I have long been a lover of cinema and there is so much to love about it. It is such an accessible art form and has built a community feeling around itself, making the experience of watching a film more than just passively watching it. And as much as that is true, it is equally true that watching films as a woman is an uncomfortable experience. Not to say that the overarching experience of watching films as a woman is uncomfortable but that when paid attention to, the way that most films are just does not sit right with me.

I was re-watching the 1990 Martin Scorsese classic Goodfellas last year and while enjoying myself and appreciating its humour, its storytelling, and the beautiful shot of Paul Sorvino slicing garlic, it was so very uncomfortable to witness how the film’s only female protagonist (which I would still say is a loose thing to call her), Karen Hill, was being treated. And when I finished watching it, it was all that had stayed with me. Ray Liotta’s Henry Hill, being a member of the mafia and all, is an abusive husband who continually cheats on Karen (played by Lorraine Bracco), a woman whom he chased aggressively to pursue.

Granted that Goodfellas was based on real-life events and real-life people and thus is a story that needs to be represented as genuinely as possible, it also cannot be ignored that it is unnerving to watch a woman be treated like this. It is especially so because characters like Karen are often the only women on screen and on top of which they barely have a stake of their own in this story.*

What matters at the end of the day is what message a film sends out, what narrative it projects, and what audiences it reaches. When thought of from that perspective, and further clubbed with the hoards of films like itself– featuring macho masculinity and criminally underrepresenting women– it becomes a little scary to think about what kind of narratives start to form inside the minds of young boys and men.

On a very separate end of the spectrum, there exists a film like Mary Harron’s American Psycho (2000) which, while a film about a serial killer who murders women, aims to portray the fragility of the male ego and, is one of the most smartly written commentaries of our time. When looked at from the perspective of the writer-director depicting the other gender, how this differs from Goodfellas is that Harron goes in the right direction by critiquing and portraying men from an outsider’s standpoint rather than keeping the gendered perspective absent. It is a feminist film.

Weirdly enough, it gets misrepresented into the very category it aims to comment on. I suspect that perhaps it is so because American Psycho exists within a larger culture where men being this way is a norm. It has to come into question that something must probably be wrong when we live in a world where films from the male perspective are so much the norm that even subtle subversion gets miscategorised into the very thing it is criticising.

Now the thing is that both Goodfellas and American Psycho pass the Bechdel test, which is the bare minimum. And spite of it being the bare minimum and also not necessarily a great measure of feminist representation, it is still such a hard test to pass. The bar is as low as just needing a film to have one scene where two women need to talk to each other about something unrelated to men it is somehow still so hard for most films to pass the test.

A report by Film Companion projected that in 2022 less than half the films released in India that year passed the test. The same report also showed that a measly 12 per cent of heads of departments across the industry– spanning writing, directing, editing, production, and cinematography– are women (with the number standing at an even lower 10 per cent the previous year).

Last year, I set out on the expedition to watch every film on British Film Institute (BFI)’s ‘Directors,100 Greatest Films of All Time,’ which is a list curated by BFI’s Sight and Sound Magazine through a poll conducted amongst almost 500 of the world’s best directors. To no surprise, I noticed that the list had all nine films (out of 104) that were directed by women. Even if unsurprising, that is a staggeringly low number. If we live in a world where women rarely get to tell their stories, of course, it will be so that women’s stories are barely gotten right.

And subsequently, unfortunately, women barely get to see their stories gotten right. So, not only as a feminist but as a woman, it gets difficult to acknowledge and see that it is so. While it is undeniably true that there has been change and there will be change, the slow pace of said change is frustrating to sit through. It is impossible to watch a film in isolation.

It is impossibly uncomfortable to have to appreciate Quentin Tarantino and his cool cinematography and cool title cards and (occasionally) funny jokes when two seconds later I am bound to witness something incredibly objectifying and male gaze-y or Cameron Crowe’s ethereal filmmaking and the perfect soundtrack for what it is sixteen-year-old Penny Lane is manic pixie dream girl to fully grown men.

