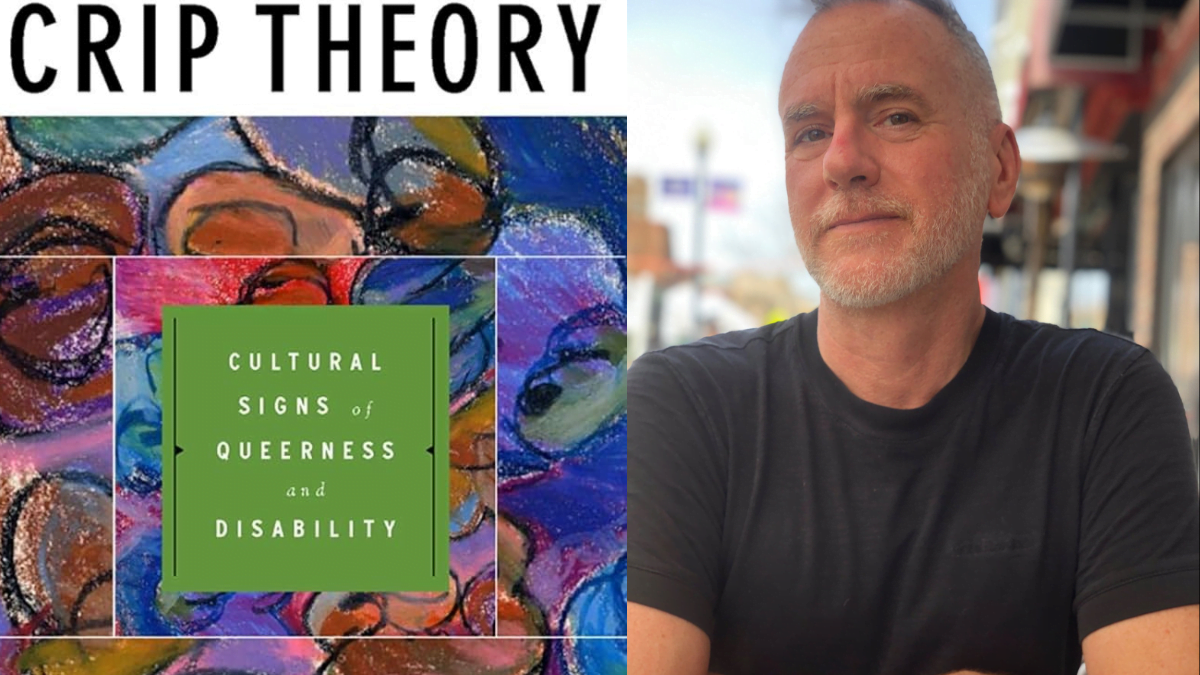

Robert McRuer’s Crip Theory (2006) skillfully combines queer theory and disability studies, thoroughly centring queer and disabled perspectives. The theory not only surveys the “institutional sites” where compulsory able-bodiedness and heterosexuality are produced but also posits that the social norms around compulsory able-bodiedness are very much connected to the social norms around heterosexuality.

The Crip theory is firmly rooted in feminist disability studies which have continued to reveal not just how society is created by and for men but also how society is created by and for the able-bodied. It also draws from queer theory’s radical questioning of the status quo as well as the common pathologisation faced by queer and disabled communities.

Reclaiming the ‘Crip’ Identity

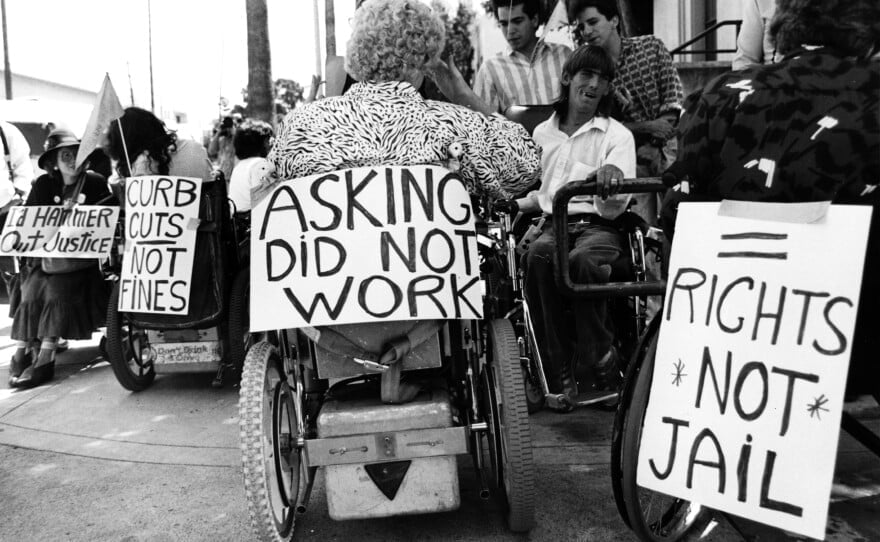

The term ‘crip‘ comes from the word ‘crippled‘ which has historically been used as a derogatory term for disabled people, especially people with some form of movement or motor disability. The word was often used to denote disdain or ridicule towards people with physical impairments.

McRuer observes that the meaning of ‘crip‘ expanded greatly in the late 20th and early 21st centuries in activist, artistic, and theoretical contexts.

