The Supreme Court of India has decided to replace the term “sex worker,” in its legal handbook on gender stereotypes with the term “trafficked survivor,” after a group of anti-trafficking NGOs raised concerns that the term “sex worker,” promotes gender stereotypes.

Anurag Bhaskar, deputy registrar, CRP, Supreme Court of India, informed that the CJI has accepted the change in an email to one of the NGOs requesting the change:

“Based on your suggestion, the nomenclature/word ‘sex worker,’ is being changed to the following: ‘Trafficked victim/survivor or woman engaged in commercial sexual activity or woman forced into commercial sexual exploitation,'” the email read, stating that the change will be updated soon in the handbook.

This decision comes after a group of NGOs under the banner of Anti-Human Trafficking Forum including ARZ (Anyay Rahit Zindagi) from Goa; Prayas from Mumbai; Prerana from Maharashtra; KIDS from Karnataka; Nedan from Assam, VIPLA from Maharashtra; SPID from Delhi; New Life Foundation from Manipur among others had written to the CJI, requesting to reconsider using the term “sex worker,” in the glossary of terms in the “Handbook on Combating Gender Stereotypes,” published by the Supreme court in August this year:

“Most women are forced, kidnapped, lured, and trafficked into situations of commercial sexual exploitation. By using a generic term like sex worker, one may be assuming that all women engaged in commercial sexual activity may be in this out of free and positive choice. It negates the reality that most women enter the trade through force or fraud, and many remain in it out of negative choice due to lack of better alternatives.”

Sex trafficking: a ground reality in India

Targeting mostly Adivasi women and girls, both within and across national borders, sex trafficking is truly a social malaise that India, as a country grapples with. According to India’s National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), over 6,500 human trafficking victims were identified in the country in 2022 and 60 per cent of them were women and girls. The numbers might be even higher because accurate reporting is difficult in such cases.

Most women who enter sex work in India do so, not out of free will but as victims of sex trafficking and pimping by fraudsters who lure them. The most exploited victims who fall prey to human trafficking are young girls from disadvantaged Dalit and Adivasi communities or low-income families. Sex trafficking in India, therefore, is an intersectional issue, which encompasses gender, class and caste.

Most often, young women are lured by traffickers and pimps who promise them better lives and income. In some cases, they are trafficked by men on the false pretext of love and marriage. Families, too, especially those who struggle economically, sell off their daughters to prostitution in order to live off their earnings. The Banchhada community in Madhya Pradesh are known to groom their girls to enter prostitution through generations in order for the male members of the community to live off their earnings.

The perception of women as commodities, systemic violence based on gender and generational poverty is what fuels the flesh trade in India. ARZ, one of the NGOs which requested the Supreme Court to update their handbook had stated that under the Immoral Trafficking Prevention Act (ITPA), 1956, while women have the choice to engage in commercial sexual activity, anyone who forces or lures them into this activity shall be prosecuted including those living off their earnings. Section 2 (f) of the ITPA, 1956, defines “prostitution,” as the sexual exploitation or abuse of persons for commercial purposes, and the expression “prostitute” is to be construed accordingly.

