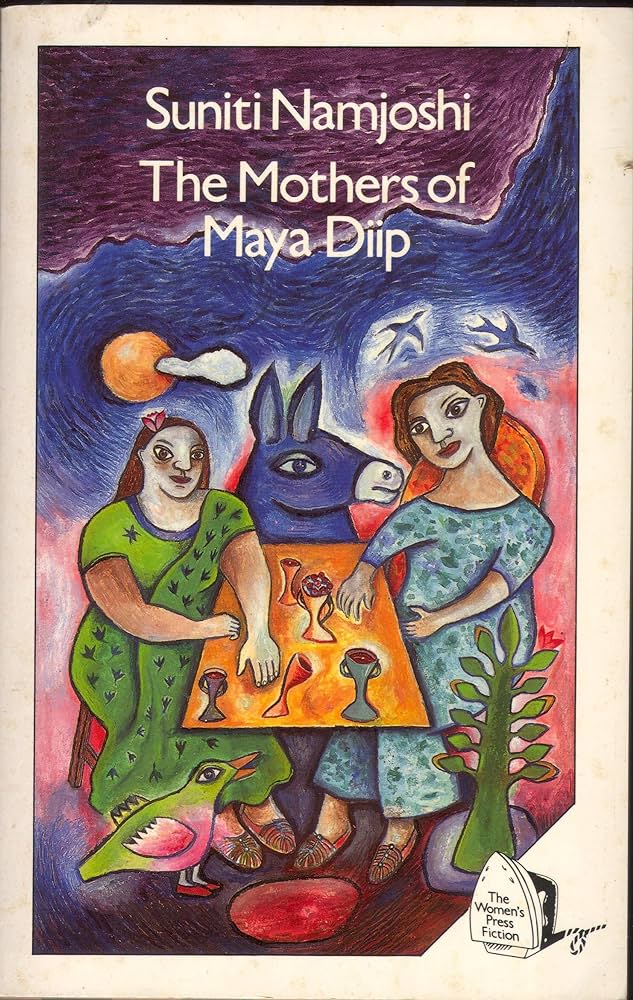

Identity is a dual sword that can both empower and weaken, for it is that entity which solidifies a human existence, but in that process also makes it rigid and inflexible, immune to the changing flow of time. Gloria Anzaldua writes, ‘Identity is not a bunch of little cubbyholes stuffed respectively with intellect, race, sex, class, vocation, gender. Identity flows between, over, aspects of a person. Identity is a river – a process.’ It introduces us to Namjoshi’s excellent articulation of identity as a constructed concept; opposed to being an essentialised entity as shown in her The Mothers of Maya Diip.

Performing gender

Whether it is Monique Wittig’s concept of ‘straight mind’ used to explain how heterosexuality is woven into our very being – speaking, feeling, thinking, processing – making it invisible in our wider culture to spot and critique or Gayle Rubin’s ‘charmed circle’ which illustrates the sex hierarchy propagated by various power relations in our society, binarising the “good/normative” from the “bad/non-normative”, gender performativity has always been under scrutiny. We see it following the focus within queer debate against an identity-based/assimilationist politics as its primary means of resistance.

Judith Butler writes how, ‘this view of performativity implies that discourse has a history that not only precedes but conditions its contemporary usages’ which is why ‘Queer’ is understood under queer theory as a ‘verb’, as something we do and not something we are (or are not). Butler explains how performativity exercises a ‘binding power’ because it ‘accumulates the force of authority through the repetition or citation of a prior, authoritative set of practices’. We are not our gender we uphold the binary oppositions in a gendered society by repeatedly doing our gender.

Adrienne Rich too questions this performativity as she critiques how, ‘for women heterosexuality may not be a ‘preference’ at all but something that has had to be imposed, managed, organised, propagandised, and maintained by force’ through a system of pleasures and privileges awarded to the ones who conform. Thus, Butler has argued that the maternal body does not precede culture: like gender itself, ‘the maternal’ is socially constructed which is why Lesbian existence, ‘comprises both the breaking of a taboo and the rejection of a compulsory way of life’.

Utopic Maya Diip: a queer heterotopia

In Suniti Namjoshi’s utopic matriarchy blooms a heterotopia when Jyanvi, the queer rebel enters, ready to destabilise the naturalised and essentialised position attributed to motherhood. She issues the question, ‘Don’t the lives and longings of women matter?’

In Maya Diip, the matriarchate society is such, where to be a woman who is a mother is the only open identity to embody, otherwise the label of being a childish woman awaits, lest you are not sent to exile for being a “heretic”.

In Maya Diip, the matriarchate society is such, where to be a woman who is a mother is the only open identity to embody, otherwise the label of being a childish woman awaits, lest you are not sent to exile for being a “heretic”. The performative aspect of womanhood is collectively decided by the Mayan society to be motherhood. Anyone falling outside of what Michel Foucault explains as ‘the multiplicity of force relations’ is not a ‘woman among women’ for the Mayans.

Like the Houyhnhnm land in Gulliver’s Travels, Maya Diip too eliminates the possibility of erotic desire and emotional intellect, where Jyanvi could not achieve the status of being a lover without first becoming a mother and where the Mayan mothers normalise the dehumanisation of ‘pretty boys’ to semen machines who are left to ‘turn to foam’.

Motherhood: truth or a discourse?

