Set in the 1800s in Victorian England, RF Kuang’s Babel is a treatise on the dilemma of the colonised, who has to contend with the British empire’s complacency and claims of benevolence on the one hand and the abject horrors it has inflicted on the other.

Against this backdrop, Kuang introduces a genius, if slightly convoluted, element of what she calls “silver working.” The idea is that the loss of meaning incurred by translating a word from one language into another can be stored in bars of silver which can then be put to various applications. The British Empire, having discovered this property of silver, exploits the languages of the Orient to meet its ends. Besides the existence of silverworking, Kuang remains faithful to history.

Some criticisms of Kuang’s setting and theme claim that they do not coalesce to form a whole that makes sense, given that an England with literal magic at its disposal does not significantly differ from its historical version. Like all magical realism historical fiction, Babel is not concerned with writing an alternate history with silver working at its centre. Silver working is not the point of the book, it merely aids it. It is a concentration of all how the Empire borrowed from the same cultures that it considered beneath it to pave its path to greatness.

Kuang chooses to focus on language as the central reflective point of all the Empire’s crimes, and therefore, her universe employs translation magic.

Kuang writes in Babel: “English did not just borrow words from other languages; it was stuffed to the brim with foreign influences, a Frankenstein vernacular. And Robin found it incredible, how this country, whose citizens prided themselves so much on being better than the rest of the world, could not make it through an afternoon tea without borrowed goods.”

Kuang’s premise is demanding. The encyclopedic knowledge of around ten to twelve languages that she might have needed to acquire to write this book, not only the etymological origins of words in all those languages but also their semantic nuances, is worth a degree in Sociolinguistics. And yet, Kuang is not a linguist. She specialises in East Asian Languages and Literatures. The research that has gone into the creation of this narrative is impeccable and beyond reproach.

As a native speaker of one of the languages that she explores in the books, albeit to a lesser degree than the other languages, I could not have arrived at the social, pejorative sense of the phrase “Gora Sahib” (Fair-skinned Sir/Master) is used in. The quantity and quality of her research truly reflect her academic inclinations.

Kuang’s ideological vessels

Babel is about the individual in systems of oppression, about how they rise, and how they fail to. The entire narrative, a bildungsroman of sorts, centres on Robin Swift, who was rescued by the mysterious Professor Lovell from a cholera-struck Canton where his mother had just died, asked to shed his name, forced to “rise above” the supposed failings of his race, and trained to be able to one day employ translation magic to aid the Imperial project. He is so grateful for the life that has been afforded to him, after the threat of destitution and squalor, by the same systems of oppression that had condemned him to destitution and squalor in the first place, that it takes him the better part of the book to realise the despotic mechanisms of the Empire.

The rest of his cohort at Oxford, where he goes to study translation and silver-working, are similar individuals who have nothing to gain and everything to lose by raging against the Empire. Ramy, Ramiz Rafi Mirza from Kolkata, is glib, audacious, and a lot more exposed as a supposed outsider in Oxford than Robin is.

Victoire Desgraves, a Haitian student with instincts of self-preservation that enable her to want to survive in the face of hopelessness when most narratives would not have allowed her that, rises as a subversion of the roles characters of her race ordinarily fulfil in narratives that concern them.

And Letitia “Letty” Price, the daughter of a British army general, who is at Oxford against the wishes of everyone in her family is a stand-in for the white suffragette, whose understanding of justice is exclusionary when it comes to race. They are a cohort of, as Kuang puts it, people who could kill each other but also die for one another.

And then of course, there is Professor Lovell, whose cruelty and villainy seem caricaturish and over-the-top to the white reader. His hatred for the non-European races and his mistreatment of Robin seem contrived only to those who are not familiar with Churchill’s “dog-in-the-manger” analogy, or the horror stories of Jallianwala Bagh, among several other instances of deeply absurd colonial contempt. To those who are familiar with these, Professor Lovell seems to be an accurate representation of the Empire’s attitude towards its colonised nations.

Kuang’s narrative is more ideological than it is character-driven. Her characters, each, are representative of a general political thought process, and hence allegations that claim that her characters lack depth do not adequately consider these characters’ purpose. They are devices for the construction of an argument. She admits in an interview that she started by outlining the arguments that she would like to present and that those arguments “were the heart of the story” way before Robin was even conceived of.

