Mild spoiler alert.

In one of the episodes of Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Heeramandi (2024), the inhabitants of Shahi Mahal congregate around the dead body of Lajjo or Lajvanti, taking off her anklets and jewelry, before they say a final goodbye to her. In response to a question posed by Waheeda (played by Sanjeeda Sheikh), ‘Should we prepare to say goodbye?’, Mallikajaan (Manisha Koirala) says, ‘One does not say goodbye to a tawaif, one sets them free.’

A historical critique of Heeramandi is pointless, simply because it is decidedly ahistorical—Bhansali eschews history in favor of big, beautiful, artscapes, to the point where it becomes difficult to distinguish the time period in which it is set.

This is poignant, because only in death are women truly free, and for sex workers, death comes as a sweet, sharp release, the liberation from the hunger and greed of men and patriarchy that have worked hand-in-hand to create them. The statement is brave, but ultimately, disappointing.

The historical background of Bhansali’s Heeramandi

A historical critique of Heeramandi is pointless, simply because it is decidedly ahistorical—Bhansali eschews history in favor of big, beautiful, artscapes, to the point where it becomes difficult to distinguish the time period in which it is set. The streets of the original Heera Mandi (not named after diamonds, but the son of a Prime Minister) are not the wide landscapes shown in Bhansali’s imagination, but cramped inner city streets. Mansions of the level shown in the show, both Shahi Mahal and Khwabgah, would be virtually impossible to find in the heart of Lahore, apart from royal buildings.

The iconic skyline of the Badshahi Mosque, one of the most easily recognisable landmarks, is missing from the overhead shots, replaced with large courtyards dripping in crystals and lights. A large body of water flowing behind the fortress-esque set, may lead viewers to wonder if the Ravi flowed behind it.

Bhansali’s works are reflections of humanity, whereby one can see one’s society on the silver screen. However, when one takes too many creative liberties with the lived experiences of real historical people, the vision is shattered. Heeramandi is opulent, to be sure, but under it, is nothing—the eight-episode series is riddled with plot points that are equal parts frustrating, irrelevant, and to the end, confusing.

