Caste in India is inescapable, much like the air we breathe – omnipresent, yet often unnoticed until it reveals its polluted or scarce form. Just like air, caste system is an integral yet often invisible component of our social fabric. For those who benefit from its hierarchical structures, caste may remain a subtle backdrop, but for those marginalised by it, its oppressive presence is acutely felt.

For those who benefit from its hierarchical structures, caste may remain a subtle backdrop, but for those marginalised by it, its oppressive presence is acutely felt.

This dichotomy became clear to me during a conversation with a friend about authorship on caste discrimination. I had opined that ‘anyone with a sense of justice and empathy for the marginalised should write about caste.’ My friend countered, suggesting that while it’s important to discuss caste, such narratives should be grounded in personal encounters and experiences, not appropriated from others. This exchange was a profound moment for me, leading to an epiphany: I must write from my own interactions with the caste system, detailing my firsthand observations and reflections.

Childhood encounters

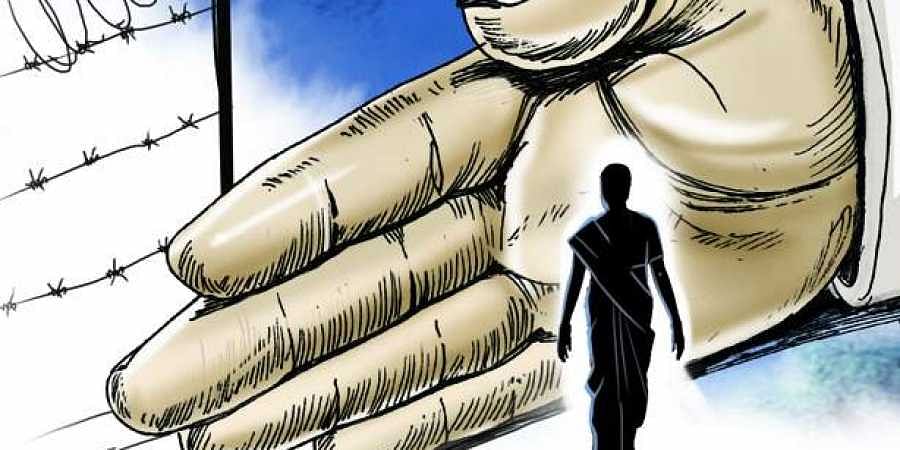

I vividly recall the first incident, though its true significance eluded me at the time. It occurred around 2007 or 2008, I was around twelve or thirteen years old. It was very hot outside and on top it the summer was marked by electricity and water shortages. Our village had a public handpump (Nalka) situated right in front of our home, a vital water source for the community. On this particular day, I went to fetch water in a Matka (a traditional pot). I would regularly see a lady in our street, a familiar figure from the village, who worked as a sweeper. Each day, she performed her duties diligently, a quiet constant in our daily lives.

Needing assistance, I asked her to help lift the filled Matka onto my head. Surprisingly, she declined, gently but firmly stating that my mother might not approve of her touching our Matka. This refusal left me perplexed and, admittedly, a little frustrated. I couldn’t understand her reluctance. Upon my insistence, she offered to keep watch over my Matka while I fetched someone from home to help. This brief interaction, seemingly mundane at the time, would later resonate deeply with me. It wasn’t until much later in life that I understood the gravity of that moment.

The lady, a Dalit, was painfully aware of the potential repercussions of touching an upper caste’s water pot. In the traditional caste hierarchy, the touch of a Dalit was often misconceived as “polluting”, particularly when it came to something as essential and communal as water. A simple, helpful gesture could have been construed as polluting. This incident, insignificant as it seemed then, unveiled the insidious nature of caste – invisible yet deeply embedded in our everyday lives. At the time, I was completely unaware of her caste or the rigid societal stratification that governed our seemingly simple exchange. The caste system, with its unspoken yet stringent rules, controlled our actions, influencing even those subjugated by its hierarchy.

The caste system, with its unspoken yet stringent rules, controlled our actions, influencing even those subjugated by its hierarchy.

As I reflect, I recognise how I was cocooned in my own caste bubble. Growing up a Jat (dominant caste in Punjab, Haryana and Western Uttar Pradesh), I had unconsciously been comfortable in my caste identity, flaunting it in my daily interactions as though it were a personal triumph rather than a mere accident of birth. I was oblivious to the experiences of those who could not openly express their caste identity without fear of discrimination. My friends, predominantly from my own caste, shared similar cultural and dietary habits, further insulating me in a homogenous environment.

Academic journey and caste blindness

As a girl, I was additionally sheltered by societal norms that subtly indoctrinated ideas about “good” and “bad” girls, setting invisible yet powerful boundaries around me. As a child, the complex layers of social stratification were beyond my comprehension. Yet, this interaction was my unwitting initiation into the nuanced power play of caste, an integral part of the social fabric that quietly orchestrates our lives. Unintentionally, I had been an active participant in perpetuating caste distinctions, normalising the practice of “othering” those outside my social circle. This “othering” shaped my social interactions and reinforced the dominant caste ideologies and biases that were ingrained in me.

