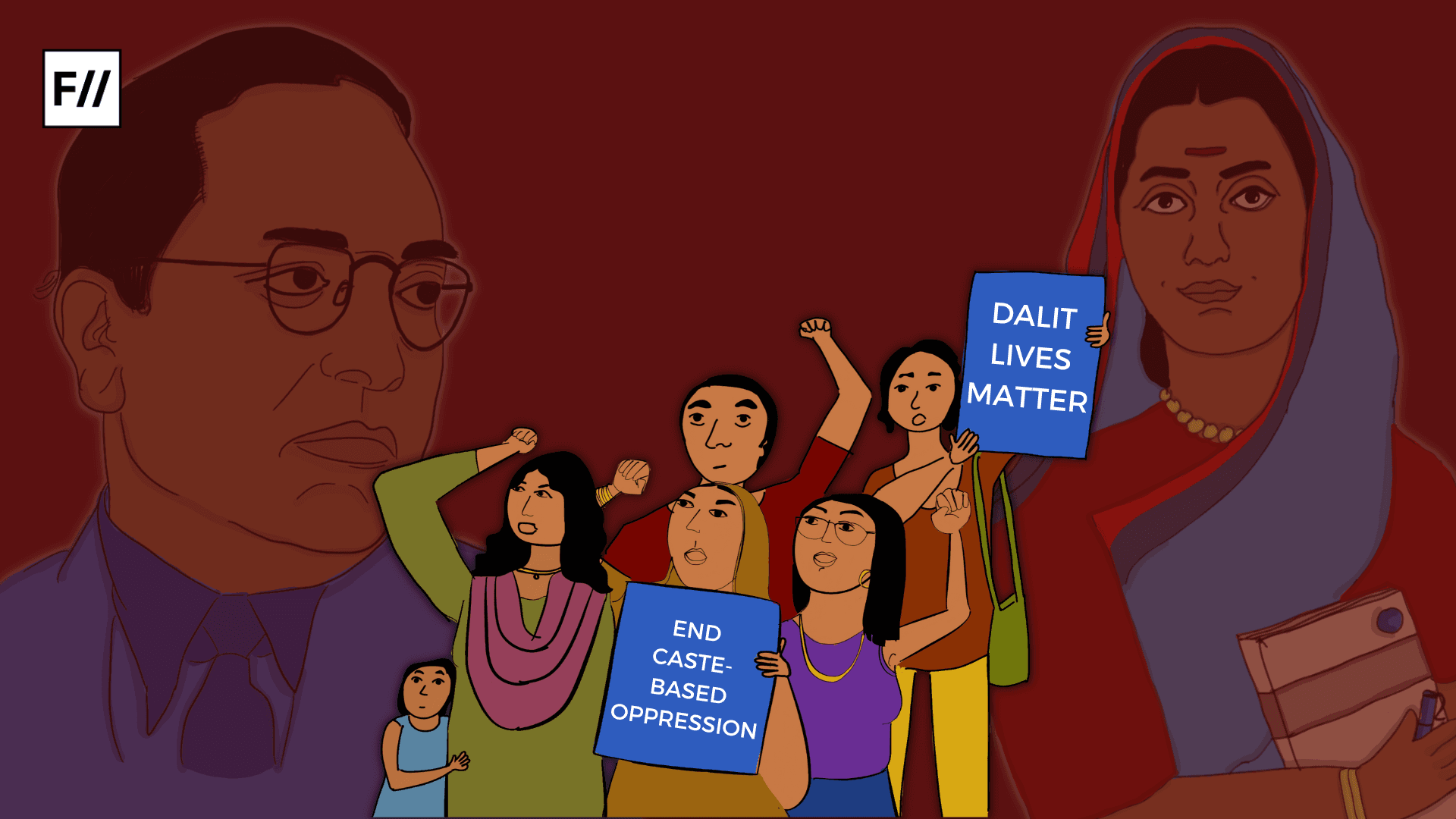

The recent revelations from the Ambedkar, Periyar, Phule Study Circle (APPSC) RTI data regarding the denial of 132 PhD seats for Scheduled Caste (SC), Scheduled Tribe (ST), and Other Backward Castes (OBC) students at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi (IIT Delhi) serve as a glaring reminder of the persistent challenges in achieving equity and inclusivity within higher education. This data, obtained through a Right to Information (RTI) request, underscores the systemic barriers faced by marginalised communities in accessing educational opportunities.

On Wednesday, March 6th, concerns were raised on the microblogging platform X formerly Twitter regarding alleged violations of reservation norms at IIT Kharagpur. The student group highlighted accusations of the institute flouting regulations in both faculty recruitment and PhD admissions, despite directives from governmental and judicial authorities, as recent as 2023.

This concerning data report sheds light on fundamental flaws within our educational system, which should ideally serve as a nurturing environment for aspiring individuals. Instead, it exposes a landscape marred by systemic inequities and failures to uphold principles of fairness and inclusivity.

In light of these revelations, we are compelled to ask ourselves: do our educational institutions truly serve as spaces where dreams can flourish without discrimination or hindrance, or who will answer the pressing need for comprehensive reforms to uphold their integrity?

