‘When I’m walking down the streets, I don’t see people anymore, I see skeletons walking, their eyes empty, starving, grieving, and scared…’ says Hossam Shabat, a journalist from North Gaza.

Journalists in Gaza prevail, and so does the genocide. In the past month, the word “famine” has breached the news headlines, even though Gaza exceeded the 20% acute food shortage threshold back in December.

Threats of famine, which were cautioned against during the ICJ case, have materialised with all but meager airdrops for aid.

Threats of famine, which were cautioned against during the ICJ case, have materialised with all but meager airdrops for aid. Even though the crisis is escalating, IPC is uncertain which entity is authorised to declare a famine. Although Israel continues to use mass starvation as a political weapon, Gaza is reported on as a region teetering on famine for weeks now, simply because there are debates about who can declare a famine.

In the past six months, the international community has failed to create any meaningful humanitarian intervention in Palestine. A UN official explained, ‘Once a famine is declared, it is already too late for too many people.’ While that is true, what with the contention around the appropriate authority who can declare a famine in Gaza, it is probably already too late for too many people.

The declaration of a famine comes with a change in the language used to report on the genocide. It may not force an official resolution. But it will bring more urgency and pressure to impose a lasting ceasefire.

But, while the starvation campaign escalates, international complacency and Israeli military tactics reveal the enduring legacy of colonial biopolitics shaping the future of Gaza.

Colonial biopolitics

Biopolitics, according to French philosopher Michel Foucault, discusses how the government creates policies to control human bodies. Colonial biopolitics recontextualises that theory to explore how colonial bodies are transgressive. In settler-colonial states, biopolitics can be executed through medical and welfare institutions — this could come in the form of inadequate healthcare or deliberate restrictions on nutrition, both of which Israel has committed in Palestine.

The apathy among the UN Council, namely the US veto power abuse and the delayed responses to the aid cut-off, is exemplary of a moral neutrality that allows settler-colonial states to thrive.

The concept of ‘state of exception’ in biopolitics, as theorised by Giorgio Agamben, can be used to explain this. Agamben describes this as a period where a state’s natural and cultural habitats are suspended. Viewing this through an intersectional lens, marginalised bodies — Palestinian bodies — are in a continuous state of exception under the occupation. If not completely denied rights, their quality of healthcare and legal order is significantly diminished.

These ideas are not only evident through the actions of the Israeli government but also through international law. The apathy among the UN Council, namely the US veto power abuse and the delayed responses to the aid cut-off, is exemplary of a moral neutrality that allows settler-colonial states to thrive.

By reframing Zionism as a decolonial ideology meant to resist anti-semitism rather than a colonial project, Western governments offer moral neutrality to Israel, which neither prohibits nor obligates any ethics to the occupation. And so, mass starvation becomes the product of moral neutrality and colonial biopolitics.

Past famines

The Gaza Strip famine will not be the first famine where biopolitics influenced the response to and documentation of a catastrophe. Because of how the international law is structured, it grants excess power to imperialist nations and the current state of Gaza parallels the famines of the British Empire.