One incident in particular continues to resonate with me, not as a source of pride, but as a stark reminder of the privileges I unknowingly enjoyed in a caste-driven society. This privilege was the luxury of ignorance. This incident occurred during my academic journey, serving as a profound turning point in my understanding of caste. This realisation didn’t dawn upon me in the rural landscapes of Haryana, but within the intellectual halls of Delhi University where I was pursuing my Master’s degree in Political Science. Despite my educational background, I continued to exist under the veil of caste blindness, a privilege afforded by the people of dominant-caste status. It was a phase marked by a lack of genuine interest in critically examining and understanding the deep-rooted complexities of the caste system.

I vividly remember during my masters one of our teacher introduced a new course titled ‘Dalit Bahujan Thought’. My initial reaction to just the title was dismissive: ‘Here we go again, another discourse on caste and the Varna system.’ I erroneously believed I already understood enough about the caste system, viewing it as a relic of the past. This attitude reflected my privileged position, which allowed me to remain detached from the realities of caste and its pervasive influence, as well as its ongoing political significance in contemporary society.

The real shift in my perception began during my PhD coursework when I stumbled upon Gulamgiri by Jyotiba Phule and The Annihilation of Caste by Dr B.R. Ambedkar.

The real shift in my perception began during my PhD coursework when I stumbled upon Gulamgiri by Jyotiba Phule and The Annihilation of Caste by Dr B.R. Ambedkar. Engaging with Mahatma Phule and Dr Ambedkar’s critical examination of the caste system shattered the comfortable bubble of ignorance I had been living in, bringing me face to face with the harsh realities of caste dynamics. It prompted me to delve deeper into the subject, exploring the intricate connections between caste, power, and politics.

My journey towards a more nuanced understanding of caste dynamics was significantly enriched by engaging dialogues with my Dalit and Bahujan peers. Hearing about their lived experiences, characterised by narratives of systemic injustice and the persistent stigma and shame associated with their caste identities from an early age– was both heart-wrenching and eye-opening. It was a stark contrast to my own upbringing, where caste was a badge of honour rather than a mark of oppression. It made me realise the extent to which I had been a part of, and complicit in, a system that perpetuated such deep-seated discrimination. Their narratives of endurance and resilience against the backdrop of societal prejudices provided me with a much-needed perspective, fundamentally altering my understanding and approach to caste.

The complexity of caste and gender

The most recent incident I recall occurred during my fieldwork in Haryana last year. I was conducting a group interview with about eight or nine women in a village. After completing my questions, they kindly invited me to join them for tea, offering an opportunity to observe their conversation further. These women, all belonging to Haryana’s dominant caste, shared their experiences of participating in the year-long farmers’ protest. They spoke of feeling a sense of liberation for the first time in their lives, an empowerment born from their active role in the protests. As daughters and wives of farmers, they discussed the challenges of sustaining their families on dwindling farming incomes.

But it was their personal stories of enduring domestic violence that struck me the most. Enduring violence often becomes a twisted norm for women, where the body is a ledger of unspoken suffering – each mark a testament to feeling less human, each moment a battle between weakness and the will to survive. This profound reality, revealed in their tales, highlighted the distressing normalisation of such violence in their lives, underscoring the resilience required to navigate a world where their pain is often unseen and their struggles unvoiced.

Here were women, who had stood at the forefront of a movement for rights and justice, now effortlessly perpetuating harmful stereotypes against Dalit women.

However, the tone of the conversation took a sharp turn when they began discussing the difficulties one woman was facing in finding a suitable bride for her son, highlighting the persistently low sex ratio in Haryana. Some women light-heartedly suggested looking for a bride from a Dalit family. The group’s laughter took a disturbing turn when one woman remarked that Dalit women were undesirable due to their alleged ‘bad smell‘. This casual, derogatory comment was not just a display of caste prejudice; it reinforced the deeply entrenched binary of purity and pollution associated with caste.

This moment was a jarring contradiction to the themes of liberation and unity they had previously discussed. Here were women, who had stood at the forefront of a movement for rights and justice, now effortlessly perpetuating harmful stereotypes against Dalit women. Their laughter and dismissive comments were a stark reminder of how caste prejudices can overshadow shared experiences of gender discrimination and marginalisation. It highlighted the complex intersectionality of caste and gender issues, revealing how deep-rooted biases can remain entrenched, even in those who themselves have been subjugated within a patriarchal society.

I learned a vital lesson from my experiences: understanding and challenging deep biases is key to changing society. From personal realisations to broader social issues, I understood how much work we still have to do in fighting caste and gender discrimination. It’s a reminder for all of us to recognise our roles in these systems and to work together for a fairer and more just world.