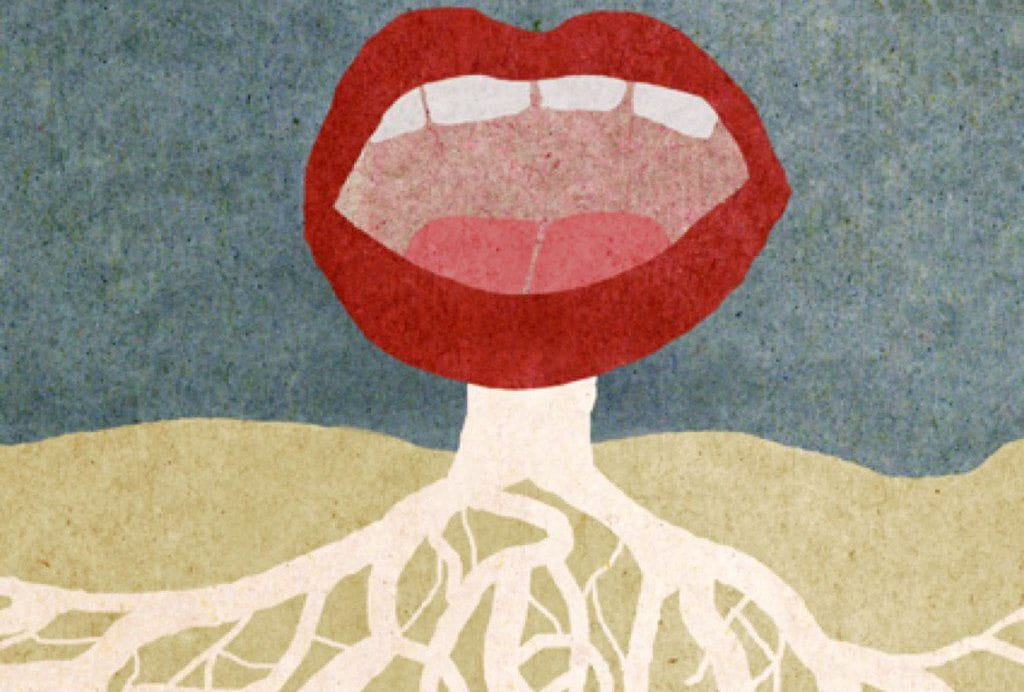

“Language is the house of Being. In its home man dwells,” writes Martin Heidegger. The same language that shelters the crowd defines the thresholds for marginalised communities – silencing them. Language is born out of necessity. The home that was built by the mainstream found no necessity in making space for the non-normative.

In the lack of words for diverse genders or sexualities or related social acts – a language limits access and expression of the queer communities. One of the metaphorical bricks thrown at this language barrier is the east-Indian language – Ulti. A complete language with words created by the community, for the community – whose tongue is Ulti?

In the Mughal court, the Hijra or Khwaja sera community (eunuch community) were the blessed protectors of the royal family. While they had a legitimate space in Indian society created and justified by Indian mythology – the community wove their web of language from existing ones to have a secret and exclusive communication medium. There were a few regional varieties of this language – Gupti or Ulti and Hijra Farsi being the most prominent. This language became even more important when the British ships docked at the Indian port. The binary worldview of the West clashed with the Indian traditions.

The controversial Criminal Tribe Law enacted by the East India Company in 1871 targeted certain caste groups as “hereditary criminals.” Their incomprehension of the Indian third gender resulted in the eunuch communities being victims of this law. Under increased surveillance and threat of castration, the secret language family became a refuge for the traditional eunuch communities.

From the guru the language is passed onto the chela

Historically anti-languages evolved in the underbelly of the mainstream. Polari, Gobblydock or Thieves’ Cant are some of the old languages from that world. Amongst them, Polari– originally borrowed from Italian, the gipsy Romani and criminal cants, came to be known as queer language in 20th century UK. Many such anti-languages have continued to evolve and thrive.

Ulti continues to be the language of the Indian (especially east-Indian) Hijra – Koti community that subverts the mainstream language and encodes it in a secret exchange. The language not only redefines the role of the language but also that of the mother. The mother order in the Hijra community deposes the heteronormative understanding of a mother and traditional family as the social institution.

The reclamation of motherhood by the trans community not only challenges the gendered associations but reappropriates the seat of systemic power within that word.

In their social order, from the guru or the mother the language is passed onto the chela or the daughter. Linguist and Ulti-researcher Dr Enakshi Nandi in a conversation about the order of transmission says, “Fluency in Ulti determines the seniority, and therefore the power and authority of the speaker within the community.” The reclamation of motherhood by the trans community not only challenges the gendered associations but reappropriates the seat of systemic power within that word.

Like hierarchy is a usual element of most language groups, so is solidarity, especially when it is borne out of subversion. In language, solidarity enacts the social proximity between people. The reciprocity of this solidarity equation in a language determines the tonality and content of our interpersonal interactions, from absolutely formal and precise to completely informal and elaborate. While the fluency of Ulti dictates the hierarchy within its speech community, the state of high solidarity ensures the safe and free exchange of the speakers’ thoughts and expressions.