Motherhood in Maya Diip then becomes less an innate truth that needs to be uncovered and more a discourse that is produced by systems of knowledge (Foucault) and repetitive actions (Butler). With a utilitarian fervor, it is upheld by autocratic means of indoctrination where ‘not to love children, or, at least, to say that you don’t, is sacrilege’ and ‘it’s the duty of every Mayan to sacrifice herself for the welfare of the children’.

The women here unlike the people of Omelas do not even get a chance to choose and walk away because they are made to internalise the fact that ‘No Mayan would want to escape’ and eventually succumb to a destiny of willful ignorance to the execution of their autonomy or end up becoming the imprisoned child of the cellar like Jyanvi.

Demythifying the essentialisation of motherhood

Namjoshi by presenting a society that is the binary opposite of patriarchy, ‘subverts both the male-centered humanism of the West and the androcentric hegemonic erotic ethos of India’ writes Harveen S. Mann. Her utopic land of essentialised motherhood is made with the sole purpose to critique its subject, leading her readers to problematise the “natural” association of motherhood with female bodies.

Chodorow has explained how women come to mother as a feature of their social settings rather than it being a result of ‘biology and instinct’. Both Judith Lorber and Anne Fausto-Sterling have thus argued, ‘that bodies are not naturally male and female; that not only gender, but also sex, is a social construction’.

Parenting instead of mothering/fathering

Shelley Park argues that ‘adoptive mothers ‘queer’ the maternal body by de-linking motherhood from the body’s reproductive capacities’. Perhaps we should question, why is mothering associated with ‘femaleness’ and can fathers be ‘mothers’ as well? They certainly can in Namjoshi’s fabulist creation as we meet the men of Ashagad who embrace their mothering responsibilities sincerely.

LGBTQIA relationships offer us a window to look past our binary worldview of mothers and fathers and try to understand ‘parents’ whose role in the life of their child is not limited by their sex, gender or sexuality.

We are also reminded of the drag mothers in Paris is Burning, where motherhood is queered and taken beyond its normative gendered restrictions. LGBTQIA relationships offer us a window to look past our binary worldview of mothers and fathers and try to understand ‘parents’ whose role in the life of their child is not limited by their sex, gender or sexuality.

Popular representation

In the 2019 film Portrait of a Lady on Fire by Céline Sciamma we meet Marianne and Héloïse, two women trying to make sense of their identities and desires beyond their prescribed sexualities and patriarchal subscriptions. They are on fire, burning, and they burn through each other. The 2016 film The Handmaiden by Park Chan-Wook also brings to screen a lesbian relationship between Sook Hee and Lady Hideko, who thrive because they have each other despite the endless obstacles and sick perversions of the omnipresent men.

In the 2015 film Carol directed by Todd Haynes, we can see the pathologisation and criminalisation of motherhood for Carol because of her lesbian identity where she’s at the risk of losing her only child’s custody she cherishes dearly as opposed to the figure of her “husband” who wanted to keep Carol chained to him by using the child as a collateral. In the 2016 film Moonlight directed by Barry Jenkins we meet Chiron, a black child who isn’t performing the way society wants him to perform which is why he is isolated, targeted and violated. He too has a mother, a woman who comes from the heteronormative structure, who is losing herself in drugs and eventually leads to Chiron’s self-destruction as a result of communal violence enacted on his psyche.

Such representations push us to critically engage and answer Lorber’s question where she asks, ‘when we label all parenting done by men ‘fathering’ and all that done by women ‘mothering’, are we helping to naturalise notions of sexed bodies, rather than seeing them as socially constructed?’

Break the binary, move towards intersectionality

Namjoshi’s vision exposes the socially constructed nature of binary oppositions where the, ‘lesbian utopia is nothing but maya, an amusing illusion, a consolatory dream’ writes Srijita Saha. Namjoshi may be suggesting that unless we as a society realise the necessity of autonomy over one’s own body for each individual, every system we become a part of – a homogenous queer nation or a hetero-patriarchal nation – we will remain equally oppressed, trading one tyrannical master for another.

Works Cited

- Namjoshi, Suniti. The Mothers of Maya Diip. Women’s Press (UK), 1989.

- Anzaldua, Gloria. The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader. Duke UP, 2009.

- Barker, Meg-John. Queer: A Graphic History. Icon Books, 2016.

- Butler, Judith. “Critically Queer.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, Nov. 1993, pp. 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-1-1-17.

- “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence on JSTOR.” www.jstor.org. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3173834.

- Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality. 1978.

- “Suniti Namjoshi: Diasporic, Lesbian Feminism and the Textual Politics of Transnationality on JSTOR.” www.jstor.org. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1315429.

- Averett, Kate Henley. “Queer Parents, Gendered Embodiment and the De-essentialisation of Motherhood.” Feminist Theory, vol. 22, no. 2, Feb. 2021, pp. 284–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700121989226.

- Saha, Srijita. “A Quasi-Queeristan: An Analysis of Suniti Namjoshi’s The Mothers of Maya Diip as a Lesbian Heterotopia.” Interlocular Journal, Vol-1, Issue-1, pp. 58-69.

About the author(s)

Priya Jain has a Bachelors in English Honours from Delhi University. As a writer and poet she wants to strike a balance between cynicism and hope, she wants her work to have a purpose that resonates with people. She is an avid reader of literature written by women and queer writers that challenges gender norms and transgresses societal constructs. Her research interests are intersectional feminism, female rage and queerness