Examining the RTI Data: SC/ST/OBC representation across IITs

According to the RTI data, out of 4,226 SC, ST, and OBC candidates who applied for PhD admission in the academic year 2023-24, only 203 students were selected. This staggering discrepancy in the selection process raises serious concerns about the fairness and transparency of the admissions process at IIT Delhi. Furthermore, the revelation that four departments within IIT Delhi did not grant admission to a single candidate from the reserved categories underscores the institutional challenges in promoting diversity and representation.

Earlier this year, APPSC made claims, backed by RTI responses, alleging violations of reservation policies at IIT Delhi and IIT Kanpur. These allegations pertained to PhD admissions at IIT Delhi and faculty recruitment at IIT Kanpur, the report said further. As per the report, a January 2024 RTI data highlights concerns about imbalances in faculty composition at IIT Kharagpur. Out of 742 faculty members, a striking 92 per cent (683 individuals) belong to the General category. In comparison, only 5.4 per cent (40 members) are from the Other Backward Classes (OBC), while the Scheduled Caste (SC) category represents a mere 2.3 per cent (17 members).

Shockingly, the Scheduled Tribe (ST) community is notably underrepresented, with just two faculty members, comprising a meagre 0.27 per cent of the total. Additionally, among the 683 General category faculty, two individuals are from the Economically Weaker Sections category, exclusively open to non-reserved castes.

Furthermore, the data revealed that out of the 45 departments at IIT Kharagpur, a striking disparity exists: 43 departments lack any faculty members from the Scheduled Tribe (ST) community, while 32 departments have no representation from the Scheduled Caste (SC) category. Additionally, 23 departments lack any faculty members from the Other Backward Classes (OBC) community.

Surprisingly, according to the report, out of the 101 faculty members hired by IIT Kharagpur last year, only two were from the Scheduled Caste (SC) community, while 10 belonged to Other Backward Classes (OBCs).

Similarly, regarding PhD admissions for the academic year 2023-24, out of the 345 students admitted by IIT Kharagpur, 182 were from the General category. Meanwhile, 46 students (13.3 per cent) were from the SC category, 9 students (2.60 per cent) were from the ST category, and 82 students (23.7 per cent) were from the OBC category.

Dropout patterns: The unresolved challenge for marginalised students

According to a report that came out a few months back, Over the past five years, 13,626 students belonging to the historically marginalised Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and Other Backward Classes (OBC) have discontinued their studies at central universities, Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), and Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs).

With this alarming trend being a concern, during its June meeting, the IIT Council addressed the issue of student dropouts. In response, IIT Madras suggested introducing a sports quota for students, complementing existing programs across the IITs that permit students to exit their courses with lesser qualifications.

Notably, central universities accommodate a significantly larger number of undergraduate students compared to the IITs, with Delhi University’s undergraduate seats alone surpassing the total available across all IITs, according to the report. Yet the existing casteism and discrimination faced by the students eventually shun their dreams, raising the numbers of the dropout list.

Gender disparity and caste-based discrimination in higher education

Gender disparity is also glaringly evident, with the PhD admission records for the academic year 2023-24, out of 4,226 applicants from SC, ST, and OBC backgrounds, only 203 students were accepted. Shockingly, four departments at IIT Delhi did not admit any candidates from reserved categories. Furthermore, only two female candidates were selected for IIT Delhi’s PhD program in the same academic year.

This highlights broader systemic issues related to gender inequality in STEM fields and the need for targeted efforts to address this imbalance.

According to a recent report, The APPSC’s assertion that IIT Kharagpur is also violating reservation norms in faculty recruitment and PhD admissions, despite government and judiciary orders, adds to the gravity of the situation. This suggests a broader pattern of non-compliance with reservation policies across premier educational institutions in the country.

Moreover, the staggering dropout rates of over 13,500 SC, ST, and OBC students from central universities, IITs, and IIMs in the last five years, as revealed in Lok Sabha data, further underscores the systemic challenges faced by marginalised communities in higher education.

In response to these revelations, Dheeraj Singh, an advocate for diversity in higher education and an alumnus of IIT Kanpur and IIM Calcutta, rightly points out that denying seats based on caste is a form of discrimination that cannot be tolerated. The need for transparency, accountability, and proactive measures to address caste-based discrimination within educational institutions is paramount, the recent reports highlighted.

Despite the establishment of an SC/ST cell and mandates to monitor and evaluate reservation policies, IIT Delhi’s continued violation of reservation norms raises questions about the effectiveness of existing mechanisms in promoting inclusivity and diversity. The APPSC’s assertion that 25 departments did not admit a single ST student last year further underscores the urgent need for institutional reforms to address these systemic inequalities.

The exclusion of SC, ST, and OBC candidates from PhD programs at IIT Delhi, and the wider issue of non-adherence to reservation policies in higher education, underscores the critical need for systemic changes. Ensuring equal access to educational opportunities for every segment of society is not just a matter of policy but of social justice and inclusivity. Until and unless the authorities and the management answer the students in the nation, the gravity of the question remains the same:

How can educational institutions claim to be beacons of excellence and innovation in education if they fail to commit to principles of social justice and inclusivity in their admissions and recruitment processes?