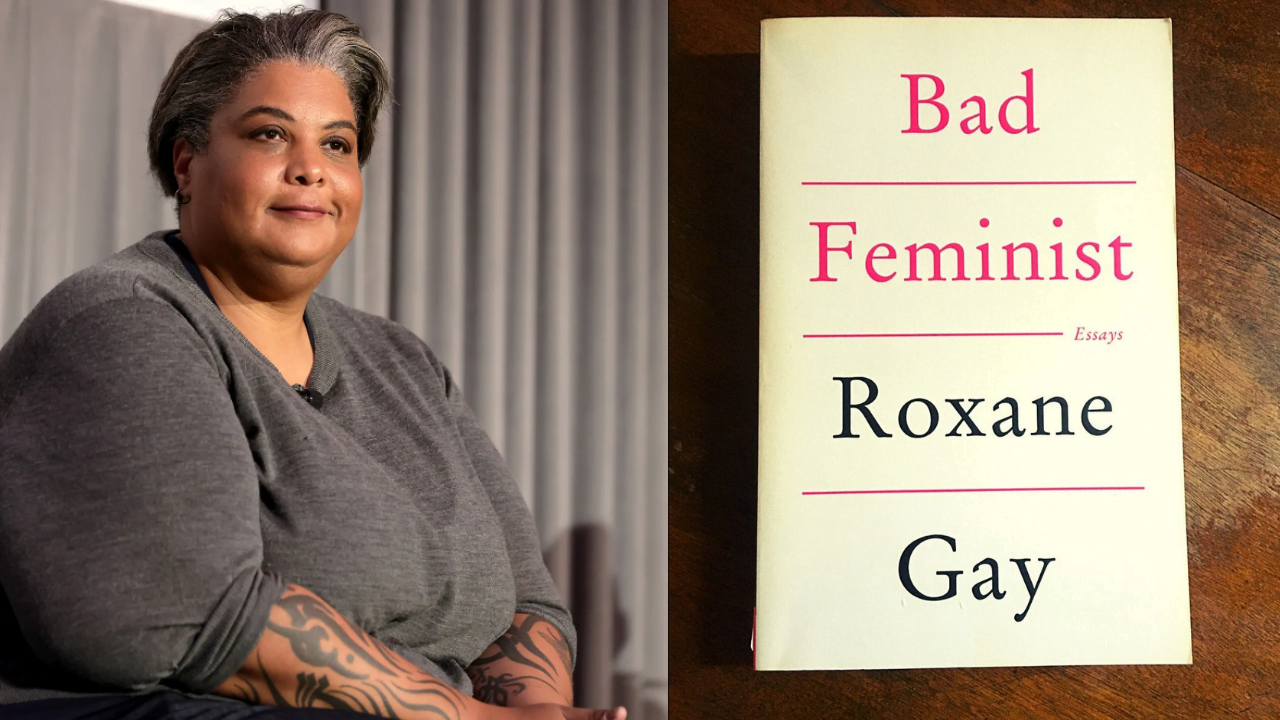

Through a series of multi-faceted essays ranging from themes of violence, desire, and activism, to critical analyses of films, television series, and romance novels – American author Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist (2014) posits how it is better to be a flawed feminist than not being one.

She writes with a certain vulnerability, interspersing her observations and critique of popular culture with personal anecdotes and reflections. Her writing exemplifies how being vulnerable does not always have to equate to being powerless. With her striking wit and inspiring courage, she empowers the reader by permitting them to exist with their imperfect feminisms as long as their heart remains in the right place.

In her own words, she is “raising her voice to show all the ways we have room to want more, to do better.”

Holding space for contradictions within feminism

Gay’s book generates more questions than answers, the chapters are rarely conclusive. Instead, it examines the topic at hand from varied feminist perspectives, depicting how feminism itself is complex and ever-evolving. She makes space for nuance within discussions.

For example, in her essay The Illusion of Safety/The Safety of Illusion, she opines that trigger warnings are ineffective because writers cannot possibly anticipate and protect their readers from all possible triggers, and neither should they be expected to. “There is nothing words on the screen can do that has not already been done,” she writes.

In her essay The Illusion of Safety/The Safety of Illusion, she opines that trigger warnings are ineffective because writers cannot possibly anticipate and protect their readers from all possible triggers, and neither should they be expected to.

But towards the end of the chapter, she also holds space for those who need and believe in the safety of trigger warnings, “I do recognise that in some spaces, we have to err on the side of safety or the illusion thereof… We can neither presume nor judge what others might feel the need to be protected from.”

