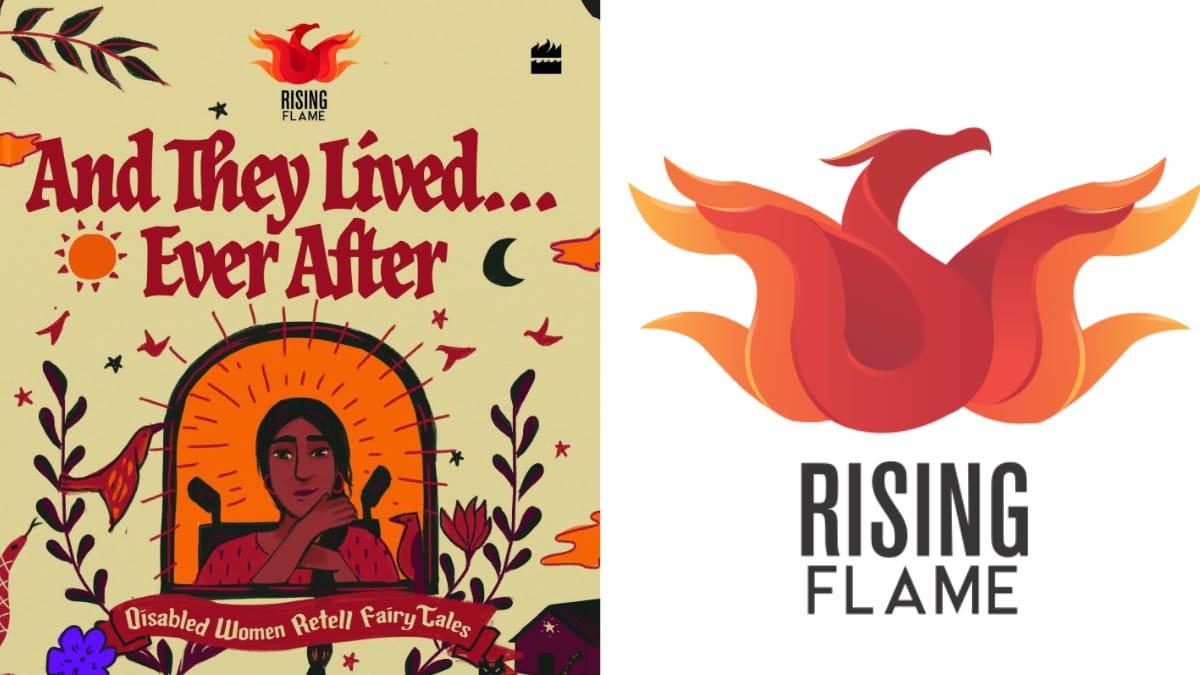

To call the stories in And They Lived… Ever After mere fairy tale retellings would be a gross disservice. Rising Flame, an Indian non-profit organisation working for the recognition, protection and promotion of human rights of people with disabilities, particularly women and youth with disabilities, had anthologised the reimagined fairy tales written by people with disabilities in the collection And They Lived… Ever After in 2020, during a five-month fiction writing workshop and feedback process with author and poet Aditi Rao. Published by HarperCollins, the anthology of thirteen stories by writers with disabilities from across India and Sri Lanka is not just a collection of retellings of age-old fairy tales from the perspective of disability, but rather, a reclamation of popular well-loved narratives to make them reflect the lived realities of women with disabilities.

To call the stories in And They Lived… Ever After mere fairy tale retellings would be a gross disservice.

Growing up as young girls, almost all of us have been exposed culturally to fairy tales like Cinderella, Snow White, The Ugly Duckling etc. But not all of us have seen ourselves represented in these magical stories. The beautiful princesses of these fairy tales were always able-bodied and they had set high societal beauty standards for generations of women to strive towards. Moreover, almost always, these princesses lived “happily” ever after- no matter what their predicament, be it a wicked stepmother or a poisoned apple, there was nothing a kiss from a handsome prince couldn’t cure.

As the gorgeous princess would ride off gleefully with the prince, into the sunset, a demographic of young women consumers of fairy tales would try, in vain, to seek themselves out in the stories that had been fed to them by an ableist and patriarchal society. In most archaic literary narratives, the disabled character is the loathsome villain who terrorises the protagonists or the pitiful waif who is cruelly treated by society and almost always dies in the end so that the protagonist lives. Very rarely, do we see narratives that are disability affirming and celebrate protagonists with disabilities.

In this juncture, it becomes imperative to reclaim the genre of fairy tales and retell these stories through feminist and disability-affirming narratives. In And They Lived… Ever After, the uniqueness of the “ugly” duckling is celebrated, a wheelchair-using Rapunzel is welcomed into the city of Companara, a deaf Snow White regains self confidence and makes new friends and a mother with an amputated leg adds a feminist spin to the story of Cinderella’s so-called “evil” step sister for her young daughter among other narratives which affirm and reflect the lives of women with disabilities.

