Whenever a controversial issue occurs, the discourse on the position of the person who addresses the issue also comes to the surface. The discourse on positionality is a valid topic to debate especially regarding marginalisation. It refers to the axis of how one is related to the respective identities like race, gender, caste, ethnicity and so on. It helps us shape our perspectives of these identities and their intersections to engage with the world’s knowledge systems and theories.

Under these circumstances, the rhetoric of who speaks on behalf of whom enters the discourse. Just like how interchanging the subject with the object or vice versa in a sentence makes it sound in a different connotation, the position of the speaker defines the whole theory.

At this juncture, the question “Can the subaltern speak?” and the counter-question “Can dominant society allow the subaltern to speak?” also becomes prominent. Also on the second note, the position related to the community cannot be dynamic but sometimes it may not be as influential as needed. But with the help of virtue of the position what has been done to the community is worthy of consideration and constructive criticism as well. The criticism should be formulated in a way that vouches for the lost voices in the community rather it should not endorse cancel culture.

Ambedkar and his views and efforts towards women’s rights

On this Dalit History Month premise, let us glance at Ambedkar’s disposition towards women’s liberation. One may question, what Ambedkar has to do with women’s progress. Isn’t he a caste leader? What defines his position to talk about women’s issues? His scholarship defines his position to talk on various topics without reducing the complexity of any issue to a simple binary.

With his scholarship, he propounded that endogamy is the reason why caste has been perpetuated in Indian society. He thought that with women’s liberation there lies in the society’s liberation from the shackles of the caste system. He examined ‘Sanatan‘ rituals and customs and theorised that to protect caste, henceforth religious sanctions over the freedom of women have been placed.

In his efforts towards enfranchising women, he has left no stone unturned and it can be reflected in one of the quotes of Maya Angelou that says, “The truth is no one of us can be free until everybody is free.” The intertwined nature of caste and Brahminical patriarchy is pretty much a unique feature that is entirely limited to the Indian subcontinent.

Today’s mainstream Indian feminist discourse fails to acknowledge intersectionality in inspecting the issues faced by people of different social backgrounds of the same group/gender. It has become oblivious to the notions of inclusion and sisterhood.

In her work on Intersectionality: Essential Writings, Crenshaw argues that traditional methods of examining inequality and discrimination are insufficient because they concentrate on specific axes of oppression, like gender or race, rather than considering the interaction of various identities and experiences. Intersectionality is a lens that allows one to observe the points at which power arrives and collides. Today’s mainstream Indian feminist discourse fails to acknowledge intersectionality in inspecting the issues faced by people of different social backgrounds of the same group/gender. It has become oblivious to the notions of inclusion and sisterhood.

Many contemporary women leaders of Ambedkar’s time could not think along the same lines as him on women’s emancipation. It can also be understood as the virtue of his position as a cis-hetero-male he had during that period, but at the same time, we should also remember that he was the only one who fought vehemently for the implementation of the Hindu Code Bill which is intended to codify the different property rules and processes that apply to both men and women by changing the succession order and create new laws for the minorities, marriage, divorce and adoption.

Dr Ambedkar deserves credit for his defence of the Hindu Code Bill and his rationale for resigning from the cabinet in the history of democratic campaigns for women’s rights against the state’s social and patriarchal hierarchy. His work on the caste system did not derive from any renowned theory of any established social scientist. In lieu, his theory was derived from his own life experiences and encounters with caste in society. The theory of experience cannot be found on faulty lines because, in Ambedkar’s case, it was not a mere record of nostalgic events but a theory of anguish that was developed due to abhorrent and vile endurances. Hence, with no further contention, we can say that his expertise has made him one of the most relevant champions of women’s rights even to this day.

Very recently, in the wake of the alleged assault and gangrape of a Spanish woman traveller in the state of Jharkhand, we have seen the pathetic statement coming from the Chief of the National Commission of Women about “defaming the nation” is not a good choice instead of filing a case against perpetrators as a reply to an American-based writer and journalist David Joseph Volodzko who wrote on X formerly known as Twitter about the incidents that account to an abnormal level of sexual aggression he witnessed when he was living in India.

When Ambedkar’s position could be questioned for his statement, “I measure the progress of a community by the degree of progress which women have achieved,” then comes the position of chairman per se which has become futile and stagnant with her stance of national integrity rather than listening to the voices of survivors. Her statement has drawn outrage from netizens across the internet.

Also, it adds that she has turned out to be the gatekeeper of patriarchy hinting towards moral policing and vilification of survivor’s modesty for not filing an official complaint against the perpetrators. Unfortunately, her attitude unveils her ultimate desire to wield power instead of listening to other women. It is, in these instances, said that empathy works more saliently than the position itself.

What is the way forward?

