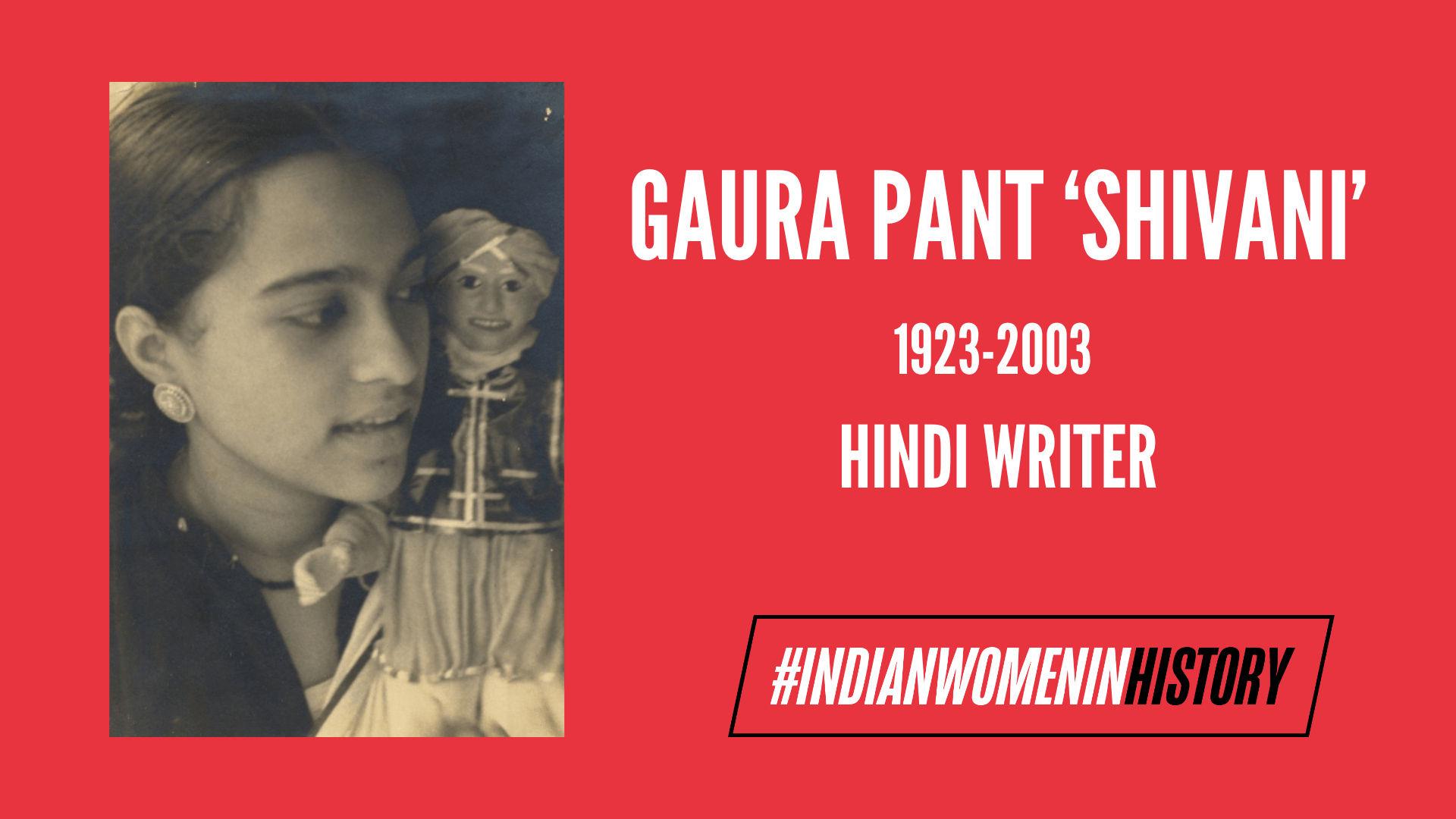

Born in 1923 in Rajkot, Gaura Pant lived to see not only the independence of the country from colonial rule but also its arrival into a new century. Throughout her life, she had to contend with various conflicting engagements, her role as a mother and a wife versus her occupation as a significant novelist and short-story writer not being the least of them. It is perhaps fitting then that she chose the pseudonym “Shivani,” for herself, which is another name for Durga – the Hindu Goddess associated with feminine strength and power, while also being the rather domestic and dutiful consort of Shiva.

