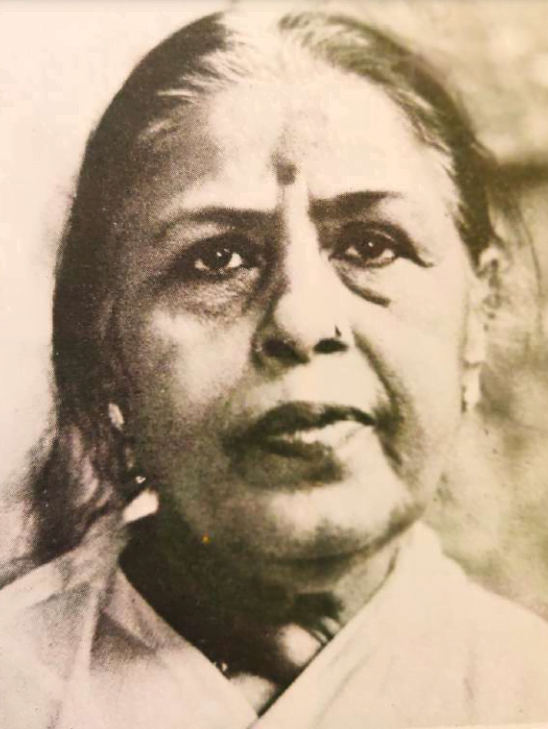

Benaras, also known as modern-day Varanasi, has a rich cultural history with various art forms such as music and dance rooted in its folk culture. Siddheshwari Devi was born in 1908 into a family with a long musical lineage. Her grandmother, Maina Devi, was an acclaimed singer who passed on the mantle to Siddheshwari’s aunt, Rajeshwari Devi. After Siddheshwari’s mother passed away while she was still an infant, she was brought up in her aunt Rajeshwari’s household.

According to multiple sources, she began her musical training under Pandit Siyaji Maharaj, a celebrated Sarangi player. He introduced her to the professional music sphere. Subsequently, she also trained under Rajab Ali Khan of Dewas and Inayat Khan of Lahore. Bade Ramdasji from Benaras was considered to be her main guru.

For the initial few years of her career, Siddheshwari’s performances took place mostly at household functions, where she was instructed to sing by her aunt – where Gandharvas performed traditionally. In a time when the norm for most ‘respectable,’ women was to get married and move to their in-law’s house, she chose to become a professional artist and move away from her aunt’s house to live independently.

There are different accounts of why she chose to move out of her aunt’s house. According to singer and writer Sheila Dhar, she left because she fell in love with a man; whereas according to writer and producer Amrit Lal Nagar, it was because she had had a falling out with a patron and thus angered her aunt. Given the matrilineal system prevalent in courtesan households, this would have been a significant change in young Siddheshwari’s life.

Thumri and its close association with tawaifs

Siddheshwari Devi was best known for the semi-classical musical form of thumri, which has existed as a liminal space belonging to women in the world of Indian classical music. It is dependent on connecting emotions of play, desire and sexuality and counts on several renderings where the same phrases and lyrics could bring up experiences ranging from betrayal to seduction, as well as pain.

Thumri hails from the Indo-Gangetic plains and emerged more clearly as a genre by the 1830s. It was majorly performed by tawaifs – highly sophisticated courtesans trained in the art of singing and dancing. Usually performed for patrons and in courts, it served as a vehicle for interpretative dance. Tawaifs had a vast repertoire beyond thumri, but thumri was the only form that was intricately linked to dance, notes researcher Lalita du Perron.

“How are feminists to understand this style, these women? Does one reject it as a male-gaze form and therefore one that is demeaning to women? Does one keep the ‘tunes,’ and rewrite the lyrics? The women – does one read them as politically powerful women…or does one ‘read,’ them as unfortunate victims of a patriarchal society, objects of elite male lust, objects of both class and gender oppression as women needing to be rescued from a demeaning life?” writes musician Vidya Rao in her piece exploring thumri as a feminine voice.

As a performer, while the tawaif was celebrated and sought after, she was also an outlaw, given her non-marital status and the stigma which was attached to women who were in the public gaze. The space occupied by the tawaif was not only marginalised but simultaneously seen as ‘obscene,’ and ‘deviant,’ in the society.

During the time that the courtesans occupied central space in Banaras, they owned extensive property with rich furnishing and elegant furniture, their patronage came from the ruling elite in Banaras. On several occasions, they were invited for performances in the court, in temples and in the homes of princes, they were even called to perform in religious ceremonies. They sang songs of anger, rejection, separation, sexual longing and ecstatic passion that contained within them, the poetry of thumri.

