Cities across world have witnessed massive marches in solidarity with the Palestinian people in Gaza as the brutal Israeli invasion and bombing of the strip continues. As they called for an immediate ceasefire, these protestors flooded the streets with artistic symbols portraying the cruelties of the occupation in creative ways such as large keys, images of watermelons, or even actual fruits. Each of these symbols possess a distinctive meaning with a history in the Palestinian resistance movement.

As they called for an immediate ceasefire, these protestors flooded the streets with artistic symbols portraying the cruelties of the occupation in creative ways such as large keys, images of watermelons, or even actual fruits.

Various art forms have been integral to Palestinians’ struggle for freedom, justice and statehood. Artistic activism has helped provide a platform through which this long-waged battle for human rights could raise awareness in a larger global order shaped significantly by geopolitics and economic interests. Late Palestinian-American academic Edward Said through his work vividly brought the hardship into light the tried to evade the orientalist trap. Symbols of Palestinian identity have been successful in bringing the struggle into the spotlight amid a long history of oppression.

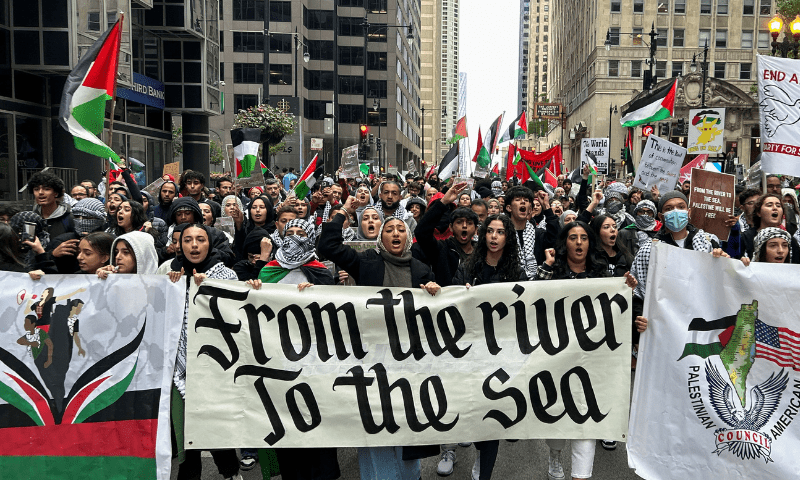

One core slogan from the movement is ‘From the River to the Sea, Palestine will be free’. This slogan is currently a topic of fierce debate regarding whether or not it is antisemitic and what it actually means. Maha Nassar, Associate Professor at the University of Arizona and a scholar of Palestinian history, dissects the narratives around this old phrase which is taking a new shape in current political discourse. While many pro-Israel groups claim the phrase is antisemitic, for most of its users it has nothing to with antisemitism. Rather, it is, as put by the US Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib, ‘an aspirational call for freedom, human rights and peaceful coexistence.’ Tlaib, the only Palestinian- American in Congress, was recently censured by her colleagues in the House of Representatives for using the phrase.

As advocates for Palestinian self-determination hear it, the phrase is a call for the return of refugees and an eventual recognition of their homeland. It is important to note that the phrase does not advocate expulsion of Israeli Jewish population but rather serves as a remembrance of a dark past and bloody expulsion that still haunts most Palestinians. For many Palestinian activists, the phrase calls for a peaceful coexistence where Arab populations in the region will have the dignity, freedom of movement, and equal rights that Israeli Jews currently possess.

The slogan is a reminder of a lost land, an aspiration to live in a peaceful world and the dream for the homeland they call Palestine. Labelling the slogan as antisemitic is a stark irony that denies agency to its proponents and represents another chapter in a long history of silencing Palestinian voices.

From Handala to the keffiyeh, a number of artistic symbols seek an end to Israeli colonial occupation in Palestinian territories. Initially circulated as to bypass the Israeli censure, over time they have created their own life and hence inspired new forms of Palestinian resistance. These imaginative art forms also distinguish between different ways of supporting the Palestinian cause. Such symbols have been equated with, and often used in support of, defiance in public and virtual spaces. However, the systemic repression of Palestinian existence tends to result in a lack of recognition that these symbols are valid expressions of resistance to colonial subjugation.

From watermelons to olive trees: symbols of the Palestinian struggle

A striking and unique symbol of resistance, the watermelon is a fascinating way to describe a long history of subjugation. It has been featured in formal art, in graffiti, on protestors’ banners, and via emojis on social media. Grown across Gaza, the fruit shares the colours of the Palestinian flag: red, green, white, and black.

