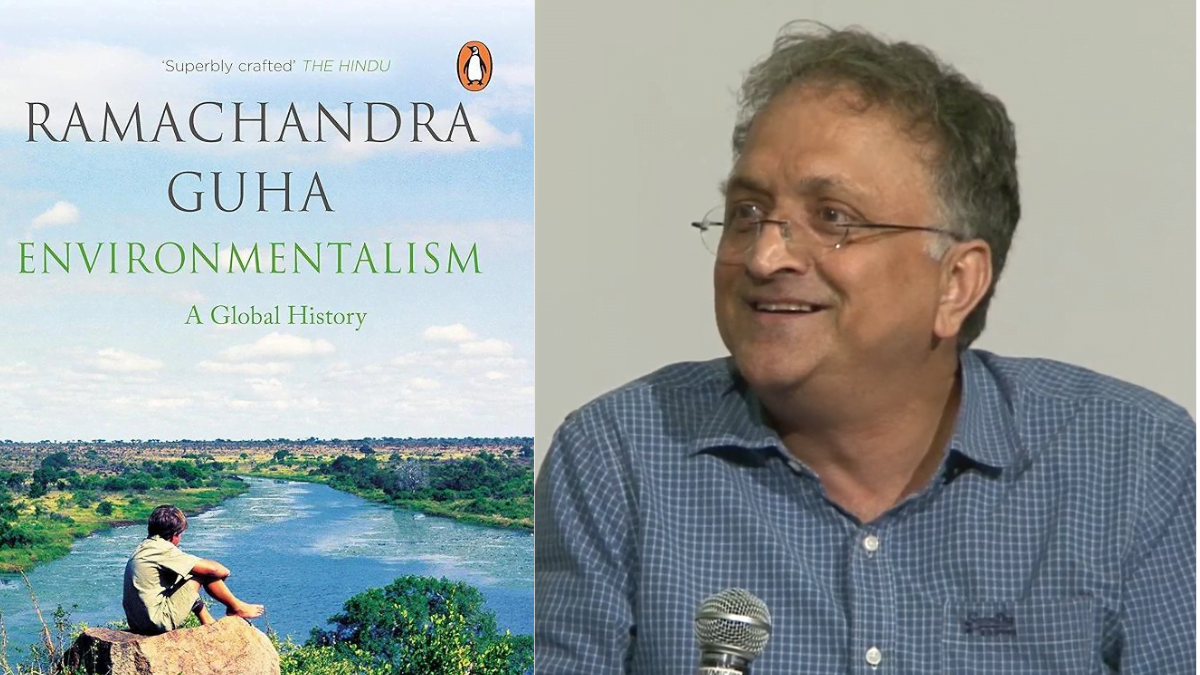

Ramachandra Guha, a distinguished historian, and biographer based in Bengaluru, specialises in a wide range of research domains such as social, political, contemporary, environmental, and cricket history. His work, Environmentalism: A Global History, published in 2000, stands out as a precise and easily accessible read. In addition to this, Guha has contributed significantly to the field of environmental studies through works like The Unquiet Woods (1991) and The Use and Abuse of Nature (1995).

Environmentalism: A Global History serves as a gateway for readers to explore the concept of global environmentalism.

Environmentalism: A Global History serves as a gateway for readers to explore the concept of global environmentalism. The book’s research and inception coincide with a crucial period in history, the 20th century that was characterised by the opening up of the global market; the adoption of neo-liberal policies, and the ascendancy of the capitalist notion of “development”, making the book a timely and insightful exploration of environmental issues.

The book meticulously examines the emergence of environmental movements on various continents, exploring the detrimental consequences of unchecked development on the natural world and its resources. Structured into two parts, the book navigates through the initial and subsequent waves of environmentalism. The overarching goal is to foster a transnational understanding of the environmental discourse, tracing the roots of environmental movements across various cultures.

Part I: environmentalism’s first wave

The first half of the book unfolds the origin and the evolution of the first wave of environmentalism, spurred by the swift pace of industrialisation. Industrialisation led societies to incessantly exploit nature, seeing it as a convenient source of inexpensive raw materials and a convenient disposal site for the byproducts of economic progress. While the industrial cities were the prime cause of pollution, its ramifications were most acutely felt in rural areas and colonies. Guha writes, ‘Nature became a source of cheap raw materials as well as a sink for dumping the unwanted residues of economic growth.’

Guha contends that the environmental movement has compelled people to reconsider the rights of nature. Through his exploration, he underscores the intricate dynamics within environmental movements—complete with stakeholders, oppositions, allies, and those who remain on the fence.