Siddheshwari’s early career and singing style

The Indian musical scene in the 1920s and 30s was dominated by the princely states. The rajas and nawabs were often connoisseurs to singers. Siddheshwari Devi’s debut performance was at the Calcutta conference where she performed a wide range of khayals and thumris. After her first musical appearance at the age of 18, invitations to perform started pouring in from all over India.

Over the next few years, she earned high praise for her performances in Jaipur, Jodhpur, Bhopal, Lahore, Mysore, Kashmir and various other states which used to patronise classical music during that time. She performed in the zenana at Rampur State supported entirely by female accompanists. Thumri was Siddheshwari’s forte but she also performed renditions of other classical forms such as khayal, dadra, chaiti, and kajri.

In her early days, she is said to have been deeply impressed by the singing of female contemporaries such as Gauhar Jaan, Zohra Bai, and Malika Jaan. Talking about her style of music, Siddheshwari Devi is reported to have said, “Although my thumri is fully of the Benaras ang, I incorporate elements of the khayal into it. You may say that my thumri singing is khayal angapradhan (khayal prominent).” She added variety by bringing in elements from the tappa musical form as well.

‘Cleaning Up,’ of the Thumri

During the period between 1920 and 1960, thumri became increasingly independent from dance. In the late 19th and 20th centuries, attitudes towards dance changed, and the subsequent anti-nautch campaigns meant that professional female singers were being pushed into the margins. Saba Dewan’s documentary “The Other Song,” shows how Mahatma Gandhi refused to recognise the work of the tawaifs for the Non-Cooperation Movement until and unless they stopped their “unworthy work that made them worse than thieves.”

In the late 19th and 20th centuries, attitudes towards dance changed, and the subsequent anti-nautch campaigns meant that professional female singers were being pushed into the margins.

In modern India, a tawaif’s art was only deemed acceptable when their lifestyle and sexuality were distanced from it. Academic Jyotsna Kapur notes in her review of Dewan’s documentary that with the rise in Hindu nationalism and a desire to control spaces of excesses, the ‘moral,’ was differentiated from the ‘immoral,’ through a lens of colonial morality. As the Victorian moral code was internalised, the kotha of the tawaif became a dangerous, hazardous site that allowed illicit pleasures and thus sucked away at male vigour.

Author Prabhat Ranjan in his book Kothagoi describes how the “puritanical zeal,” of the nationalist movement and the government turned all the Bais into Devis and Begums. Female artists started being asked to produce marriage certificates to sing or record music for government institutions such as All India Radio (AIR). Therefore thumri, and by extension the women singers, had to distance themselves from dance to survive.

These were the times during which Siddheshwari Devi was navigating her career and art form. It was a relentless battle to not just be recognised for her music but also to be treated with dignity.

Later career and accomplishments

As the music scene in India kept evolving, public concerts in towns and cities started to pop up. Artists who were confined to the local level or a particular gharana started becoming more and more popular. Siddheshwari’s career reflected this change in the pattern of her musical performances and she became an eminent concert artist. She enjoyed singing through the night at the oldest annual Harballabh music festival held in Jalandhar, Punjab. She also sang at the Tansen festival in Gwalior and Swami Haridas Sangeet Sammelan in Mumbai. She was also an acclaimed studio artist at Akashvani and Doordarshan.

In 1965, Siddheshwari Devi shifted from Benaras to the Indian capital city Delhi, reflecting her growth into an artist known and celebrated pan-India. She was invited to teach at reputed institutes such as the Bharatiya Kala Kendra as well as the Kathak Kendra. She became “an institution by herself in view of her enormous repertory and heritage of a rich musical tradition.”

She received various awards and accolades for her contribution to the sphere of Indian classical music, including the Padma Shri by the Government of India in 1966. In the same year, she received the Sangeet Natak Academy Award for Hindustani Classical Music, the highest Indian recognition given every year to a performing artist.

Amongst other recognitions, she received an honorary D.Litt from the Rabindra Bharati University in Calcutta and the prestigious ‘Desikottama,’ from the Vishwa Bharati University in Shantiniketan, West Bengal. She passed away in March 1977.

References:

- Siddheshwari Devi – Queen of Thumri by Aditi Desai

- About Siddeshwari Devi by Susheela Misra

- Thumri, Ghazal and Modernity in Hindustani Music Culture by Peter Manuel

- Fact, Fable and the Unknowability of the ‘real’ Siddheshwari Devi by Shreya Ila Anasuya

- Thumri as Feminine Voice by Vidya Rao

- Film Review: The Other Song by Jyotsna Kapur

- The Other Song (Documentary) by Saba Dewan

About the author(s)

Divyani is a media and research professional with a background in critical cultural theory. Her core interest areas are digital cultures, sexuality, and mental health. She loves annoying her cat and a good cup of coffee.

Thank you for the careful scripting to avoid the male shadows and discriminatory societal practices.