Published in September last year, Rheea Mukherjee’s second book The Girl Who Kept Falling In Love explores the realities of falling in love in post-modern India. The narrative focuses on the protagonist Kaya, a forty-ish self-proclaimed ‘girl,’ who grew up in the USA, but has been living in India for eighteen years.

Kaya has a penchant for falling in love. From falling for Yonas, an American man of Eritrean descent in her early twenties, to being with A, a liberal Muslim man in India, Kaya’s life is depicted through the series of lovers she has had.

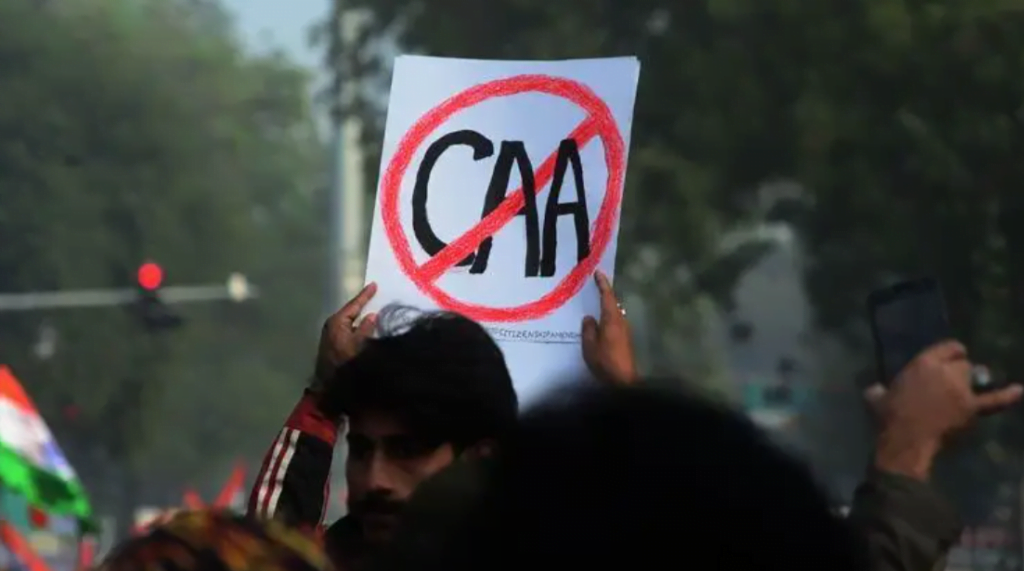

Set against the backdrop of the Anti-NRC-CAA protests that shook the nation in 2019 till the pandemic hit in 2020, the novel deals with the concepts of caste-class-gender privilege with striking self-awareness. Kaya is a Hindu Brahmin woman, hailing from a family settled in America. Through her characterisation, readers are acutely made aware of the privilege she possesses in a nation teetering at the edge of fascism. In India, Kaya immerses herself in activism, where she befriends Millie, a radical activist, and falls in love with A, a Muslim doctor.

Navigating romantic relationships in a fast-changing world

Despite ‘dating‘ many people, Kaya’s accounts focus on the Big Three of her love life: Yonas, Anna and A.

At twenty-three, Kaya falls in love with Yonas, an Eritrean-American man. It is the cross-cultural romance that she adamantly hoped would last, but like most big first loves, it does not. Kaya’s next big love is Anna, a blue-haired free spirit who harboured within herself a great sadness. Anna leaves Kaya for a professor in Amsterdam, whose child she bears and is eventually, as she predicted, ‘crushed,’ by her life. Anna dies by suicide and haunts Kaya forever in life and in love.

Kaya’s romantic tales in a world defined by difference, hate and fascism are a statement and a testament to every person’s ultimate goal- to love and to be loved.

A is a charming ‘liberal,’ Muslim man, Kaya meets at an Anti-CAA protest. A wields an infectious charm, with his irreverent humour and his ability to see right through the ‘woke,’ protest aestheticism masquerading as ‘revolutionary,’ around them. However, in a moment of insecurity, Kaya makes a mistake, which she atones for with heartbreak after A leaves her on the revelation of her secret crime.

