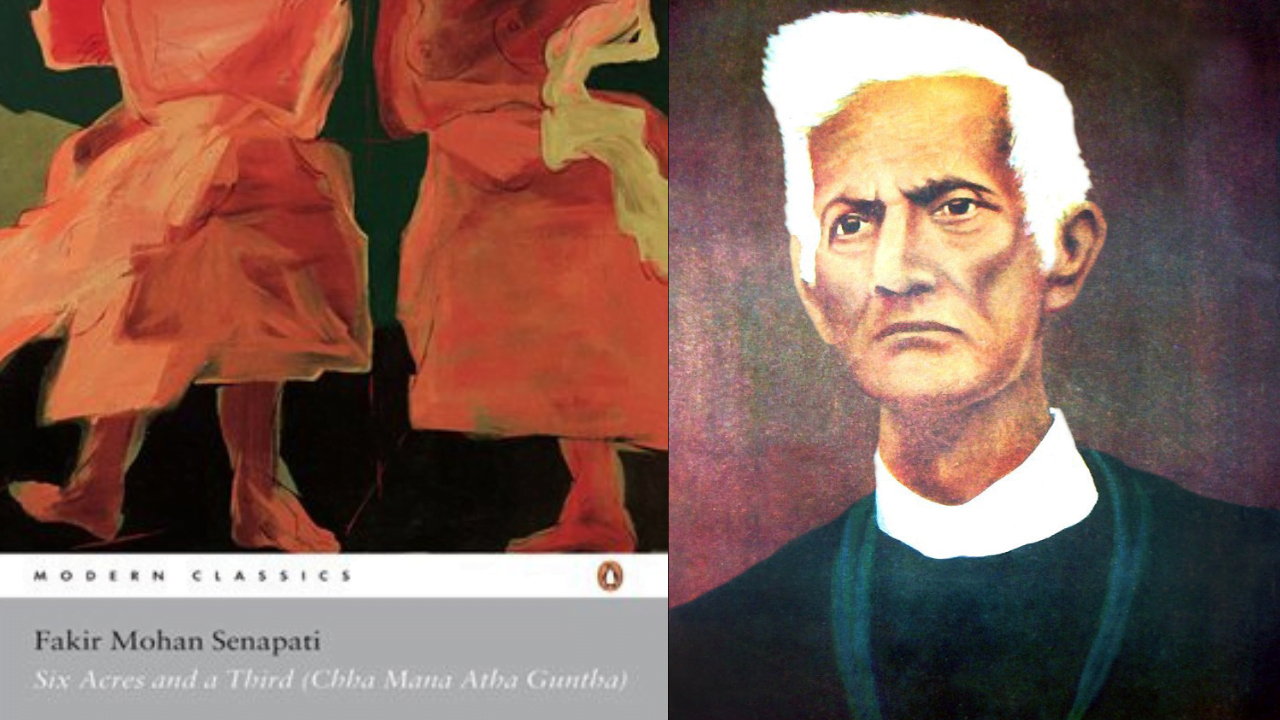

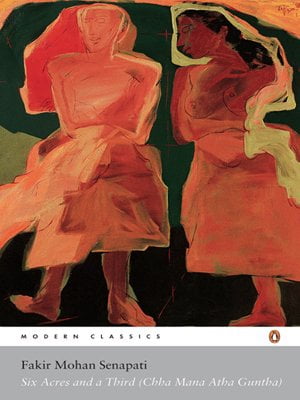

Fakir Mohan Senapati’s Chha Mana Atha Guntha translated from Oriya to Six Acres and a Third by Rabi Shankar Mishra, Satya P. Mohanty, Jatindra K. Nayak, and Paul St-Pierre is a 1902 socio-historical novel that takes a bottom-up approach to unveil the colonial Odisha through the existent caste, class, gender and economic hierarchy.

The innovative satire-driven narrative finely served with humour explores how with the colonisers’ shifting hands, from the Brahmins to the British and vice versa, the pain and ordeals of the downtrodden remain intact.

Six Acres and a Third brings together crisp chapters woven with cliffhangers which although initially look like character assassinations but on closer scrutiny, the chapters dissect the hypocrisy of the society at large. Senapati cuts the thread to his grandiose society dissection through Ram Chandra Mangaraj – an extremely rich Zamindar and money-lender, who fed lots of rice gruel to his farmers before he gave them some rice to satiate their hunger after long hours of labour.

Mangaraj being from the highest rung of society also has been picturised as a sadist who could happily impoverish a lowered caste farmer’s field to populate his own but would never dare to touch him; hence artistically flagging the age-old practise of erstwhile untouchability. Through Mangaraj, Senapati butchers the age-old idea of a true Brahmin who works tirelessly for his subjects and reveals how the ongoing Hindu caste system continues to hegemonise the underserved castes.

Women as means of production and reproduction

Senapati’s female characters read well through a Marxist Feminist framework wherein the women are found at the crossroads of- firstly, as the means of production ranging from catering to food to care, and secondly as the bearer of children; hence the reproductive burden or the motherhood penalty.

