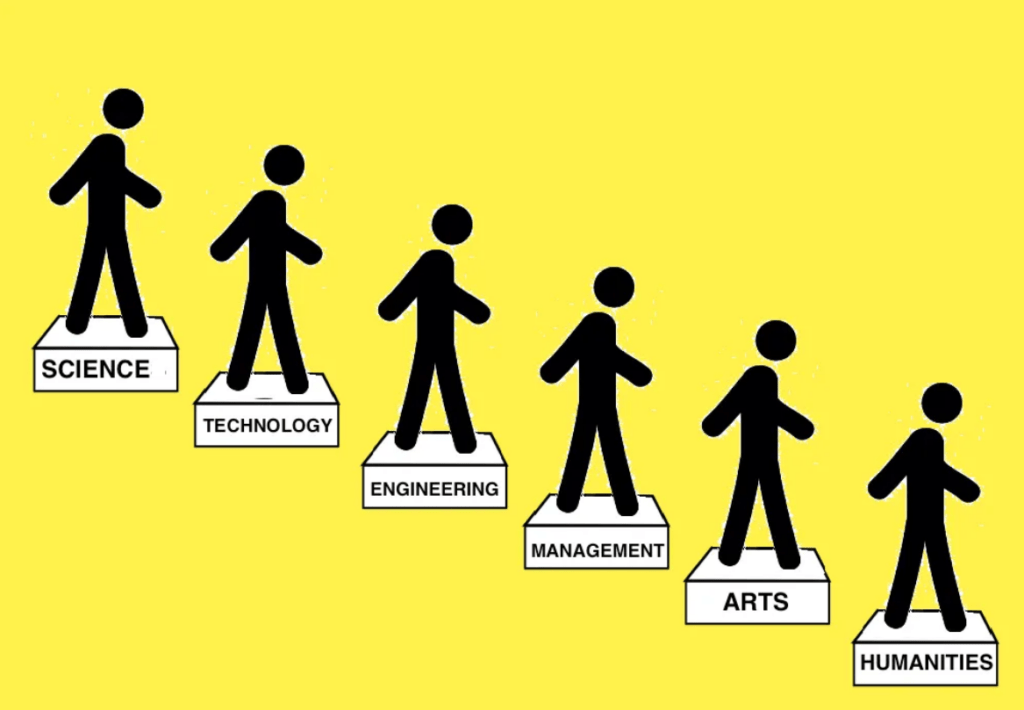

When I was in ninth grade, I was told by a boy I liked that I was “too smart to take up Arts,” when I expressed my desire to do so. In my naivete and my eagerness for validation, I took it as a compliment, but it was far from one. It was not his fault. He had, like me, grown up in an environment that convinced him that there was something significantly more valuable about the Sciences than the Humanities. However, he had found it easier to subscribe to the notion than I had because he did not incline to the Arts.

That was not, unfortunately, the last time I heard that idea asserted as fact. After tenth grade, someone told me that taking up the Humanities would leave me “no other choice but to be a school teacher in the future,” as if there was something inherently shameful about that occupation as if that is not one of the most difficult, and important occupations that exist.

In twelfth grade, a teacher, in an attempt to “inspire,” me and make me realise my “true potential,” told me that she would slap me if I ever suggested that I was meant to pursue the Humanities because I was “intelligent,” and only “unintelligent,” people pick anything other than STEM (Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics).

In my first year of Engineering, my feelings about what I wanted to do had still not changed, and someone else told me that it was my “responsibility,” to keep at it for all the women in STEM who would come after me. If someone as “smart,” as I am quits STEM, it will only reinforce the notion that women, no matter how intelligent or capable, are simply not meant for the Sciences, and will fail in life.

Now, there are worse things that people are subjected to as a result of the deeply pervasive patriarchal structures in India than being told that they are “intelligent,” over and over again. Still, these instances are evidence of a larger systemic issue. It is hard to say why people in India (and outside it) value STEM over the Humanities. If interrogated, a typical person would claim it is because STEM pays more. Why, then, does STEM pay more than the Humanities?

Is it because STEM disciplines are supposedly more “rational,” and more “empirical?” Who decides that they are hence better and worthier than the more “emotional,” and more “intuitive,” disciplines? And does it, or does it not have something to do with how skewed the gender ratios in both these disciplines are?

