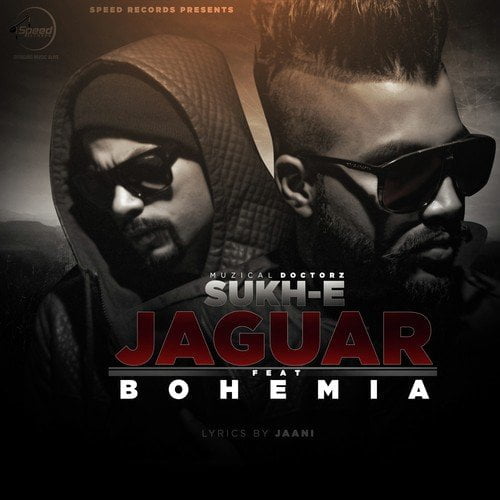

Songs like Sukh-E’s ‘Jaguar’, painting women as materialistic and demanding, or Honey Singh’s ‘Brown Rang’, objectifying and demeaning women, perpetuate harmful stereotypes, undermining the diversity of women’s experiences. The intersectional lens calls for acknowledging diverse experiences and marginalised groups excluded from mainstream representations.

Songs like Sukh-E’s ‘Suicide’, in which the man manipulates the woman and threatens her for affection, perpetuate a culture disregarding women’s consent, contributing to a hazardous societal norm.

In essence, Punjabi music, despite its popularity, operates within a framework that reinforces harmful gender stereotypes, objectification, and patriarchal values. Through various critical theories, it becomes evident how this music serves as a vehicle for maintaining power dynamics, upholding the status quo, and perpetuating the systematic subordination of women.

Construction of Punjabi Jatt masculinity

The construction of Jatt masculinity in Punjabi music and culture is rooted in the influence of the old feudal land-owning elite, despite the fact that feudalism is no longer prevalent in Punjab. Through the language of expression and aspiration, this culture portrays Jatt masculinity as dominant, symbolising pride and supremacy for Jatt men. Unravelling this hypermasculine construct requires dissecting lyrics.

Glorification of violence is another common theme portrayed in songs like ‘Chitta Kurta’by Karan Aujla, and ‘Guerrilla War’ by Amrit Mann.

Glorification of violence is another common theme portrayed in songs like ‘Chitta Kurta’ by Karan Aujla, and ‘Guerrilla War’ by Amrit Mann. These songs are some of the thousands of songs that show a hypermasculine man who asserts his dominance in society and is in constant pursuit of power. The current glorification of gun culture is not something new to the Jatt community. It stems from the fact, that historically Sikh men have always maintained a distinct identity. From fighting for their religion against the Mughals, and having revolutionary leaders like Bhagat Singh, to militancy and Operation Blue Star the Sikhs have always derived a certain amount of pride from identifying as brave and fighting for their community.

The need for protection through the years translated to the glorification of not only masculinity but guns as well. The portrayal of Jatt men as powerful and dominant is often associated with the use of weapons and guns. This image of masculinity not only reinforces gender stereotypes but also perpetuates violence and contributes to the normalisation of gun culture. Critical theory would argue that the glorification of gun culture in Punjabi music and media is not simply an innocent expression of cultural identity but a reflection of power relations in the past that have influenced the community. The overbearing identity of the Jatt community, as discussed by Gangahar and Kapil (2022), is therefore not just a matter of cultural pride but a way of asserting dominance and maintaining a particular social order.

Overall, in the following excerpt, Mooney does a wonderful job of expressing what most themes in Punjabi Pop represent:

‘[L]yrics articulate masculine and even hypermasculine values: labour, industry and self-sufficiency in agriculture; loyalty, independence and bravery in political and military endeavours; the development and expression of virility, vigour, and honour; the machismo of sharāb and glassies, and at times gangsters and guns; and an appreciation of the—objectified—beauty of Punjabi and especially Jat women.’ (Mooney, 2013, p. 295)

In conclusion, the intersections of caste and gender in Punjabi music have a deep-rooted impact on the way we perceive and understand our society. It is essential to recognise and challenge the problematic tropes and representations that perpetuate harmful ideologies. By untangling the knots of sexism and caste in Punjabi music, we can strive for a change in which ‘Lak 28’ wouldn’t be promoted and ‘Jatt da Muqabala’ won’t matter.

References

- Bal, J. (2021). Toxic Masculinity and the Construction of Punjabi Women in Music Videos. Gender Issues, 38(2), 200-209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-020-09264-1

- Gangahar, M., & Kapil, P. (2023). Negotiations within a cultural phenomenon: Sidhu Moose Wala and a changing Punjab. South Asian Popular Culture, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2023.2171312

- Hall, S. (1990). ‘Cultural identity and diaspora’. In J. Rutherford (Ed.), Identity: Community, Culture, Difference (pp. 222-237). London: Lawrence and Wishart.

- Mooney, N. (2013). ‘Dancing in Diaspora Space: Bhangra, Caste, and Gender among Jat Sikhs’. In Sikh Diaspora (pp. 279-318). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004257238_014

- Karsay, K., Knoll, J., & Matthes, J. (2018). ‘Sexualizing media use and self-objectification: A meta-analysis’. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 42(1), 9-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684317743019

- Varma, S. K. (2005). ‘Highly commended: Quantum ‘Bhangra: Bhangra’ music and identity in the south Asian diaspora’. Limina: A Journal of Historical and Cultural Studies, 11, 17-27. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.225676880315636