Babel and its themes

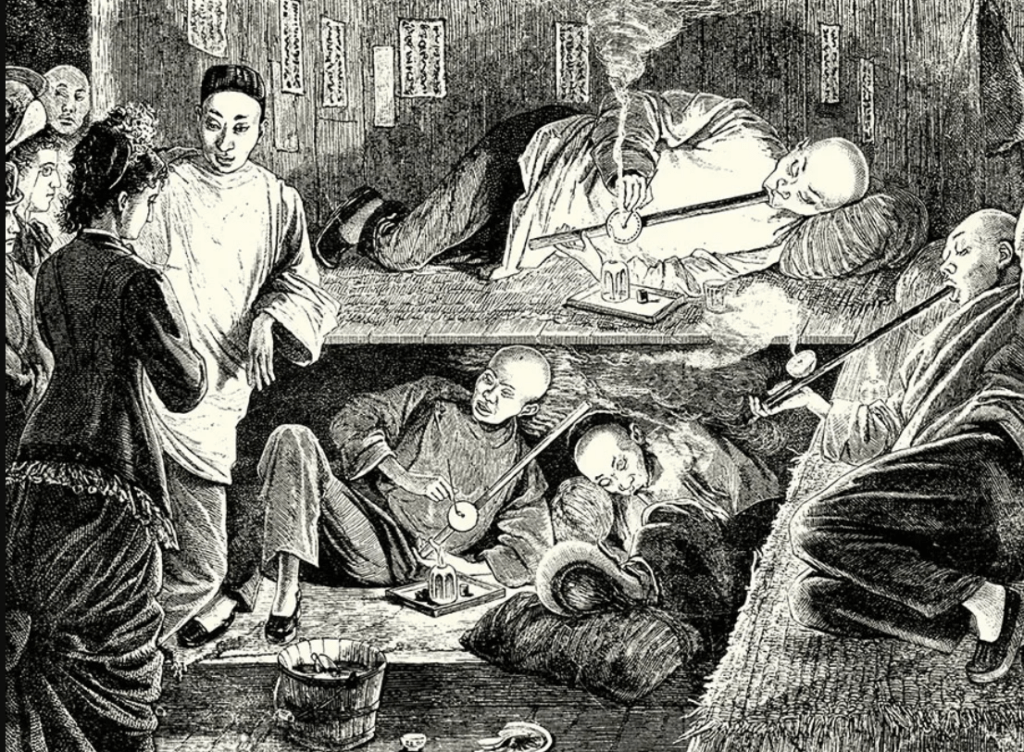

Another theme that Kuang touches upon is the opium crisis in China that the British wanted to exploit and then refashion it, as their commitment to free trade. Robin, in a moment in which the Empire’s atrocities truly dawn upon him after a visit to his country of origin, listens as Ramy points out that the British were forcing Ramy’s countrymen to grow opium so that they could sell it for profit in Robin’s country, that the benefits of the free trade that the Empire championed so aggressively can only be reaped by the monopoliser, the coloniser.

The White Man’s Burden, then, was necessarily a capitalistic project undertaken for exploitation.

Kuang’s motive behind writing this narrative was to present a defence of “violence” or what has generally been deemed “violence” in resistance of any sort. It interrogates the principled aversion that some have to movements that inconvenience structures of power, claiming that it is unnecessarily aggressive and even criminal to protest, a discourse that is especially rampant in India currently, after the fallout from the anti-CAA movements and the Farmers’ protests.

Kuang wants to direct the reader’s attention to the question of who the aggressor is. The people who withdraw their services when the empire wrongs them? Or the empire that would rather let harm befall its civilians than bend a knee?

Indeed, her metaphor of silver-working and linguistic exploitation is a more effective allegory than it appears at first glance since the Empire did exploit the assets of the colonies to the extent that it claimed that the colonies could not completely appreciate their epistemological products.

Indian classical literature, like Kalidas’s Abhignam Shakuntalam, for example, was considered too morally ambiguous to be fit for consumption by the “barbaric” Indian natives, while the “civilised” European mind would be able to appreciate it for its pastoral imagery and be unaffected by its depravity. This epistemic thievery, one could claim, is what Kuang’s fictitious Institute of Translation at Oxford represents, and is guilty of.

A balance of style and substance

Babel reads like a thesis through which Kuang is presenting her scholarly findings and ideas. The work is rife with footnotes – etymological analyses in some cases and cheeky asides in others – and it is both, a critique and a representative text of the dark academia genre. Its conflict in terms of form resonates with Robin’s dilemma, who, despite having been confronted by the dark side of Oxford, found solace for the first time in his life in its grim hallways.

Robin is not the reader’s proxy. The narrator, via a postcolonial ideological framework, is talking to the reader about Robin’s journey in an attempt to prove something, in an attempt to explain why people revolt, and why they must do that.

Kuang mentions in Babel: “History isn’t a premade tapestry that we’ve got to suffer, a closed world with no exit. We can form it. Make it. We just have to choose to make it.”

Kuang is not overly optimistic about the fruits of rebellion. She does not claim that it always, or ever, begets success. Her resolution is grim, and some would claim anti-climactic. There is no reason however to reduce revolutionary movements to their end result.

The Chittagong Uprising, for example, did not have a favourable result but it had value as a movement and deserves to be in history books, and for the same reason, Robin’s story needs to be told. His recovery from how he, for the entirety of his life, had been coerced into compliance with the empire was the end result. His, and the reader’s, ideological awakening was the end result that Kuang was aiming to achieve, and through her meticulous inquiry and craft, managed to, and in the process created something that is fit to be considered a modern classic.

Kuang’s irreverence to the sentiments of her white readers, and her disinterest in whether or not her narrative alienates them can be read as a dismissal of the oppressor’s humanity, but this critique forgets that colonisation was in no way, shape, or form, humane. In her polemical attack on the history of imperialism, she also does not fail to address the fact that institutions, academia in particular, still uphold their colonial legacies and do not adequately attempt to redress them.

To sum up, Babel’s methods are vigorous, but the ends more than justify the means. It exposes the materiality of the imperial project, the performativity of the coloniser’s mission, and the brutality of even the banalest of the colonial atrocities.

About the author(s)

Adrita Bhattacharya is a Computer Science graduate from Vellore Institute of Technology and is currently pursuing a degree in English and Cultural Studies at Christ University. She has a keen interest in Linguistics, Gender Studies, and Digital Humanities.