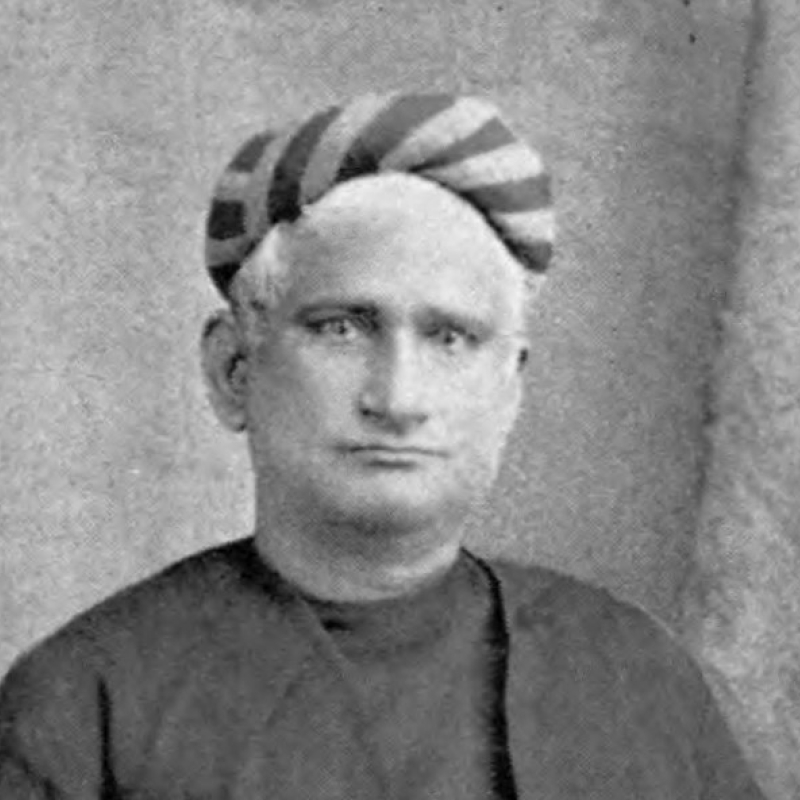

Like the current situation, the Great Bengal famine deliberately starved people. It was carried out systematically to subjugate Indians. Senjuti Mallik, who analysed the Bengal famine through a biopolitical lens, explained that the British viewed Indian bodies discursively. Rather than viewing populations as a coexistence of humans, biopolitics views the population as a means to achieve the state’s objective in a political economy. It transforms a famine into a tool to sustain the empire. So, the Bengal and the current Gaza famine are examples of how imperial nations use biopolitics to subdue resistance.

So, the Bengal and the current Gaza famine are examples of how imperial nations use biopolitics to subdue resistance.

It is easy to detect the parallels between the language used by the British Empire, and Israeli officials. ‘We are fighting human animals, and we are acting accordingly,’ said Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant. ‘There will be no electricity and no water [in Gaza], there will only be destruction,’ Maj. Gen. Ghassan Alian said. The dehumanisation of Palestinians into ‘animals’ is similar to Churchill’s description of Indians as ‘beastly people.’ Not only is colonial language incendiary, but it also reinforces biopolitics to justify the occupation.

Gaza: an open-air prison

It is hardly surprising that under current circumstances, many Gazans describe their home as an ‘open-air prison’. They are forced to depend on Israel for all necessities of life — food, water, shelter — while also operating under a state of exception. Frequent arrests, long prison sentences, checkpoints, and targeted bombings of medical facilities have all led up to today, where Gazan children are experiencing a nutritional decline at the fastest rate in history.

Professor Jasbir K. Puar explores the imperial biopolitics of Israel in her book, The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability. She explains that Israeli policies towards Palestinians designate them ‘available for injury.’ The current famine is an expansion of that ‘right to maim.’

Children continue to die from malnutrition in Kamal Adwan and Shifa hospitals. The illusory US maritime aid plan discounts Israeli responsibility, or the lack thereof, in aid distribution. Palestinians are politically and anatomically obscured from not only the Israeli government but also international law. Their injuries and starvation are revised to maintain a morally neutral image of the international committee. The proposed maritime aid plan exemplifies the biopolitics of food provisioning. Starvation in Gaza is not out of scarcity of resources but the abundance of restrictions, cumbersome inspections of aid trucks, and unpredictable bombings of aid routes.

Mythologising the famine in Gaza

A famine — manufactured or not — enables imperial governments to remove accountability. This is where colonial biopolitics thrive. There isn’t killing, there’s merely dying. It introduces a passivity to genocidal violence. It is an omission of guilt — an expansion of moral neutrality.

A famine — manufactured or not — enables imperial governments to remove accountability. This is where colonial biopolitics thrive.

In the past few months, we have seen how Western media outlets often gloss over the debilitating situation in Palestine by exchanging words like ‘children’ for ‘minors’ and ‘killing’ for ‘dying.’ With Western media already skewed in Israel’s favor, a famine adds to the perception of spectral violence in Palestine.

If the desperately needed ceasefire is implemented and aid trucks finally, adequately support Palestinians, it is not the end. Soon, we will see a revisionist history of this genocide and famine. We have witnessed the rewritten accounts of colonial famines. Colonial biopolitics continue to distort the narratives of oppression even after the end of an active conflict.

Rather than losing the history and present of the Palestinian struggle to Western revisionism and biopolitics, we need to offer our resistance as a promise that we renew every day to honor the martyrs of Palestine. Biopolitics is not just a struggle between governance and human bodies but also a struggle between history and forgetting — of policies, language, and the people searching for a world that humanises their struggle.

Very interesting analysis. Keep up the good work!

Loved the parallels drawn between Gallant and Churchill!