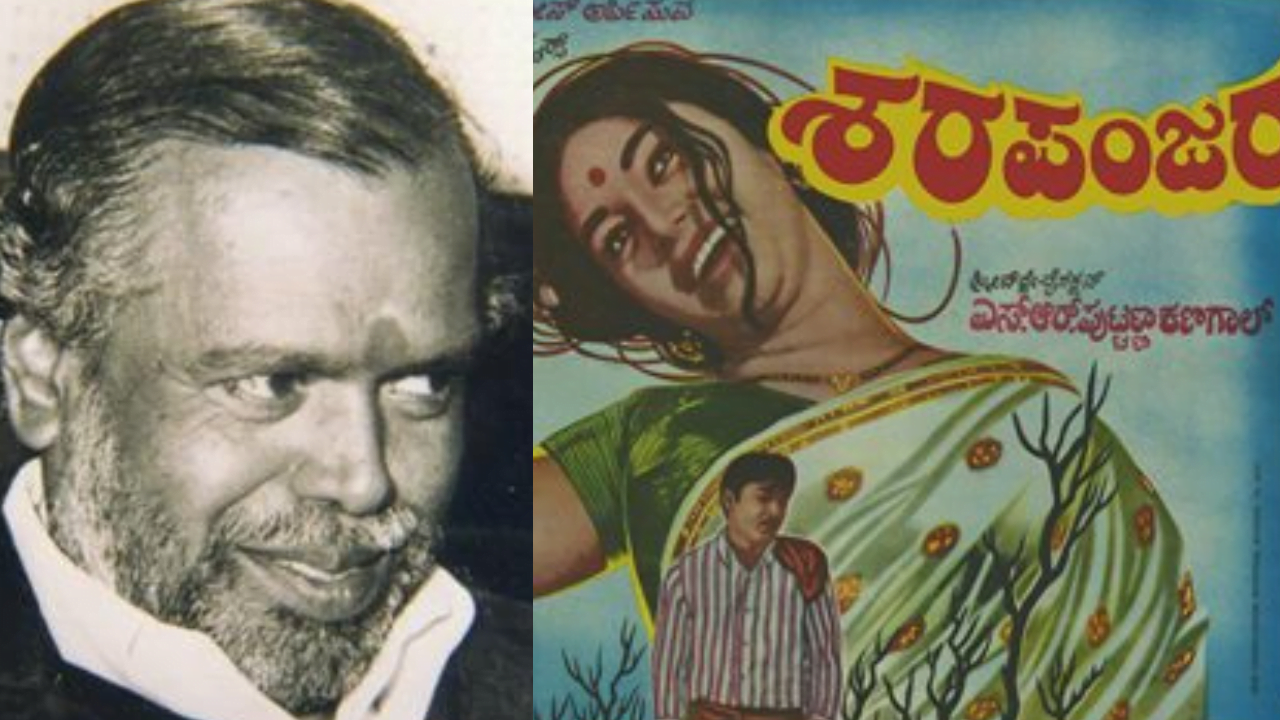

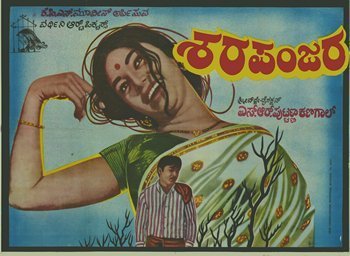

Amid the parallel cinema movement in India, when Kannada cinema was gaining notoriety nationally and worldwide, Puttanna Kanagal emerged as a filmmaker who brought a new, disruptive flair to mainstream cinema. His films often had female leads and focused on women-oriented stories, discussing topics taboo in Indian society. Often adapting works of modern fiction writer Triveni, he made subversive storytelling palatable to the general audience. His 1971 film Sharapanjara is one such example, based on a novel by Triveni of the same name.

Kanagal got his start in the Malayalam film industry and made his Kannada directorial debut with ‘Belli Moda’ (another adaptation of Triveni) which won him the Karnataka State Film Award for Best Film. His films were socially oriented and won both critical and commercial acclaim. His films created a bridge between mainstream and alternative cinema, which was one of his trademarks as a director.

After establishing himself in the industry with hits like ‘Belli Moda,’ ‘Kappu Bilupu,’ and ‘Gejje Pooje,’ he released ‘Sharapanjara,’ which won him a National Film Award for Best Kannada Feature and is considered one of the greatest Kannada films of all time.

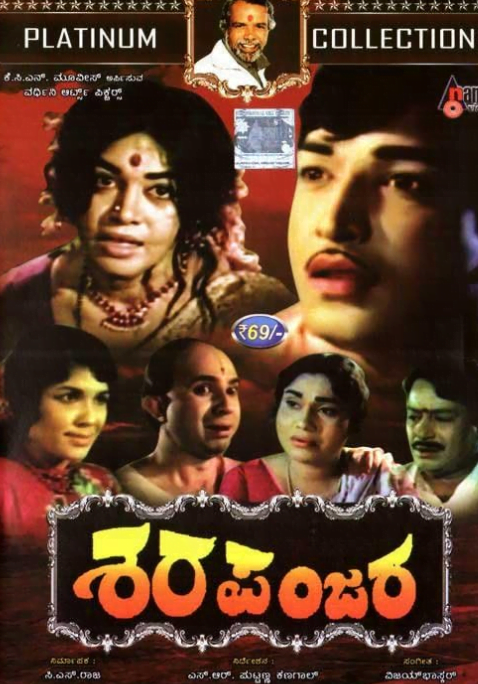

Sharapanjara is a complex story within a simple one– what starts as a typical tale of romance between Kaveri (played by Kalpana) and Satish (Gangadhar), takes a sad turn when Kaveri begins to experience post-partum psychosis. Satish, uncompassionately reacts negatively to her mental state, breaking the once idyllic couple apart.