The characters in Heeramandi

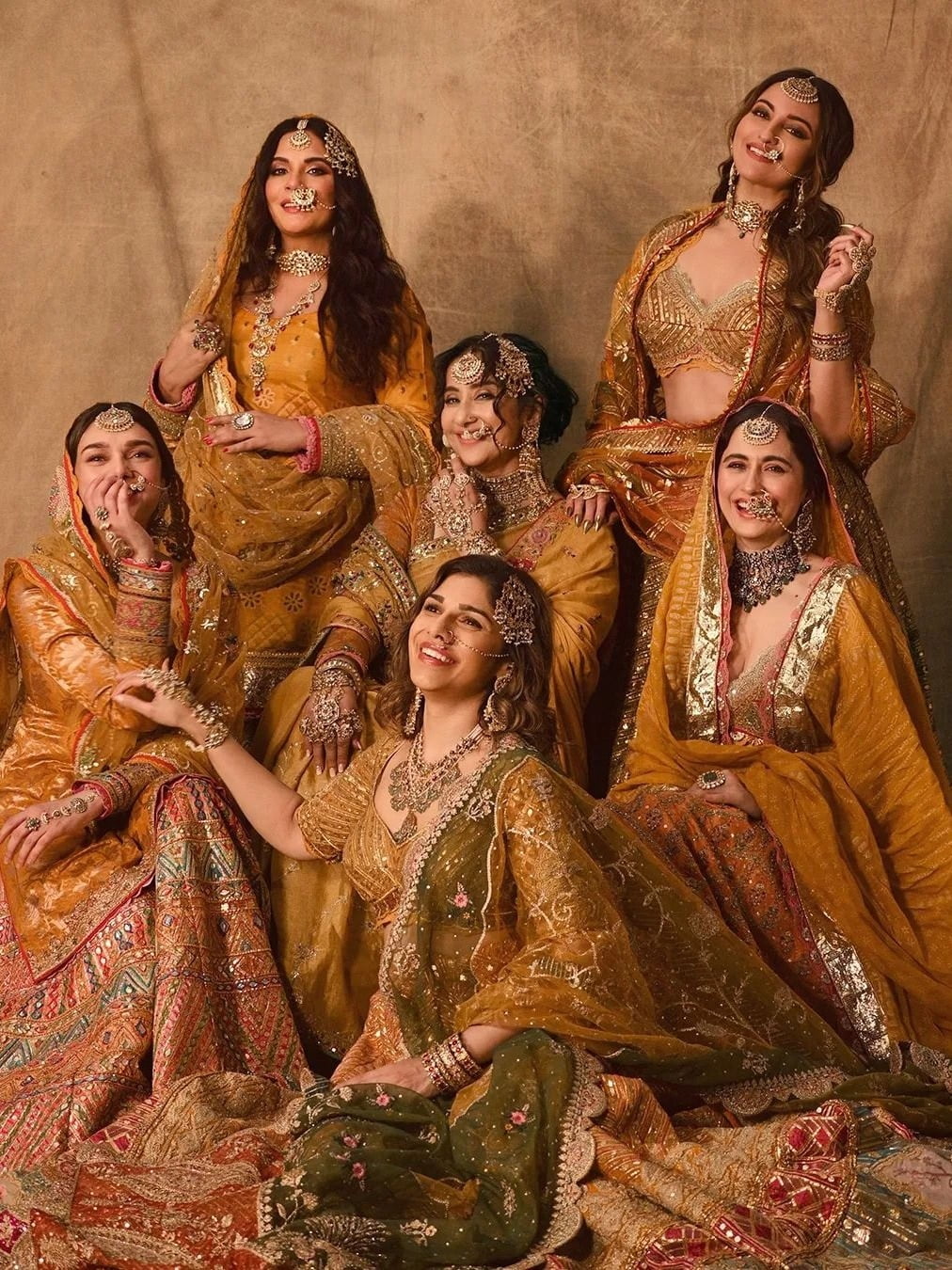

Bhansali is known for his strong characterisation of women, and the well-rounded portrayals of sex workers in his films, as evinced in his 2022 film Gangubai Kathiawadi which landed the primary actress Alia Bhatt the Best Actress Award in both National Film and Filmfare awards. Where Heeramandi falls short is exactly where Gangubai had triumphed; the characters.

Where Heeramandi falls short is exactly where Gangubai had triumphed; the characters.

The screenplay (by Bhansali) and dialogues (by Divya Nidhi and Vibhu Puri) do not do the characters quite right. It all feels uncomfortable, like a masque put upon for the entertainment of the audience. It is ironic that in a show about entertainers, the story feels its own desperate need to entertain, abandoning its duty to be honest with the truth.

A personal favorite performance is that of Jayati Bhatia as Phatto, loyal to Mallikajaan. Phatto has been raised in the Shahi Mahal since she was a child, and while she nurses her own ambitions, she has her loyalty, both a compliment and a detriment to her livelihood.

One of the workers in the Shahi Mahal, she and Nivedita Bhargava (who plays an equally amazing, Satto) represent the hundreds of people who were not the aristocracy or the British, who toiled relentlessly for years supporting a regime that oppressed them brutally. They together represent the old guard of loyal servants, whose dedication to their masters trumps even their self-interests. This, combined with an almost pitch-perfect performance from Shruti Sharma who plays Saima, Alamzeb’s maid, is a delight to see on screen, a welcome respite.

Farida Jalal, as Qudsia Begam is in step with Taha Shah Badussha (who plays Tajdar Baloch) and Ujjwal Chopra (Ashfaq Baloch), the three of them, bringing life to the characters who in the hands of less qualified actors would have fallen flat. The tension between Ashfaq and his son Tajdar, representative of the Old and the New, is acted out quite well onscreen. Badussha is wonderful to see on screen, his expressions finding the tune of an aristocrat, who returns home to discover himself. His scenes with Farida Jalal suffuse the script with some much-needed warmth.

Aditi Rao Hydari as Bibbojaan tries her best, but Manisha Koirala and Sonakshi Sinha manage to capture the attention and refuse to let go.

Lajjo, played by a sparkling Richa Chadha, is one of the brightest moments of the show. Her yearning for romance in a society that does not value her renders her an object of pity and envy. Lajjo manages to free herself before anyone else, as the final gesture of love for Zoravar, she chooses to die by suicide, freeing herself and him in one go. Aditi Rao Hydari as Bibbojaan tries her best, but Manisha Koirala and Sonakshi Sinha manage to capture the attention and refuse to let go.

Koirala’s Mallikajaan is temperamental and vindictive; she gets high on opium and insults a police officer before tucking roses into her blouse in preparation for a poetry-reading session. Likewise, Sonakshi Sinha holds her own. Fareedan is equally as calculating as Mallika- her mind so set on revenge, she disregards the broken hearts left in her wake.

