Trigger Warning: Mentions GBV

From the remote villages of Bihar to the tribal hamlets of Madhya Pradesh, women are raising their voices against systemic barriers and demanding genuine change. In Salarpur, Bihar, they challenge the efficacy of political reservations amidst pressing infrastructure needs. In Chhoti Inti, Uttar Pradesh, they demand justice in the face of violence and discrimination. Meanwhile, in Angarha, Madhya Pradesh, they highlight the failures of literacy programs and digital exclusion. Across these regions, women demand recognition, empowerment, and a fairer future, urging policymakers to listen and act.

Elections are not just a political event; they are a reflection of the aspirations, struggles, and unmet needs of people. Some voices often go unheard amidst the loud rhetoric of election campaigns. The mahila chaupal (a sit-down candid conversation with women) is an attempt to talk to women voters from rural, remote, and media-dark areas about their political opinions, the issues that matter to them, their views on schemes and policies aimed at them, and their expectations from the electoral process.

Salarpur, Bihar: Unbuilt bridge, unkept promises

In 2006, Bihar became the first state to reserve 50 per cent seats in panchayat for women so it was only fitting to start the mahila chaupal series from the state and talk to women in Patna’s Salarpur village, which has a significant Scheduled Caste (SC) population to assess the effectiveness of these policies on women’s representation in electoral politics.

While there was general awareness about the reservation policy, deeper conversations revealed persistent challenges: ‘How can I possibly stand for elections? I am not educated; I never got a chance to study,’ shared an elderly woman. Even today, education remains inaccessible for young girls, as the village’s long-standing request for a bridge has been ignored. Due to this, the girls can attend school only during exams, as crossing the river is risky, boats frequently capsize, and each year, 5-7 people drown.

The need for a bridge was a recurring theme in the discussion. ‘Just recently, an 18-year-old boy drowned because he couldn’t swim. Imagine his mother’s anguish,’ recounted a woman, her voice heavy with emotion and frustration. Despite election promises, the bridge remains unbuilt, exacerbating their daily struggles.

‘We voted because they promised us a bridge, but nothing has been done,’ echoed the gathered locals to Khabar Lahariya’s Kavita Bundelkhandi. The elderly woman added, ‘All nearby villages, even those with smaller populations, have bridges. I believe we don’t have one because we are an SC-majority village.’

Taking matters into their own hands, the villagers saved money and built a temporary bridge, but it was too fragile and eventually collapsed. To manage daily life, they avoid crossing the river unless necessary. Men wade through the water with their pants rolled up and bicycles on their heads to get to work. Women, lifting their sarees, cross the river to reach the main market, often facing judgment.

‘People might think we’re shameless for lifting our sarees in front of men, but we have no choice,’ one woman explained.

The women are weary of political parties’ empty promises. Most residents have never seen or met their political representative, believing elections are for the rich and powerful given the overwhelming influence of money in politics.

‘If the government truly wants reservation policies to be effective and encourage women like us to run for office, they need to financially support women’s election campaigns,’ suggested one woman, underscoring the need for systemic support beyond mere reservations.

The chaupal in Salarpur, Bihar, brought to light the complex interplay of caste, poverty, and gender in Indian politics. While reservations are a step towards inclusivity, without addressing the systemic barriers of financial constraints and lack of education, they remain a political tool rather than a catalyst for real change. The women of Salarpur don’t want empty promises, but actionable steps to build the bridge – both literal and metaphorical – towards a better future.

Chhoti Inti: Voices against violence and discrimination

Chhoti Inti is a small village with just 60 households, mostly belonging to the Scheduled Caste (SC) community, located in Ayodhya district and about 135 km away from the parliamentary constituency of Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, Gorakhpur. Here, women speak out against violence and discrimination.