Through all the loves Kaya has ever loved, she rediscovers herself in bits and pieces, as an empath, as a saviour and as a ‘selfish,’ woman who let a moment’s mistake redefine her entire life.

Kaya’s romantic tales in a world defined by difference, hate and fascism are a statement and a testament to every person’s ultimate goal- to love and to be loved. Whether it be cultural differences, depression or the omnipresent threat of fascism, Kaya’s attempts to triumph love over all, reiterate the utmost importance and necessity of love in a late capitalist, post-modern world.

Millie, Kaya and the starry-eyed idealism of liberal millennial India

At the anti-CAA/NRC protests, Kaya meets Millie, a radical activist with lofty ideals of social justice and progressive change. Millie is your typical protest enthusiast, who rallies against the systems of patriarchy, caste and communalism, replete with a fiery zeal and ‘woke,’ lingo that Kaya is often annoyed by.

In university spaces and left-liberal circles, the aestheticisation of protest is embodied in the way activists dress, in the books they read and in the spaces they hang around in.

Mukherjee’s novel does a stellar job of laying bare some of the hypocrisies in these cultures of protests while letting readers know the utmost necessity of such protests in a nation like ours. Kaya’s journey of learning and unlearning is facilitated not only through the love relationships she is a part of but also through such protest cultures.

When Millie is jailed for carrying a ‘Free Kashmir,’ placard at a protest, she becomes a veritable sensation, on social media, news sites and liberal circles. She gets a soft martyrdom as she had always hoped she would, according to Kaya.

Kaya’s position as an upper-caste, upper-class Brahmin woman is one that demands social, economic and cultural privilege. Kaya is self-aware, yet even as she unlearns her internalised biases, sometimes her privilege speaks through. Kaya seems to have an overwhelming need to save the ones she loves. It might be her way of expressing love, but it is reflective of her subconscious saviour complex.

The novel is an examination of the human quest for love as it grapples with activism, protest cultures and privilege in a nation marked by political turmoil.

Dystopian Hindutva in The Girl Who Kept Falling In Love

The Girl Who Kept Falling In Love moves through an all-too-familiar timeliness until it swerves into a dystopia that has the potential to become all too real. After the anti-CAA/NRC protests are squashed in the wake of COVID-19, the text takes a dystopian turn as in the final few chapters of Mukherjee’s book, India becomes a Hindu nation as all other communal identities are subsumed under one saffron Hindutva ideology.

On his marriage to Kaya, A chooses to partake in a ‘Shadification,’ which grants him the safety of a ‘Hindu Is India,’ card, thereby converting him to Hinduism. A, now Akash, becomes a shell of his past self, as Kaya and he travels in a city marked by saffron flags, enforcing a Hindu-only mandate. As Kaya says, capitalism feeds Hindutva, constructing a futuristic imagination of global Hindu power in the place of what used to be known as India, a land which prided itself on its ‘unity in diversity,’ a concept that is now long dead and buried under forgotten history.

This dystopian turn in the text reiterates the dangers the nation is in, as it dances on the edge of all-consuming fascism. In the India we see in the final pages of the book, protest is almost blasphemous. It is a nation that conflates India’s rich and diverse past with a phagocytic Hindu history that adamantly stomps its foot and claims ‘it has always been there.’

Ultimately, Mukherjee’s text is a caveat. It is a text that puts things violently into perspective, chronicling the recent past and the ebb and flow of popular dissent and mass activism. But The Girl Who Kept Falling In Love is also hopeful, as amidst all upheavals it reasserts our faith in the power of love, which, as clichéd as it may sound, has the potential to overcome the love of power, wrap itself around human existence and survive, as it always has done.

About the author(s)

Ananya Ray has completed her Masters in English from Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India. A published poet, intersectional activist and academic author, she has a keen interest in gender, politics and Postcolonialism.