Across her vast bibliography, Shivani has lent her voice to mostly female protagonists navigating life under oppressive patriarchal structures. Her motive seems to be to faithfully represent these women, and also additionally to give them the sort of agency that, in actuality, they would seldom have. This agency comes to them in the form of a fierce, indomitable spirit, the likes of which, outside Shivani’s narratives, would be crushed and forced into submission. Her depictions, therefore, are both representative of reality and aspirational in their matter.

Indeed, her daughter Ira Pande, remembers her getting letters from her readers, offering her the stories of their lives to be woven into stories of poetic justice. Shivani, if sufficiently intrigued, would oblige.

Shivani, accidental feminist?

It would seem slightly disconcerting, given the nature of her narratives, that some accounts of her push for an image of her that is thoroughly depoliticised, and for a feminist understanding that was instinctive rather than self-conscious. Mita Kapur, in conversation with Ira Pande, writes in an article in The Hindu:

“She didn’t have a political agenda, protest rallies were not her game though a lot of writers of her age had gravitated towards politics and had she walked that road, she would have made a phenomenal leader.”

A life in the public sphere, one could argue, inevitably entails politics. It is true that Shivani’s politics cannot be truly described using the rhetoric of “agenda,” and that they were anything but overt or conscious, but her belief systems informed her work as they do nearly everything else. She grew up in an age that was politically rife with debates.

Shivani effectively walked the thin line between non-conformity and controversy, and that most definitely takes a certain amount of political consciousness.

India was figuring out what it wanted to be as a nation. Women and other marginalised groups were confronted with their continued subordination despite the toppling of the oppressive crown up high. To represent select communities, therefore, in any chosen medium, was inherently political. Shivani effectively walked the thin line between non-conformity and controversy, and that most definitely takes a certain amount of political consciousness.

A large portion of her bibliography has been described definitionally as “women-centric,” and accounts are quick to dismiss the political connotations of that tag while also simultaneously using it to conceal and draw attention away from her craft.

This also meant that she was forced to contend with the supposed dichotomy of her identity, being both, a person in the public sphere, and a married woman with children. Almost all accounts of her life hinge upon this apparent contradiction which is not the case with someone like Harivanshrai Bachchan, her contemporary, and also an individual who had children. The duality did not exist here because there were no supposedly contradictory roles to deal with. Her identity as a female member of a strictly conservative household before and after marriage predisposed Shivani to a lot of conjecture and questioning. She might not then, have chosen the political route, but it chose her.

The rival claims of art and life

It is understandable, and also to be expected that Shivani would have been a product of her times. Her work often betrays sensibilities that the modern feminist reader might take an issue with like a certain disdain for denim-donning, cigarette-smoking, supposedly anglicised daughters-in-law juxtaposed with the traditional heroine the reader is meant to sympathise with. Her daughter’s memoir of her life is thus aptly named “A Conservative Rebel,” for although she grew up in a traditional Hindu family and was later married into another, her characters often undertook rebellions against conventions that she felt trapped in.

Shivani’s mother, a Sanskrit scholar who believed in abiding by domestic conventions, and her father, a Kumaoni Brahmin, a teacher, and a Diwan, instilled in her values that she later carried into adulthood. When she was eight, she was sent to Shantiniketan, West Bengal, where she stayed for around a decade. In addition to her prolific writing career, she briefly pursued singing for the radio, a career that she had to quit after marriage because her in-laws did not approve of it.

Shivani is known to write about protagonists mostly at the intersections of class and gender. Her heroines are middle-class women and it is their domestic lives which is used as fodder for the plot. Her characters rage and storm against established patriarchal norms and aim to venture beyond their lot. Her heroines often leave abusive marriages that stifle them, in an age when that would have been considered a thoughtless provocation of conservative sentiments.

Despite her focus on narratives featuring women, she was read by people, extensively and widely. She was proficient in English, Hindi, Gujarati, and Bengali, and after she wrote her first short story in Bengali, she was advised by Rabindranath Tagore to write in the tongue that she was most comfortable in.

Shivani took his advice but did not limit herself to writing strictly in Hindi. Her works are influenced by her multilingual upbringing. Subsequently, her decision to embrace Hindi as her primary medium contributed significantly to the establishment of a substantial post-independence corpus of work in Hindi literature. Amidst the lingering colonial influence in India, she managed to distinguish herself as one of the few authors who catered to the masses, with magazines fervently competing for the privilege of featuring her coveted works.