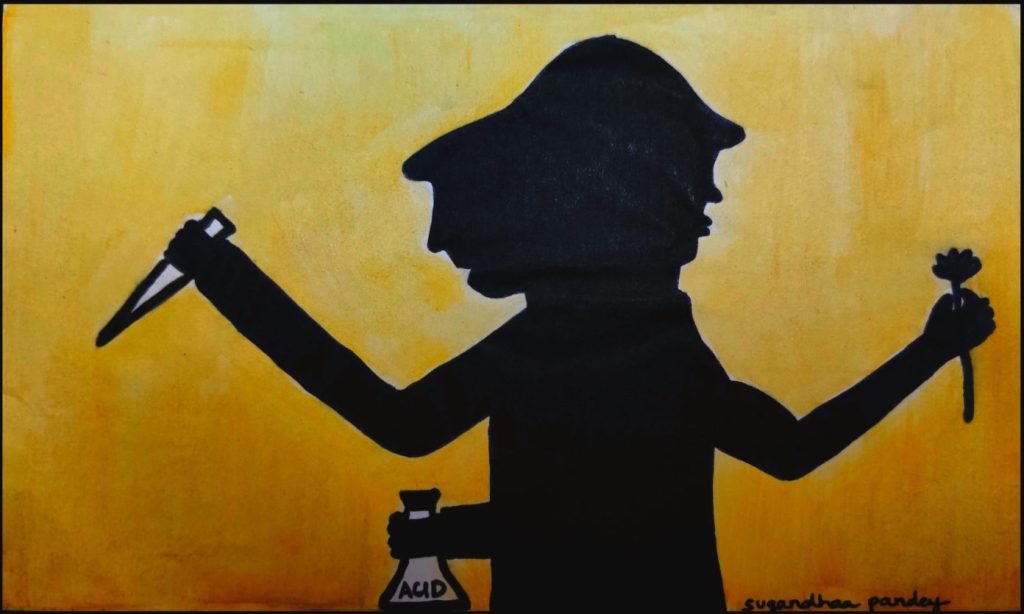

On the night of July 10 last year, at around 2:30 AM, a horrific acid attack forever changed the life of a young girl from this village. As she slept, an intruder entered her home and poured acid on her, leaving her with severe burns and lifelong scars. The police responded quickly, but the physical and emotional trauma remains. ‘I screamed, waking up my mother first, then my brother. They chased him but couldn’t catch him,’ she recalls. Three surgeries later, the pain lingers. ‘Sometimes I feel it would have been better if I had died.’

She has no father, and her brother and mother work hard to cover the costs of her treatment. Despite government promises of support, she has received nothing. Financial aid for acid attack survivors is crucial as their recovery requires ongoing medical care. ‘The government claims that incidents of violence against women have decreased, but it’s all lies,’ she says. ‘I was attacked in the middle of the night in my own home.’

An older woman adds ‘We understand the politics of all political parties. Some claim to work for the SC community and seek our votes, only to use us to gain political power and then forget about us. There has been so much talk about Lord Ram in the last few years, but where is God? Was he here when this young girl was attacked?‘

The women talk about incidents of rapes, acid attacks and dowry-related deaths they hear about frequently, with little improvement in the last ten years. For them, what’s even more disheartening is the lack of economic opportunities for young women. ‘Girls work so hard to complete their education and prepare for competitive exams but it’s so difficult to get a job,’ they say.

Caste-based discrimination adds to their challenges, especially in higher education, where most senior professors and department heads are upper-caste. ‘The rules were different for upper-caste and SC students. It affects everything, from grades to attendance policies,’ one woman explains.

Women also highlight persistent patriarchal attitudes that restrict their freedom and access to justice and economic opportunities. ‘There are still restrictions and judgments on travelling alone, returning late from work, and wearing clothes of our choice,’ they say.

‘Incidents of violence against women, especially Dalit and Muslim women, are almost a daily occurrence, and action is taken in barely one out of ten cases,’ a young woman elaborates. She emphasises the importance of choosing the right political representatives but acknowledges that women here have limited awareness of their voting rights. ‘Votes are often decided by the male members of the family, and women follow their lead. Political parties and local administrations aren’t helping change this reality. Before elections, officials might encourage people to get their voter ID cards and explain how to use the EVM, but that’s not enough,’ she adds.

Kavita asks the group, ‘What can change this reality?’ They believe that having more women in political offices, with real political power rather than nominal representation, is crucial. “We need more women in positions of authority,’ states one woman.

As the Lok Sabha elections enter their final phase, all the women of Chhoti Inti want is to be heard. ‘We deserve to live without fear and oppression,’ they declare.

Women in Angarha, Madhya Pradesh: Uninformed and disconnected

In Angarha, a tribal village nestled in Madhya Pradesh’s Tikamgarh district, the struggle for education among women mirrors a broader challenge in rural India. With a district literacy rate of 61.43 per cent, significantly below the state average of 69.3 per cent, and a glaring gender gap where women’s literacy stands at 49.7 per cent, the uphill battle for education becomes starkly evident.

When we spoke to the women here, they were unsure about any government education or digital literacy programs for them. However, they recalled that officials from the local administration occasionally visit the primary school with documents and forms.

‘Recently, I signed a form that seemed like a blank paper,’ one woman said. ‘I asked the lady there what it was for, and she said Rs. 3000 would be transferred to my account each month, so I signed it. But I haven’t received anything yet.’ She might have been referring to Madhya Pradesh’s Ladli Behna Yojana.

Kavita was surprised that many women signed these forms without fully understanding them. ‘That’s the biggest risk. When women are not educated, they become vulnerable targets. Even if these were legitimate government officials, the real issue is that none of them knew what they were signing.’

The women often seek help from educated people to fill out bank forms and withdraw money. Kavita asked, ‘Are you okay trusting a stranger with your bank account information? What if something goes wrong?‘ One of them replied, ‘I can’t even sign; I use my thumb impression. So yes, I have no choice but to trust strangers, and if something goes wrong, it’s just my bad luck.’

While the country is rapidly digitising, women in Angarha, like many other villages, remain largely disconnected. All the women we spoke to had smartphones, but their use is limited, mostly operated by their children. They use the phones for basic functions like receiving calls. However, due to low literacy, they can’t read or type messages, and a lack of digital literacy skills means features such as voice commands are unheard of and hence, unused.

Reporting by: Team Khabar Lahariya

Written by: Sejal Patel is an independent journalist hailing from Sirali, Madhya Pradesh. They are currently a writer at Khabar Lahariya.