Some of those people did manage to convince me that I ought to stay in STEM if I am to prove my worth, and as an extension of it, that of all of womankind. Then I fell from the pedestal and stopped taking myself so seriously. Their contentions with my natural inclinations had seemed feminist, but in their heart, they demanded conformity to the same notions that anti-feminist rhetoric upholds. That anything that is associated with conventional masculinity is more estimable. That conventional masculinity is the normatively true requisite for any value. That not aspiring to succeed in STEM, is submitting to failure.

In any case, allowing an immensely sexist idea to dictate what one does with one’s life, even if it is to thwart the power of said idea is deferring to it. It is the sort of thing that gave rise to the contemporary critique of the “Pick Me Girl,” – a woman so anxious to please her patriarchal overlords and avoid judgment and derision at all cost that she tries to remove herself from any association with the conventionally feminine.

What the critics of the “Pick Me Girl,” forget is that at the end of the day, she is trying to do her best to survive and earn respect in a world that values masculine approval more. It is easier to ridicule the Pick Me Girl than even acknowledge the figurative gun held to her head.

Therefore, I do not seek to claim that any woman who takes up traditionally “masculine,” jobs hates femininity, nor that any woman who takes up traditionally masculine jobs for no other reason than because it would afford her more security – financial or social – has betrayed the core tenets of Feminism in any way.

What I do seek to do is draw attention to why, even if she feels a proclivity towards it, she cannot choose traditionally “feminine,” roles and be equally respected for her choices. What I do seek to do is problematise the hand holding the gun.

“A woman who loves other women, sexually and/or nonsexually appreciates and prefers women’s culture, women’s emotional flexibility (values tears as natural counterbalance of laughter), and women’s strength.“

– Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens

When individual women transcend the boundaries established by patriarchal structures to find a place for themselves in male-dominated arenas, the structures seldom change. It means that these women as individuals won the game, but the game is still designed, refereed by, and played according to systems of patriarchy.

In our preoccupation with the confinement of women to certain personal or occupational roles, we often do not pay attention to why it is that these confined spaces are also trivialised. Traditionally feminine occupations have historically offered valuable services, and yet, one fails to recognise their contributions as vital. Most of the labour undertaken by women has been underpaid, or not paid at all.

Women’s labour as homemakers is not compensated nearly enough for how taxing it is and it is only outside the general workforce because it is predominantly performed by women, and hence devalued to the extent that it is invisiblised. Indeed, many claim that the reason there is a substantial wage gap between men and women is that women deliberately opt for lower-paying jobs. Is that true or do the jobs women opt for end up getting paid less?

To see an instance of how women’s work is undervalued, one need only consider occupations like nursing. Traditionally a female-dominated occupation, nursing is paid much less than most other healthcare professions. It is a high-skill job that demands expertise and exertion and is still not valued as much as it should be given its necessity. A Wire article draws attention to how nursing in India is not only gendered but also caste-based. Quoting Panchali Ray, a professor at Krea University, Andhra Pradesh, it states:

“…the root of this problem was the “societal contempt for corporeal and affective labour” that is performed by women and of members of the so-called ‘lower caste’ groups, while the scientific and technical jobs assigned to men are glorified.“

Another example of how women’s labour is understated and undervalued is, of course, the profession of teaching. Primary school teachers in India, predominantly women, are overworked and underpaid. Primary school teaching, however, is an occupation that the country cannot do without.

A research article on Occupational Feminisation describes the phenomenon of devaluation – the reduction of wages in a sector as women gradually enter it. There is ample evidence therefore that no industry can be judged as inherently more or less valuable because a lot of the claims of “value,” are based on extremely sexist ideologies parading as common-sensical knowledge.

A year ago, I chose to switch career streams and take up Humanities despite all the declarations that I had often nodded along to, about how something I was naturally inclined towards was less valuable, simply because people like me were inclined towards it. In hindsight, all claims of its inherent inferiority seem to me to be influenced by a flawed perception of what must be cherished and idolised. The hand holding the gun to my head is still there, for it must stay, and I may be wrong, but I swear I see it shuddering, if not a lot then certainly a little, if not with fear then certainly with confusion.

About the author(s)

Adrita Bhattacharya is a Computer Science graduate from Vellore Institute of Technology and is currently pursuing a degree in English and Cultural Studies at Christ University. She has a keen interest in Linguistics, Gender Studies, and Digital Humanities.