Unfortunately, the towering screen presences of Manisha Koirala and Sonakshi Sinha do not manage to redeem the script. Mallikajaan is ruthless; she conspires to sell Saima for ten thousand rupees for the unforgivable offense of overshadowing her daughter, Alamzeb. She hears her sing two times and decides that the presence of Saima is too dangerous for Alam, and therefore a threat should be eliminated. Mallikajaan’s ruthlessness is made more apparent by her murder of her elder sister Rehana, and her mutilation of Waheeda (yes, it was Zulfikar, but she had no qualms about it).

However, her interests beyond that of herself are murky at best, and unexplored at worst. Mallika forces Bibbo to retire simply to score a win against Fareedan, but was it essential? The rivalry between Manisha Koirala’s Mallikajaan and Sonakshi Sinha’s Fareedan is positioned as one of the primary plot points of the story and is resolved within a matter of mere minutes, without exposing any of Fareedan’s inner turmoil over having exposed her aunt to police brutality. There are far too many plot points in Heeramandi to keep track of, and it seems, even to be resolved.

The tension between Mallikajaan and Alamzeb, reminiscent of the struggle between Ashfaq and Tajdar, is resolved without any character development, and plenty of gratuitous violence.

The tension between Mallikajaan and Alamzeb, reminiscent of the struggle between Ashfaq and Tajdar, is resolved without any character development, and plenty of gratuitous violence. Sharmin Segal as Alamzeb is meant to be the heart and soul of the show; she is a poet and a romantic, who falls in love with an aristocrat-turned-freedom fighter. Unfortunately, Segal does not possess the acting skills necessary to execute such a complicated, dynamic character, and subsequently, her performance is left wanting.

Throughout the show, there is more talk of “sahab”, or patrons, than of the arts. Even a cursory glance across history will tell you that tawaifs were not sex workers, they were highly respected entertainers, who took great pride in their craft. They would have been made to undergo rigorous training in the arts, which they would perform at their mehfils. The Shahi Mahal offers none of the training, and Bhansali implies as though the kothas existed merely for sex work when they were home to rich intellectual discussion, the performers enjoying a high position in the cultural hierarchy.

The tawaif in colonial India

For decades, Bollywood has struggled with the depiction of women on screen, and perhaps the most egregiously in period settings. The culture of purity deeply embedded into the subcontinental mind easily slips into the dichotomy of the Madonna and the Whore when referencing female characterisation. Mainstream Bollywood is not revolutionary, and Heeramandi does not break new ground. Heeramandi suffers from the over-romanticisation of the tawaif culture, reducing it to mere amusement and confirming what had been only a hypothesis; Bollywood’s way of evading the Madonna-Whore complex is found in the tawaif, and nowhere more apparent than in the works of Bhansali.

The tawaif is neither the gentlewoman of period dramas, who would remain virginal in preparation for her marriage nor is she the common “whore”, whose story inevitably deals with the gendered violence that has been wrought upon her by patriarchy. Through the tawaif, one can pretend that the story being told is that of a woman with agency, who, by having some semblance of sexual freedom, has been released from the shackles of patriarchy.

The men of the story suffer no better fates. Were there no Hindu Rajas in Lahore who frequented courtesans? Or are such tendencies confined to Muslim temperaments and tastes?

Unfortunately for Bollywood, tawaifs were not emancipated women, they were victims of a system that intended to keep them in limbo, where they were exploited, but respected. The tawaifs were primarily entertainers, not high-class escorts. In late-19th century Calcutta, Gauhar Jaan, daughter of a baiji Malka Jaan, was trained extensively in Hindustani singing and dancing. Yet there is no mention of it in Heeramandi, and Bhansali’s attitude towards an endangered class of women who were fighting to keep their dignity and their craft alive is to reduce them to mere caricatures.

The men of the story suffer no better fates. Were there no Hindu Rajas in Lahore who frequented courtesans? Or are such tendencies confined to Muslim temperaments and tastes? Unfortunately, Bhansali has not written a well-rounded Muslim character in his films (re: Alauddin Khilji in Padmaavat), and his venture into writing a story populated with mostly Muslim characters seems overtly performative. As to who this performance is for, draw your conclusions.

Heeramandi: empty opulence redeemed by some good acting

In the final moments of the series, the women of Heeramandi make a procession toward the walls of a British prison, singing ‘Azaadi’. The song is eerily reminiscent of ‘Hum Dekhenge’, to the point that it might urge the viewer to browse the credits, hoping to see a mention of Faiz Ahmad Faiz, in vain.

Heeramandi is lush, opulent, and a visual treat, however, it fails to evoke true emotion. It remains empty, like a highly ornamental yet mediocre painting.