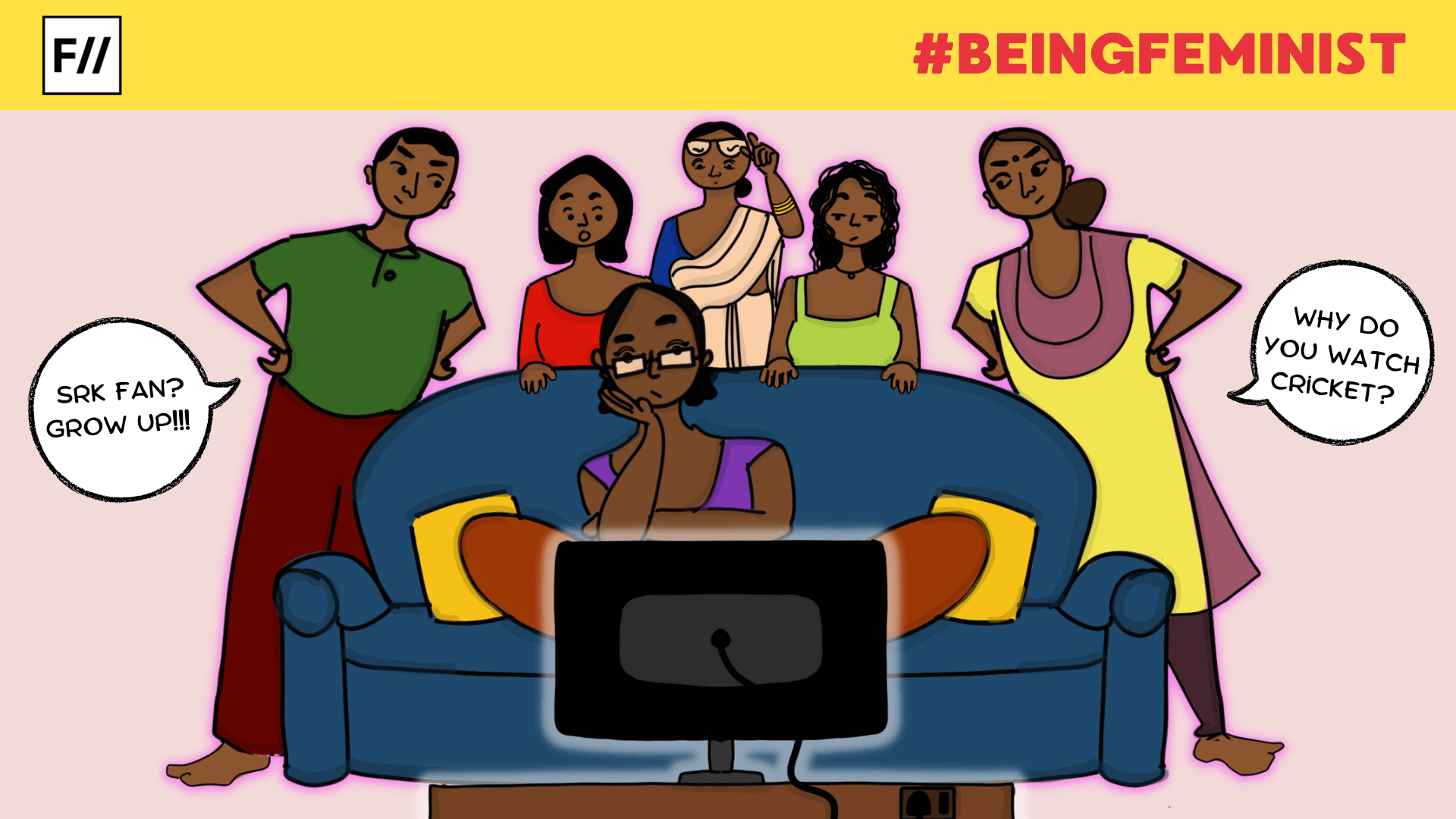

I could write ten more such lines about ten more such directors which makes being a self-appointed ‘lover of cinema,’ sometimes feel like such an unfeminist experience. But now whether or not there are feminist films, as an audience member, my feminist perspective will be perpetually present.

I am a feminist not because at some age due to some factors, I chose to be. I am a feminist because that is the only way I know how to be– it is a choiceless tag that I am more than happy to carry. There is no way, for me, to view a film in isolation, to approach conflicting nuances without seeing them from my point of view as a woman, taking my lived experiences (and that of others around me) into account. And as long as there are people on our end, expecting better of our filmmakers, one can hope, that our filmmakers will strive to do better.

*Although, it is appreciable that Scorsese did try to give Karen’s character autonomy and power, while making her one of the few female characters portrayed in such films, to stand her ground. I also especially love the shot where she– not to condone violence but– picks up a gun and holds it to Henry’s face while atop him which is just excellent cinematographic storytelling.

About the author(s)

Spoorthi is a material feminist, academically rooted in cultural studies. She enjoys analyzing films and applying feminist critique to media & media structures.