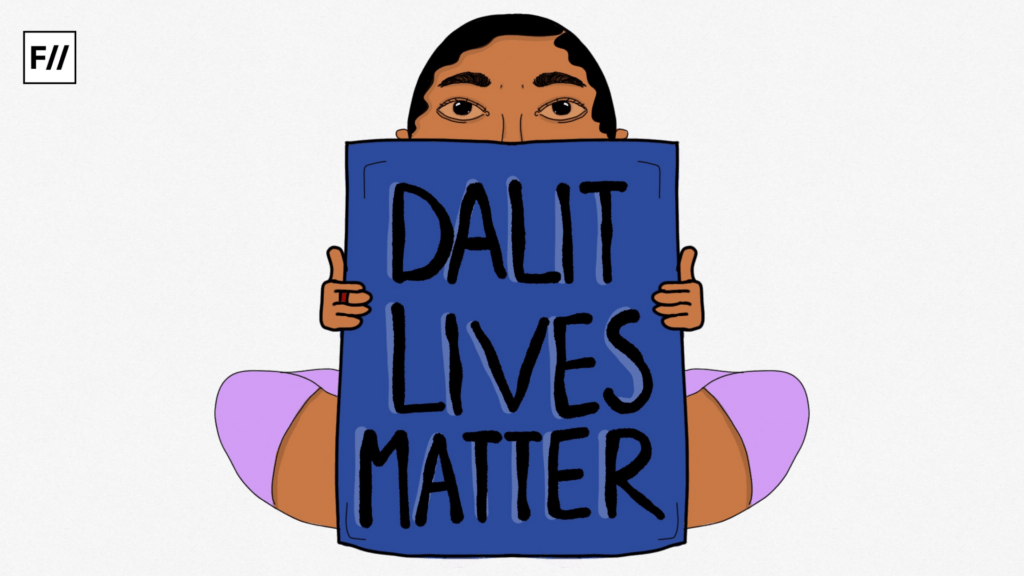

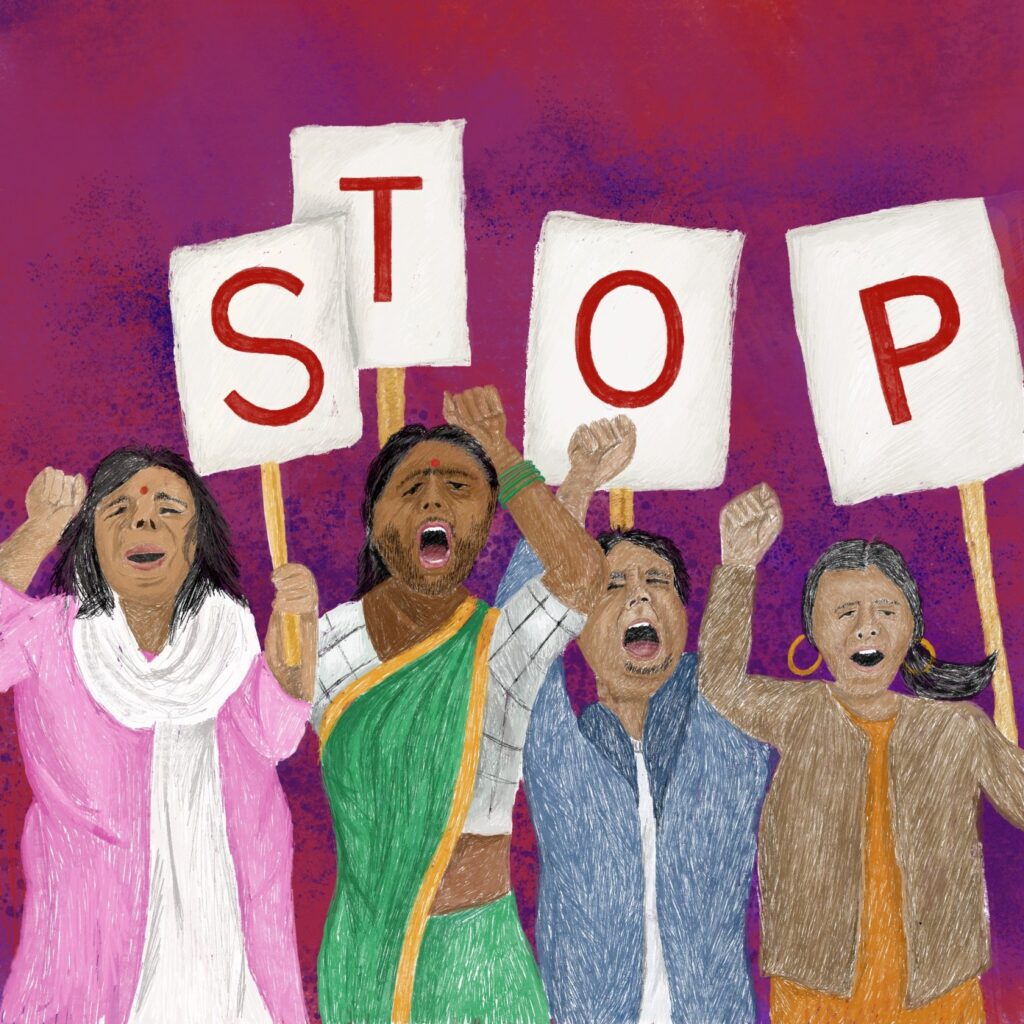

It is not an exaggeration if one might even presume that India is not just struggling with rape culture but gang rape culture. But when Human Rights activists, celebrities and commoners voice out their safety concerns, a horde of bullies starts personal abuse, especially in online spaces from the vantage point of moral policing. When the survivors voice out their safety concerns, they do it out of sheer anger; anger that arises from the helplessness of perpetual reliance on the institutions like family, marriage and government for their security. But their anger is misconstrued to be arrogance at most times.

So, rather than moral policing the survivors or those voicing out their concerns, demanding stringent laws for the capture and punishment of perpetrators will bring the change that all women have been waiting for in terms of safety measures.

The lawful safety measures that are being discussed here are not just limited to the survivors who report the crime but also should be extended to the several unnoticed/unreported sexual harassment cases that have been wrapped under the carpet for the (un)beknowst factors. It is observed in most cases, that this method of gaslighting and moral policing shun women from reporting the crime to the authorities as it brings shame to the modesty of the survivor.

The history of the Indian subcontinent has records of humiliating humans based on professions, castes, genders and sexualities. The propagation of this humiliation stems from the stigmatised religious sanctification for the sake of preserving the hegemony of unified culture and tradition. This violence (both physical and mental) against women by imposing age-old cultural and traditional practices should be seen as not only gender-specific but on a large canvass of human rights challenge.

By examining this pattern of subjugation, it can be said that the real solution to this challenge lies in social emancipation and cultivating a shared sisterhood among women. It is also vital to destigmatise and unlearn many notions that have been perpetuated in our minds for many generations. Resistance against these stigmas and constant (un)learning will be of great use in making safe spaces for women especially those who are from Dalit, Bahujan, Adivasi and Minority communities.