The novel ties together the typical notions of considering the family as the prime unit within which the women are trapped in an endless cycle of drudgery under the intersecting patriarchal and economic power structures. It is in this, one discriminatory factor feeding onto another- the patriarchal system and capitalism, Saantani, Mangaraj’s wife gets in a whirlwind of the gendered division of labour in the house and re-productive pain.

From Saantani to Champa to Rukuni, Marua, Chemi, Nakaphodi, Teri, Bimali, Suki, Pata, and Kausuli, the female characters constantly thus get labelled as a wife, mistress, or maidservants, thereby losing their own identity as a woman or in the simplest sense, a human being.

It is interesting to reflect upon the fact that even though the novel, Six Acres and a Third, was written in the early 19th century, it seeks to explore women’s liberation in the truest sense; and intends to position women as equals rather than the Other in family, workspace, or in any available space of existence. This means that the novel caters to a nuanced understanding of gender inequality arising not simply out of capitalistic or patriarchal infrastructure of domination but also due to the intersection of class, caste, and occupation.

Saria, for instance, was a poor weaver, Bhagia’s wife. Treated as an outcast owing to their lowered caste, but her gender positioned her in an even more precarious place. She was burdened with the responsibility of bearing a child. However, Saria could not conceive no matter what she tried, and the villagers trivialised her by stating that a barren woman was worse than a dead one. This tragic gender injustice snowballs into her untimely death. She is chased by the ill whims of Mangaraj’s evil plot to snatch the poor couple’s last straw of existence (a small plot of six acres and a third and her beloved cow, Neta) under the garb of building a temple for a Goddess who would, in turn, bless her with a baby. In due course, she not only loses her land but also herself in the process of clearing the debt of age-old gender and caste discrimination.

Exploitation of nature and oppression of women

Through a brief ecofeminist standpoint, the novel draws parallels between the exploitation of nature/animals and the oppression of women and marginalised groups in society. Through engaging animal imageries, Senapati brings to the forefront how the patriarchal and colonial forces extend also in the animal world. Just as the predatory birds ruthlessly drain resources, women characters like Saria and Saantani are preyed upon and stripped of agency by patriarchal figures like Mangaraj and Champa.

Additionally, the nurturing, life-giving cow Neta is seen to represent the feminine life force, contrasted with the masculinised zamindars and moneylenders who see her as a commodity. Thus, mirrors how women’s co-existence with the animals’ reproductive labour is extracted and their bodies objectified in patriarchal societies. The contrasting portrayals of the innocent Saantani as a lamb versus the vicious cat Champa also play into traditional tropes of pure, nurturing femininity versus dangerous female sexuality and cunning. Senapati very strategically puts forth a metaphor for gynaecological oppression, where feminine nature is conquered, controlled, and pillaged, much like women themselves under patriarchy.

Navigating Indigenous and Colonial Patriarchies

Against the backdrop of colonial rule in Odisha (back then Bengal under British Rule) the birds of prey serve not just as innocent symbols of rapacious colonial powers, but specifically of masculinist colonial domination over colonised lands seen as feminine, penetrable territories to be violated. The colonial attacks to be very precise, extended more than just the land; they cannibalised the language as well. To reduce Oriya to a mere dialect of Bengali and then to shift to English as the ultimate language of progress, development, and prosperity, Senapati draws together a fine bouquet of colonial tactics.

For instance, Champa’s character can be read as portraying the double colonisation of women who face oppression from both indigenous patriarchy (landlords, moneylenders) and colonial patriarchy. Her resort to manipulative, predatory behaviour to navigate the intersecting oppressions of gender and class hierarchies exemplifies the postcolonial feminist critique of how colonised women are compelled to internalise the coloniser’s roles and mindsets for survival.

At the same time, characters like the principled Saantani represent anti-colonial feminine identities resisting total subsumption into colonial domination or patriarchal norms. So Senapati dexterously interweaves a postcolonial feminist consciousness critiquing the intersections of colonial, masculinist, and economic dominations that circumscribe the lives of the colonised female subjects in the novel.

A nuanced exploration of intersectional injustice in Six Acres and a Third

Fakir Mohan Senapati’s Six Acres and a Third thus, proves to be a remarkably ahead-of-its-time novel in its nuanced exploration of intersecting systems of oppression based on gender, caste, class, and colonialism through innovative use of satire and animal imagery.

Six Acres and a Third provides an intersectional feminist critique of how women in colonial Odisha faced compounded burdens and injustices from indigenous patriarchal structures as well as colonial patriarchal domination. Senapati deftly illustrates the myriad ways in which women’s labour was extracted and bodies objectified by both local zamindar elites and colonial capitalist forces.

At the same time, his female characters demonstrate varying degrees of accommodation and resistance to these interlocking oppressions. From the principled defiance of Saantani to the cunning survival tactics of Champa, the novel portrays the complex negotiation of feminine identities and agency in the face of systemic discrimination. Ultimately, Six Acres and a Third emerges as an insightful and original feminist classic that transcends its era to provide a haunting portrait of the brutalities and insidious operations of patriarchy, casteism, capitalism, and colonialism on the lives of Indian women.