Meanwhile, wearing the black-and-white keffiyeh has gained an association with demanding justice and freedom. A keffiyeh is a square-shaped cotton headdress with a distinctive chequered pattern which is unique to Arab culture. A sign of peace since ancient times, and featuring the olive tree which also has a deep connection with Palestine’s history and culture, the keffiyeh has fuelled resilience against Israeli occupation and promoted Palestinians’ connection to the land. In 1974, Yasser Arafat, then-president of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), proclaimed in his famous ‘Gun and Olive Branch’ address to the UN General Assembly: ‘Today I come bearing an olive branch in one hand and the freedom fighter’s gun in the other. Do not let the olive branch fall from my hand. I repeat, do not let the olive branch fall from my hand.’

A cartoon character known as Handala created by Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali sheds light on the harsh experiences of childhood in occupied territories. Palestinians who had to flee their homes during the bloody Nakba (“catastrophe”) of 1948 kept their keys; many of them see themselves and their descendants personified in Handala, a child refugee. The key has taken a symbolic form of Palestinians’ right to return to their original homes, which also references a principle of international law that recognises the universal right to voluntarily re-enter one’s country of origin. For displaced Palestinians, the Nakba is not an event long buried in the past; it is a recurring trauma that never stopped.

For example, the olive tree and other symbols can often be found in the paintings of artist Sliman Mansour.

These symbols recur across many art forms and represent the fight against a historical and continuing injustice. Many artists often use these symbols in their paintings, sketches and sculptures. For example, the olive tree and other symbols can often be found in the paintings of artist Sliman Mansour.

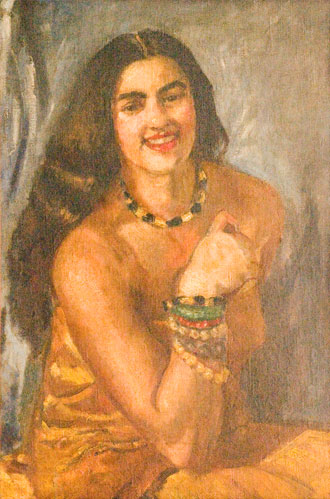

Spotlight on contemporary Palestinian artist Malak Mattar

At age thirteen, a girl in Gaza sought refuge in paints and canvas amid intense Israeli bombings. Trying to escape the ever-present paranoia of death, she found a box of watercolours that for her became a hidden route to an imaginary society filled not with missiles but with kids playing out in open.

Within the despair, trauma and suffering endured during her childhood, this imaginary world of paintings became a permanent refuge for now 24-year-old Palestinian artist Malak Mattar. Her paintings are a medium to reflect her fears and to escape the daily tragedy of looming death. Art turned out to be a therapeutic way to deal with PTSD and atrocities she had to bear in her surroundings in Gaza.

Mattar’s art predominantly depicts Palestinian women. Drawing attention to dark on-the-ground realities, Mattar claims that the women in her paintings are freer than her own reality; while she lived in Gaza, Mattar’s travel and freedom was harshly limited due to the occupation.

Mattar observed the borders of Palestine shrinking over her school years. She has survived many bombings and wars—including a deadly blast in the 2014 Gaza War that almost killed her, while her neighbours died before her eyes. Her art is an effort to remember these dear ones and their disappearing homeland. It is an act of visibilising a deprivation that has been ongoing for decades and systematically kept out of the world’s attention. Highlighting the difficulty of Palestinian artists to be able to travel as far as their artworks, she says with disillusionment, ‘Sometimes I would think the world itself is the prison, not Gaza.’

Mattar’s paintings are an attempt for Palestinian women to express their agency in a historically deprived setup. These paintings reveal the ugly nature of the occupation regime. The trauma of war is something the Palestinian woman carries within her, even while living abroad. ‘It’s not something that can be let go of, shaken off; it seeps into you and becomes a part of you. How can you process something that has not ended?’

Mattar’s paintings are an attempt for Palestinian women to express their agency in a historically deprived setup. These paintings reveal the ugly nature of the occupation regime

This insight touches directly to the hearts of Palestinians who feel a deep connection to their land. They have continued their remembrance of a homeland that is increasingly being taken away through their memories, culture and food.

These lands, from Safed close to the Jordan River in the east, to Jaffa and Haifa on the Mediterranean beaches in the west stretch from the river to the sea. In the collective Palestinian imagination—as vividly portrayed through art and symbolism—all people in the region will once again be able to walk unimpeded and in safety across that terrain.