However, the question of safe spaces persists as good and bad notions pertain to ambiguity; the ambiguity of supporting a good notion of women’s rights and empowerment on every Women’s Day and a bad notion of celebrating the immolation of another woman figure. Furthermore, this ambiguity turns antithetical to the whole rhetoric of women’s rights and paves the path for becoming a paradox.

In toto, this paradox is rooted in hypocrisy as the observance of both Women’s Day and the Hindu festival Holi, which is celebrated on the account of the legend “Holika Dahan” (immolation of Holika, a demon woman as per mythology) are marked in our calendars around the same period. In this scenario, can the resistance and anger emphasised above sustain further in this paradox? Deconstruction of these questions gives the way forward.

References:

- Ambedkar, B. R. Waiting for a Visa. Samyak Prakashan, 2023.

- Ambedkar, B. R. Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development. Hilltop Publications, 2021.

- “Angelou: ’no One of Us Can Be Free until Everybody I…” YouTube, YouTube, 29 Aug. 2013, www.youtube.com/watch?v=UxkTd6BFL1o.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. On Intersectionality Essential Writings. New Press, 2022.

- Mukherjee, Arun. “A Note by the Translator.” Joothan: A Dalit’s Life, Samya, Kolkata, West Bengal, 2021.

- Salim, Mariya. “Online Trolling of Indian Women Is Only an Extension of the Everyday Harassment They Face.” The Wire: The Wire News India, 2018, thewire.in/women/online-trolling-of-indian-women-is-only-an-extension-of-the-everyday-harassment-they-face.

- Sarkar, Soumashree. “Amidst Outrage Against Tourist’s Gang-Rape, NCW Head’s ‘Defaming Country’ Response Triggers More Anger.” The Wire: The Wire News India, 4 Mar. 2024, thewire.in/women/spanish-tourist-jharkhand-gang-rape-ncw-rekha-sharma.

- Sharma, Devika. “Indian Women’s Rights Mattered to Ambedkar. Here’s What He Enabled.” TheQuint, 14 Apr. 2021, www.thequint.com/opinion/ambedkar-feminism-women-empowerment-indian-women-right-to-vote-divorce-property-rights-gender-equality.

- TOI-Online / Mar 7, 2023. “Why Do We Celebrate Holi? – Times of India.” The Times of India, TOI, 2023, timesofindia.indiatimes.com/religion/festivals/why-do-we-celebrate-holi/articleshow/98406497.cms.

- Yadav, Asmita. “COPARCENARY RIGHTS AND GENDER JUSTICE: A READING OF DR. AMBEDKAR’S HINDU CODE BILL.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 78, 2017, pp. 1165–71. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26906195. Accessed 1 Apr. 2024.

About the author(s)

PMK Rana is a resident of Hyderabad currently pursuing research in English literature at the University of Delhi. Research interests include Dalit Diasporic studies and Film Studies.