Adapted faithfully from the original novel, the film provides a broad perspective on the experience and complexities of mental health and trauma. While doing so, it also encompasses a critical depiction of societal stigma, the male ego, and the isolating experience of being ununderstood.

The Unexpected Imperfection of Sharapanjara

Although Kanagal had, by then, established himself as an offbeat filmmaker who addressed taboo topics in his films, Sharapanjara was unique in the sense that its offbeat-ness came out of complete normalcy. Within its three-hour runtime, almost half the film carries out as a simple romance till the entire aura changes. The normal, ideal heroine, Kaveri, upon relieving traumatic memories of assault from when she was younger, combined with postpartum psychosis, transforms completely.

We experience firsthand the isolation that slowly starts to creep onto her through the complete tonal shift between these two halves of the film. While experiencing a severe mental health crisis, she also befalls ostracisation for it.

After her brief admittance to a psychiatric facility for recovery, she finds her life turned upside down, every haven left her side, including her husband. The sudden, unreasonable shift in the attitudes of the people around her– her family, husband, neighbours, and friends– after witnessing their adoration towards her until that point is unfathomable, especially for a modern audience. While depicting this, Kanagal also does the right thing by always backing Kaveri and her feelings. The people around her never receive justification for their behaviour, rather, they come off as confusing and cruel.

Satish, her husband, especially so since his ego gets in the way of viewing Kaveri empathically and undifferentiatedly after learning of her abuse. Amidst all that she is experiencing, she is also put through this trial of moral judgment (for no fault of her own) by the person she is closest to. Moreover, we are made to empathise more deeply with Kaveri because her lack of other support creates a stronger bond between her and the audience.

In creating such an environment, Kanagal aims to raise awareness of the stigma surrounding people experiencing mental health issues. The ignorance of the characters comes off rather as heightened cruelly because of its scale, making us question if it is even fair to be unsympathetic and even ignorant on account of this.

And, by portraying Satish’s response to the abuse of his wife so cruelly, and inhumanely, it gives the audience a template on how to not react in such a situation. While there is a stronger and more prominent dialogue about this now, it was a powerful and rather radical message to send out in the 70s.

The madwoman trope: subverting by representing

Kanagal’s heroines rarely fit the conventional mould of what the ‘woman experience‘ is supposed to be like. Kaveri embodies the often harmful trope of the Mad Woman. The ‘Mad Woman‘ in literature and films is often a woman inflicted with psychological problems shown in an exaggerated and negative light. Additionally, they do not conform to traditional societal expectations and are outspoken about the circumstances around them, making them “difficult” to be around. The film’s tonal shift paired with Kaveri’s circumstances and social treatment push her into this trope.

Even post her recovery– when she seems to have returned to her ‘normal state‘ of being a doting, cheery mother & wife, the lack of social acceptance towards her pushes her to the edge. Despite her continued efforts, people cannot see her individual of her psychosis, and her husband could only view her as ‘tainted‘ after learning of her experience of being sexually abused. All this, coupled with her children being distanced from her, pushes her internal frustration to reach an unbearable limit, propelling her into the madwoman trope.

While more often than not the trope can be harmful, its situational context changes what it means for Kaveri to be portrayed in this light. While she was portrayed as ‘hysterical’ she was never considered irrational. Her hysteria stemmed initially from recalling trauma and later on from social isolation and mistreatment. Her worseningly debilitating state comes to us as a reaction to her immediate surroundings.

At a time when women were discouraged from speaking up against their treatment at home, at a time when women were expected to be subservient, this is a powerful portrayal. To represent a woman standing up for herself was to show the world that women are capable of doing so.

A fated ending

The film ends rather tragically. In a final bout of psychosis, Kaveri is depicted almost as if she has been possessed– the setting and the music take a turn to make the film feel horrific, heightening the effect of her madness. Rather than receiving emancipation from her conditions, the final shot is of her being taken away into a car with a destination unknown but easy to guess. This tragic end to the story of a character we have spent three hours with, whom we have watched not only struggle but also thrive, leaves us angered.

The emotive connection we built with Kaveri over the film’s long runtime enables us to view the end from quite a personal perspective which was perhaps an intentional choice on Kanagal’s part. The film, combining realism with melodrama, has the double effect of being realistic while also being critical. The tragedy that befalls a beloved character turns us to see most clearly that it befell her because she was let down.

Even with its realism and misfortunate ending taken into account, Sharapanjara, among other Kanagal films, was both incredibly socially impactful and left a lasting mark on Kannada cinema.

About the author(s)

Spoorthi is a material feminist, academically rooted in cultural studies. She enjoys analyzing films and applying feminist critique to media & media structures.