A similar dichotomy appears in the essay The Trouble with Prince Charming. Referring to the Fifty Shades trilogy, Gay writes about the dangers of conflating obsessive and controlling tendencies in a partner with desirability and passion. She also laments the lack of ethical BDSM representation in the plot, leading the readers to make wildly inaccurate assumptions and generalisations about the lifestyle. The done-to-death trope of the virginal good girl saving the troubled bad boy from his past and changing him for the better is cringeworthy at best and severely damaging for young women at worst.

Still, it was an “uncomfortable realisation” for her that she could find gratification in something that was so terribly written. She acknowledges that the trilogy does privilege female sexual pleasure to a great extent, which has contributed to its popularity. “Chances are you will be turned on by something in these books… In nearly all the sex scenes, Christian is meticulous about pleasuring Ana. He lavishes her body with all manner of sexual attention.”

The dialect of feminine vulnerability

Roxane Gay not only conveys her vulnerabilities and insecurities as a feminist but also as a woman. She is mortified by public speaking even though she works as a professor. She is desperate to win at Scrabble. She agonises over the thought of dying alone, unmarried and childless. She fakes her orgasms on some occasions because they are time-consuming. Her captivating authenticity makes it easier for the reader to relate to her.

In the essay Not Here to Make Friends, she explores the notion of likability and why it matters so much to us. Likability has various components – moral approval, affection, and the need to belong. In this age of social media, the topic is especially relevant when the online economy largely depends on users liking or approving another user’s posts and life updates. It is a culture that hinges on “relentless affirmation.”

She also explores how in popular culture, unlikeable male characters are labelled as the antihero – dark, troubled, and yet compelling; whereas female characters are standoffish and unpleasant.

This debate around likability also spurs conversation around who is likeable. How likeable are fat people in our collective consciousness? There is a personal account of Gay living life as a fat person in the essay Reaching for Catharsis, where she was sent to a fat camp as a teenager. She writes about the obsession we have with our bodies as a culture, “Our bodies move us through our lives… I think about my body all the time – how it looks, how it feels, how I can make it smaller, what I should put into it, what I am putting into it, what has been done to it, what I do to it, what I let others do to it. This bodily preoccupation is exhausting.”

It would be a disservice to talk about feminism and not talk about intersectionality. The author addresses the question of privilege and oppression in her essay Peculiar Benefits. She is a woman of colour and comes from an immigrant family, but she acknowledges that she has class privilege.

Drawing on her perspective, she reminds us that the “spectre of privilege” constantly seems to haunt the online discourse, and advocates for navigating the discussions around privilege through observation rather than accusation.

Women’s bodies are not your playground

Bad Feminist, apart from being a self-exploration of how the author practises her feminism, is also a rigorous critique of how the patriarchal society has failed its women. She advocates for reframing the conversation around sexual violence by focusing on the ‘rapist culture,’ instead of the oft-employed term ‘rape culture,’ thereby placing the onus on the perpetrator and not the victim.

Gay advocates for reframing the conversation around sexual violence by focusing on the ‘rapist culture,’ instead of the oft-employed term ‘rape culture,’ thereby placing the onus on the perpetrator and not the victim.

She also takes issue with the appropriation of the word ‘rape,’ for any depicting any sort of violation, big or small. The chapter Some Jokes Are Funnier Than Others evaluates how commonplace it has become to use women’s traumatic experiences as fodder for comedy. “Rape humour is designed to remind women that they are still not quite equal. Just as their bodies and reproductive freedom are open to legislation and public discourse, so are their other issues,” Gay elaborates.

Even the way we report rape in the news has been irresponsible, she argues in the essay The Careless Language of Sexual Violence. Victims continue to be invisibilised, and the aftermath of a gruesome incident continues to be trivialised.

In a lot of ways, compassion still seems to lie with the perpetrators. The crime itself becomes a spectacle rather than being treated in a dignified manner. One can thus surmise that writing and language will always be a political act whether one intends for it to be or not.

The book starts and ends with the assertion of Gay’s feminist identity but also highlights her openness towards this feminism being flawed. Bad Feminist disrupts the idea of an ‘essential‘ feminist ideology.

“Feminism will better succeed with collective effort, but feminist success can also rise out of personal conduct,” is a clarion call for women to keep fighting the good fight. Above all, with this book, she ensures that women’s stories matter and are heard as they constantly try to make sense of this ever-changing world.

About the author(s)

Divyani is a media and research professional with a background in critical cultural theory. Her core interest areas are digital cultures, sexuality, and mental health. She loves annoying her cat and a good cup of coffee.