One of the Ulti speakers from Bengal, Ari Ray Chowdhuri says, ‘amar moner kothata bhirer moddhye amar moner ba amar shomogoshthir manusher kache futiye tola,’ (this language lets my deepest thoughts sprout among my peers even in the midst of a crowd). Thus continues the sustained nature of its privateness. The secrecy of this language certifies the community’s persistence in an alienating space – forging intimacy and solidarity.

Dr Nandi’s book, Secrets, Subversions, and the Hijra-Koti Subculture: A Sociolinguistic Analysis of Ulti, brings to light another aspect of the language. When we think of gender-inclusive language, the popular understanding largely relies on certain terminology to sustain gender-specific identities, mainly limited to nouns and pronouns (he, she, they, trans, cis, and more).

However, for years, sociolinguists have studied languages worldwide to encode gender beyond mere nomenclature. For example, in the 1929 work of Benjamin Sapir, we find examples of the Yana from California, where the speakers used special speech forms when the speaker or the addressee was a woman. Similarly, in the Koasati from Louisiana, male speakers add an ‘s’ at the end of most of their verbs signifying their social identity as men.

Ulti’s ability to encode expressions

A similar phenomenon has been attested by Dr Nandi in the Ulti. The grammar frame of the Ulti variety comes from Bangla since it is the language that the majority of the Ulti speakers grow up with. However, Bangla does not have the provision to reveal the speaker or the addressee’s gender identity, not in the pronouns or any common nouns.

Dr Nandi says, ‘There is a secret and specialised vocabulary that has developed within the community because there are linguistic gaps in the mainstream dominant languages that did not capture the details and nuances of the transgender experience.’

Ulti speakers have over time developed a marker to accord gender to any noun. In the words of Dr Nandi, ‘In this language, any noun, from “telephone” to “man” to even “health” can be pronounced with a symbolic (feminine) gender marker.’ The striking nature of this phenomenon lies in the fact that by adding this gender marker, the Ulti speakers are not trying to associate any gender with the object itself, but they are asserting their own identity of belonging to their adopted Hijra-Koti community.

The relationships established in the Hijra-Koti community and by extension within the Ulti are also predominantly feminine – mothers, daughters, sisters, aunts and so on – a female kinship system. The masculine or marital relations nouns are conspicuous in their absence from the language – a dispensable expression in the world of Ulti.

Despite the diachronic need for Ulti to have formed as a language protecting the existence of its speakers, its kindred spirit is apparent. Born into the Bangla speech community (majority of the Ulti population), language is not a choice they have to make. A polyglot from Bengal who speaks six languages, Tara shares her experience of learning this language, ‘Jobe thheke ami thheek thhaak bangla bhasha bolte pari shei tokhon thheke.’ (From the day I started speaking Bengali I have been speaking this language).

All languages co-exist, Ulti is merely one of the many languages the community speaks. The only difference, she points out, remains in the language’s ability to encode expressions that she does not feel comfortable sharing with the outside world. ‘Ami amar Koti bandhobider shathe kotha bolar shomoy Ulti use kori.’ (I speak in Ulti with my Koti girlfriends)

Since its inception, Ulti has provided security to the speakers from social persecution. Hence the community has been extremely protective of the language. Outsiders are not invited to speak it unless exclusively given an entry due to close allegiance.

From sharing secrets to expressing desire, Tara spoke about the freedom Ulti gives her and her friends to safely and unashamedly speak in public. Since its inception, Ulti has provided security to the speakers from social persecution. Hence the community has been extremely protective of the tongue.

Outsiders are not invited to speak it unless exclusively given an entry due to close allegiance. Tara expressed her concern with the language being available to people, ‘Ami chaina Ulti bhasha shobai boluk… bhasha ta shudhu amader.’ (I do not want this language to be spoken by everyone… this language is exclusively ours.)

Redefining the idea of a mother tongue

Beyond its combination of power and solidarity, Ulti provides its speakers with a world where they can express what matters to them. Language varieties are commonly formed due to their speakers’ specific needs. Unlike most prominent languages dictated by a convention-driven understanding of human bodies, the Ulti community has specific vocabulary to talk about their bodies outside of common parlance.

Survival has given rise to distinct income patterns which have their nomenclature within the community, such as Dr Nandi points out that they have separate terms to denote whether they are performing at a ceremony, begging, or performing sex work.

Over time, education and information in the community have given rise to a strong sense of pride in Ulti, a language they shield from outsiders. Today, many speakers want the world to know about this prized possession without disclosing its build. Some even proclaimed it on social media by saying “Ulti bhasha amar matri bhasha,” (Ulti is my mother tongue) on February 21st. They redefine the idea of a ‘mother tongue’ by embracing this chosen language like an adopted child.

The chosen trans-family, with its chosen tongue, built on alternative relationships – paints a euphoric picture of a queer home. In the warm embrace of Ulti, its mothers and daughters find kinship, validation, and laughter with friends. In the words of Ari, “bhashar moddhye theke amra jeno bhalo thaki,” (let us stay happy nestled in our language).

About the author(s)

She/they is an editor and illustrator from the suburbs of Bengal. A student of literature and cinema, Sohini primarily looks at the world through the political lens of gender. They uprooted herself from their hometown to work for a livelihood, but has always returned to her roots for their most honest and intimate expressions. She finds it difficult to locate themself in the heteronormative matrix and self-admittedly continues to hang in limbo