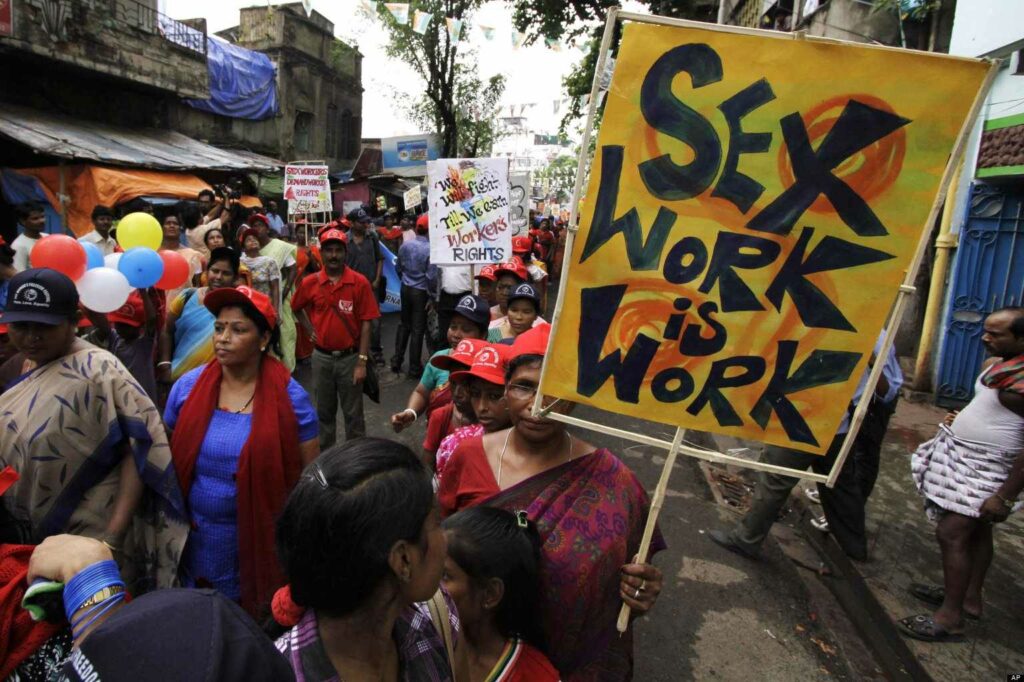

Sex work: the issue that divides feminists

The question of sex work often is an issue that bifurcates the feminist movement. Anti-prostitution feminists, often dubbed the anti-sex stream of feminists consider prostitution as well as pornography a result of the patriarchal world order which commodifies women’s bodies and turns them into sex objects for the male gaze.

Pro-prostitution feminists believe that sex work is work that is taken up by the free choice of a woman and it should be respected as such. It must be noted that even “pro-sex” feminists differentiate sex work from forced prostitution and trafficking.

In a global context, especially in the Western world, sex work can be and is a choice made out of free will, with women taking ownership of their bodies and sexuality, asserting the need to respect sexual labour as a valid form of work through sex worker activism, in nations of the Global South, including India, sex work is often not a choice but a result of trafficking or extreme poverty. Since women in sex work across the world are not a monolithic and homogenous identity, their choices or the lack thereof, lived experiences and struggles vary according to the intersectionalities in their identities.

The approach to sex work therefore should be case-sensitive, focusing more on each person rather than falling prey to the homogenising endeavour which groups sex workers all across the globe as an entity which thinks, acts and believes similarly.

Is the Supreme Court’s decision taking away agency from women?

As has been said before, the approach to sex work must vary from case to case. While it is true that most women in India are trafficked into prostitution, or make the “choice” to enter sex work due to the extreme pressure of poverty (in which case, can it be considered a “choice,” after all?), it cannot be ignored that the term “sex worker” provides respectability and agency to women in this profession. The legitimisation of their lived experiences and physical labour as “work” is at the end of the day, empowering to women, who are shamed and shunned otherwise.

It might be argued that the decision of the Supreme Court to replace the term “sex worker” with “trafficked survivor” therefore takes away the agency of these women and further perpetuates their victimisation.

It is also important to note here that sex work can also include participation in pornographic websites, some of which like OnlyFans, are popularly thought to empower women with direct income and safety online. In India, though, such websites are not an option for women.

The discourse regarding the updated legal handbook, therefore, is a testament to the precarity of the lives and livelihoods of women in sex work. It is indeed difficult to find an inclusive legal term for women that does not group all of them as either perverted “prostitutes” or forever “victims” without agency. Thus, the handbook of legal terms must be open to amendments and updates, as the discourse around sexual labour grows and evolves down the years.

About the author(s)

Ananya Ray has completed her Masters in English from Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India. A published poet, intersectional activist and academic author, she has a keen interest in gender, politics and Postcolonialism.