Different voices, different lives, different stories

Perhaps the best thing about And They Lived… Ever After is the polyphony in the anthology. Multiple voices add their own uniqueness to each story, reimagining the narratives to represent diverse forms of disabilities. In the first story of the anthology, “The Ugly Duckling” by Priyangee Guha, Rakhi/Kaali, the “ugly” duckling is different from the rest of the flock not only with respect to her physical appearance but also her behavioural patterns and her reactions to certain things around her.

Perhaps the best thing about And They Lived… Ever After is the polyphony in the anthology.

The author, in this story, focuses on the developmental disability that the duckling lives with which not only impacts her outward appearance but also the way she copes with the world around her. Rakhi/Kaali is triggered by strong smells and loud noises and finds comfort in repetition, for which she is bullied relentlessly by her peers, until she meets Rekha, who includes her in their flock of swans. The narrative validates the lives of children with autism and mirrors their experiences of navigating the world.

In “Rapunzel and the People of Companara” by Soumita Basu, Rapunzel stresses the importance of independence and self-reliance for people using wheelchairs when she refuses to be carried to the palace by Prince Haloux. Instead she advocates for infrastructural change and only visits the palace when the city of Companara is made accessible and disability-friendly. In this process, she also facilitates social acceptance and inclusion for her caregiver and guardian Mama Lovington, who was previously shunned as a witch by the people of Companara.

From locomotor disabilities, auditory and visual disabilities to developmental disabilities like autism and amputation, the stories in And They Lived… Ever After are testament to the diversity within disability communities and uplift the voices of women writers with disabilities from all walks of life.

From fantastical settings to contemporary situations

The stories in And They Lived… Ever After are not only diverse in their characterisation and the representation of people with disabilities, but also varied in the contextual worlds they inhabit. From anthropomorphic ducks societies with their own schools and other social institutions and fairytale kingdoms like Companara, Veera Puram and other similar mediaeval, almost magical settings, to contemporary societies that are all too real and relatable, the different stories in the anthology are either retold in their original cultural and socio-temporal context or are adapted to contemporary settings in the modern world.

Do we always need a “happily” ever after?: the significance of the endings in And They Lived… Ever After

Most stories in And They Lived… Ever After end on a happy note, or at least a hopeful one, with the protagonist setting out to confront the cruelty of the world with firm resolution. However, Nidhi Ashok Goyal’s modern day Cinderella story “It’s Still Your Choice” ends with the bittersweet pangs of heartbreak and Somrita Urni Ganguly’s “Cinderella’s Sister” ends with a forlorn ‘what if?’

Retelling the age-old story of Ella and her step family to her little daughter, a mother with an amputated leg hesitates on the happy ending, providing a certain ambiguity to Cinderella’s final fate. In the mother’s story, Cinderella’s “wicked” brown step sister is a victim to her cruel mother’s expectations. The story ends leaving readers wondering how it would have been had there been some feminist solidarity between Cinderella and her sister, who had been pitted against each other by the patriarchy.

In the mother’s story, Cinderella’s “wicked” brown step sister is a victim to her cruel mother’s expectations.

The most unsettling and thereby, thought provoking story in And They Lived… Ever After has to be Sarani’s “Red”, a dark and sinister retelling of Little Red Riding Hood, where Biddy, the eponymous young girl in the crimson hood is deaf and lives in a village just recovering from a gruesome war against the ruthless wolf people.

Growing up in the aftermath of the war, Biddy is advised by her mother and grandmother not to wander off into the dark woods and not to speak to strange men. However, when her childlike innocence and adolescent desires lead Biddy to encounter one of the remaining wolf people, who had been banished beyond the Dark Woods, the past trauma of violence comes back to haunt Biddy and her loved ones. “Red” touches on the issue of sexual violence against children and young women with disabilities, discussing their precarity in a predatory world.

And They Lived… Ever After: disabled women reclaim fairy tales

Rather than calling these stories as retellings of fairy tales, the attempt to rewrite the genre should be considered to be an act of reclamation by women who have, till now, rarely seen themselves being reflected positively in the stories they read. The decision to omit the word “happily” from the popular phrase ‘happily ever after’ that we see at the end of fairy tales, from the title to name the anthology And They Lived… Ever After, is informed with the knowledge that happiness, too, is a social construct that is often not accessible to people who live with mental illness like depression.

The very act of not making happiness a parameter for the relevance of a story on disability, reaffirms the real lives of people with disabilities, which, like the lives of most people, are not coloured by perpetual happiness, frozen in time, that we see in fairy tales. Instead, our lives are interspersed with happiness and sadness, and several other emotions and states of mind. The title of the anthology is a nod to the lived realities of women with disabilities, which cannot be masked with flowery euphemism but are supposed to be raw and relatable.

The stories in And They Lived… Ever After underscore one dominant sentiment throughout, which is vocalised by all the women writers living with disabilities- the need for their lives to be seen in our stories, in all their beautiful, honest and unflinching glory.

About the author(s)

Ananya Ray has completed her Masters in English from Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India. A published poet, intersectional activist and academic author, she has a keen interest in gender, politics and Postcolonialism.