Through his exploration, he underscores the intricate dynamics within environmental movements—complete with stakeholders, oppositions, allies, and those who remain on the fence.

Guha categorises responses to the initial wave of environmentalism into three main streams: the back-to-the-land movement, scientific conservation initiatives, and the promotion of wilderness ideas. Firstly, the back-to-the-land movement serves as a moral and cultural critique of the Industrial Revolution. Guha intriguingly links the works of romantic poets with Gandhian ideology, while also navigating through the controversial association between Nazis and the Green movement; he further expounds to discard the relation between the two.

The scientific conservation initiatives were intended to advocate for the judicious use of resources, promoting a more sustainable approach. Guha posits that this approach, unlike romanticising an idealised past, seeks to reshape the present through reason and science. Drawing on Marsh’s Man and Nature, Guha writes, ‘It did not hark back to an imagined past, but looked to reshape the present with the aid of reason and science’ (p. 43).

The third response, the promotion of the wilderness idea was aimed to safeguard the untouched areas of nature from human intervention. Guha explores the historical practice of sacred groves as an ancient manifestation of the wilderness idea. He exposes colonial hypocrisy by highlighting how colonialists initially exploited nature and hunted extensively, later introducing conservation concepts built on racist foundations. In the afterword of the first section, Guha introduces three eminent figures- Geddes, Mumford, and Mukherjee—who defy easy categorisation within the aforementioned categories. He recognises them as ‘forerunners of the ‘inter-disciplinary’ and ‘trans-disciplinary’ intellectual movements of the present-day,’ illustrating their contributions to the evolving landscape of environmental discourse.

Part II: environmentalism’s second wave

The second part of the book begins with a thorough examination of the post-World War II landscape, concerning environmental degradation. Guha calls the twenty years after World War II, the ‘age of ecological innocence.’ This section meticulously traces the origin of the second wave of environmentalism, emphasising the significance of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in fostering an environmental consciousness. Moreover, within this section, Guha draws attention to the parallels between environmental movements with various other social movements. By illustrating these connections, he underscores the interconnectedness and shared objectives of environmental advocacy with broader societal concerns, further enriching the reader’s understanding of the contextual complexities that shaped the second wave of environmentalism. However, he points to the lower internal divisiveness in the environmentalist movements in comparison with the other social movements.

Further, the book delves into the distinction between the environmental debate and the environmental movement. On one side, scientists expressed concerns about depleting resources, while on the other, there was a growing fascination with the exploitation of nature. Guha further highlights instances of discriminatory waste dumping, citing the example of Emelle, an Alabama town predominantly inhabited by Black residents, which receives waste from forty-five states.

Moreover, the book explores the significant role of women in preserving nature, emphasising that for them, the health of their children is a non-negotiable priority (p. 122). This section also traces the emergence of the German Greens as a national party in Germany, adding a global dimension to the evolving environmental discourse.

One of the most profound chapters in the book, ‘The Southern Challenge,’ delves into the orientalist perspective of environmentalism, exploring how the Western world perceived the global south as too impoverished to be concerned about environmental issues. Guha effectively challenges this notion by illustrating examples from communities like the Penan community and movements such as the Narmada Bachao Andolan.

Moreover, the book explores the significant role of women in preserving nature, emphasising that for them, the health of their children is a non-negotiable priority (p. 122).

Moreover, Guha skillfully expounds upon the environmental movements of Brazil and India, to adumbrate striking resemblances between the struggle of Chico Mendes and the Chipko movement. The narrative unfolded the less talked about aspect of environmentalism, how the environmentalism of the poor helped redefine development as socially aware, decentralised and environmentally friendly.

Guha’s concluding arguments

Guha in the subsequent chapters, extends the analysis to Second World countries, particularly the Soviet Union, shedding light on how Marxist ideology, centred on conquering nature and prioritising technology, often neglected environmental concerns.

The book’s final chapter takes the readers to the Earth summit, addressing the laxity in environmental discourses, which he calls ‘conspicuous disregard of limits.’ Despite these challenges, he expresses hope for future generations to become more cognisant of ecological issues. The overarching message of the book is that environmentalism transcends national boundaries, and brings people together to address shared concerns and foster a more sustainable future.

The book, however, merely skims through the diverse perspectives and actions within the environmental movement, as Guha labels it, it remains a significant read. It invites the readers to embark upon contemplation regarding environmental deterioration and preservation, guiding them from where to begin. The book serving as an exceptional initiation, offers a foundational standpoint for those inclined to explore the complexities of the environmental crisis and engage in environmental stewardship.