It is important to note that Shivani came from a family of means. She was born in an upper-caste family and her profoundly scholarly upbringing, coupled with her association with some of the greatest minds of the age, paved the way for her to become the most widely read Hindi novelist in the country. She was not however blind to the workings of caste and it featured in some of her best-known works, and she was critical of it when she addressed it in works like Bhairavi, wherein she talked about the Aghoris as a response to the protagonist’s traditional caste-ridden life.

Despite the themes that she dealt with, Shivani’s works were marked by a keen aesthetic sensibility. Unlike her contemporary, Ismat Chughtai, who swore by the idea that literature must hold up a mirror to society and draw attention to its vulgarity and flaws, Shivani’s prose took place amidst the most serene spots of Kumaon, featured the most conventionally beautiful women, and had extremely powerful imagery. She is said to have claimed that she could not “bear to write of ugliness in locale or character.”

Ira Pande, in her memoir, states that even in life, Shivani would attempt to run away from problems that made her miserable or uncomfortable. “In her own life, as in her writing,” writes Ira Pande, “(she) was the quintessential escapist.”

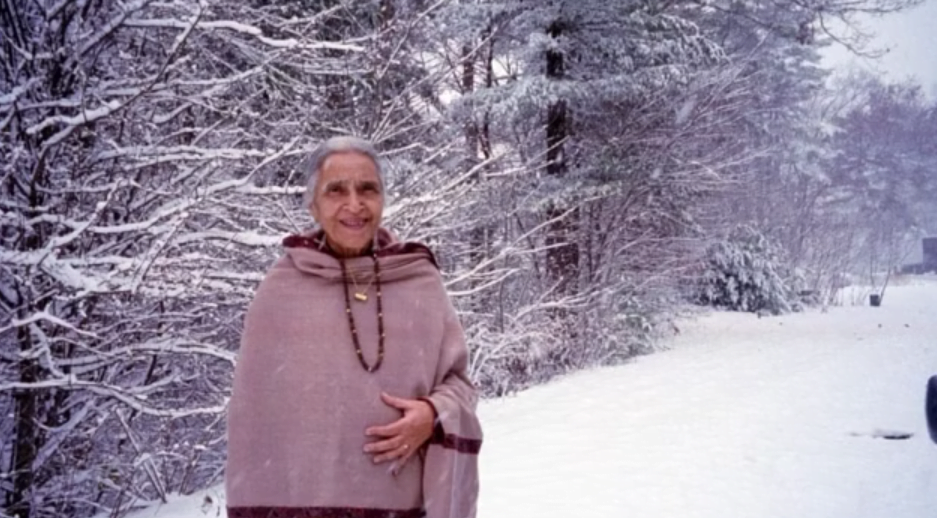

That is not to say that she cloistered herself from the world. Indeed her companions towards the end of her life were those on the margins of society and those that offered her blue-collar services.

“She donated all the award money she received to charitable organisations or used it to educate the vast retinue of helpers (she used to call it the staff of the Rashtrapati Bhavan) or marry them off. Among her friends were the local hijra, Mohabbat, the milkman, Suleiman, the vegetable vendor, the postman, and Qaif Ali, her faithful rikshawallah,” Pande writes.

The denouement

Shivani did not limit herself to any of the categories that society would have liked to put her into. She was neither confined to high-society interactions nor did she claim to be intrigued by the trappings of an ordinary, humble life. She was neither compliant nor mutinous. Like most of the women of her time, she had to find a compromise that would allow her to live her life on her terms while still adhering to the norms of society. Like most of the women of her times and beyond, she had to bargain and count her successes and ensure that her ambitions were in line with what society expected of her.

At the fag end of her life, listing out all the ways her life had been worth it to the doctor, she not only talked about her four children, eight grandchildren, and great-grandchild but also about how she would be paying for her funeral – a humble and rather understated way of referring to her career as the most sought-after Hindi writer of her age.

In the end, she resolved the conflicts of her life in her work. She navigated the dualities thrust upon her in ways so enigmatic that they enshrined her in the history of Hindi literature forever, and in doing so, she also immortalized the life and longings of the middle-class Indian woman, previously absent in the narratives preceding her.

References:

About the author(s)

Adrita Bhattacharya is a Computer Science graduate from Vellore Institute of Technology and is currently pursuing a degree in English and Cultural Studies at Christ University. She has a keen interest in Linguistics, Gender Studies, and Digital Humanities.