Over time, part of the disability movement has attempted to reclaim the term ‘crip‘ as a marker of proud and defiant identification. This comes from the culture of marginalised communities re-purposing derogatory words, which have historically been used to oppress and degrade them, such as the reclamation of the term ‘queer’ by the LGBTQIA+ community.

It is important to keep in mind that like any other community, the disabled community is quite diverse, and not all members of the community might be comfortable using the ‘crip‘ identifier.

How does compulsory able-bodied heterosexuality function?

McRuer argues that able-bodied heterosexuality has been naturalised and codified into the way our society functions. The invisibility of able-bodiedness makes it even harder to criticise this status quo, he maintains. The assumption that heterosexuality is the natural relation of the sexes, or that able-bodiedness is the absence of disability, has long reduced queerness and disability to be seen as a sort of lack, or a deficiency.

Addressing these dilemmas, he puts forth the concept of compulsory able-bodiedness as part of crip theory, alluding to feminist writer Adrienne Rich’s idea of compulsory heterosexuality. Hence, the system of compulsory heterosexual able-bodiedness surrounding us emanates from “everywhere and nowhere” simultaneously.

“Able-bodiedness, even more than heterosexuality, still largely masquerades as a nonidentity, as the natural order of things,” writes McRuer. Ableism is elusive, for it pervades the languages we use and the ideological spaces that we inhabit. This culture assumes that everyone, including persons with disability, will uniformly prefer and strive for able-bodied identities and perspectives.

He uses the example of academic Micheal Berube’s memoir about his son Jamie who lives with Down syndrome. Berube mentions that the conversations that he has with other people about Jamie often employ a common subtext, one that asks Berube if he is not disappointed to have a child with a disability.

McRuer contends that other kinds of disabled bodies are also often interrogated with questions carrying a similar subtext – “In the end, wouldn’t you rather be able to hear/ not be HIV positive/ be more like me?” Ableist culture also demands that there be an unflinching affirmative answer to these questions.

It is the introduction of this kind of normalcy into the system that creates compulsion. Because everyone wants to fit in, this compulsion to be ‘normal‘ is effectively hidden by the appearance or the illusion of choice, whereas in reality, there is no choice.

The theory also posits that compulsory able-bodiedness and compulsory heterosexuality are interwoven in myriad ways. For example, McRuer takes excerpts from queer theorist Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble and argues that the same framework can be applied to the ableist hegemony as well. Butler’s work proposes that heterosexual hegemony is sustained due to its constant performativity and endless repetition of itself.

In the context of disability studies, the emphasis on identities constructed through repetitive able-bodied performances is even more – “think, after all, of how many institutions in our culture are showcases for able-bodied performance,” McRuer notes.

Crip Theory and the 70-hour work week

A prime example of an institution being a “showcase for able-bodied performance” is the Indian workspace which is heavily designed and managed around heterosexual able-bodiedness. Recently, Indian businessman Narayana Murthy reportedly said that young people in India should be working 70 hours a week to contribute to the nation’s progress. This translates to roughly 12 hours a day, for 6 days a week.

In the 21st century, the six-day work week has increasingly become obsolete in the face of an eight-hour, five-day work week (40 hours per week in total). Newer research has shown that multiple benefits come with organisations switching to a four-day work week.

So in addition to being exploitative towards even non-disabled people, the 70-hour work week assumes that the population is compulsorily able-bodied and inhabits a heteronormative, able-bodied family form with fixed gender roles.

It not only assumes that there is someone in the family specifically dedicated to caregiving duties, but also that all bodies are uniformly productive all the time. Therefore it discredits the perspectives of queer and disabled bodies as well as family forms, by not taking into account their lived experiences.

The multi-faceted nature of Crip Theory

McRuer’s work examines the phenomenon of coming out as crip, akin to the notion of coming out as queer. It situates crip theory in relation to disability and LGBTQIA+ identity politics and their ideas of accessibility. It also offers queer critiques of marriage and domesticity.

Additionally, the theory focuses its attention on the politics of pedagogy and academic labour in educational spaces, “I identify the ways in which the cultural demand to produce students who have measurable skills and who write orderly, efficient prose, is connected to the demands of compulsory heterosexuality/ able-bodiedness that we inhabit orderly, coherent identities.” It provides structures to be able to resist these systems and position queerness and disability as desirable.

Crip theory delves into the financial and media institutions that disseminate “marketable images of queerness and disability.” Through an analysis of pop culture artefacts, including films like As Good As It Gets (1997) and Titanic (1997), the television series Queer Eye for the Straight Guy (2003), and American artist Bob Flanagan’s performances, it constructs the process of ‘cripping.’

This, in turn, aims to resist normativity – “Cripping offers a critical process, considering how certain bodily or mental experiences, in whatever location or period, have been marginalised or invisibilized, made pathological or deviant.”

McRuer contends that institutions of compulsory able-bodied heterosexuality perpetually work to reproduce themselves. But because these institutions depend on queer or disabled people’s existence to position themselves as superior, able-bodied heterosexual hegemony is always in “danger of collapse.” He intends for crip theory to transgress these delimitations “by setting up counter-hegemonies that celebrate the weak, deviant, sick, and perverted instead of the healthy and the normal.”

About the author(s)

Divyani is a media and research professional with a background in critical cultural theory. Her core interest areas are digital cultures, sexuality, and mental health. She loves annoying her cat and a good cup of coffee.