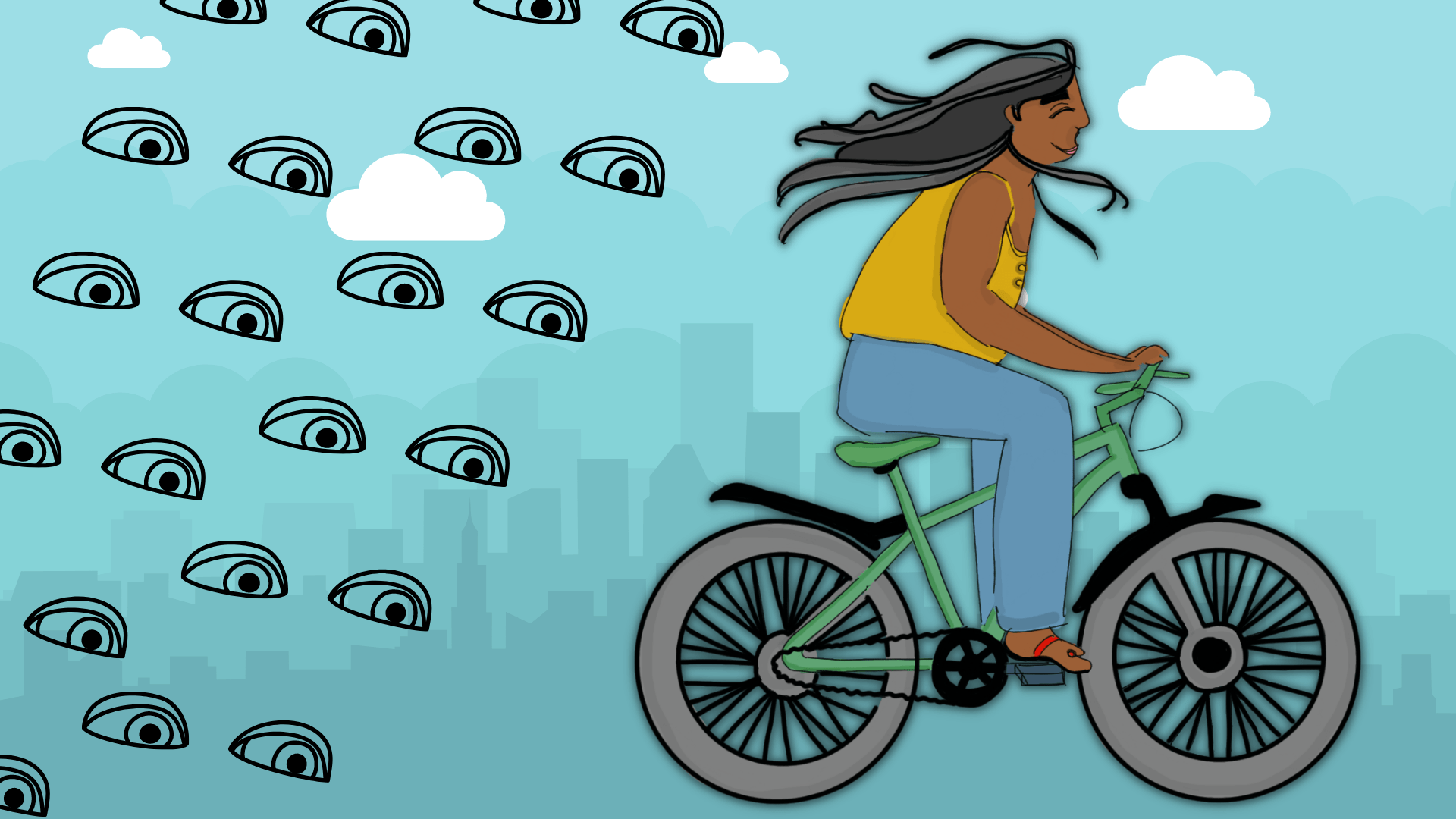

Women have little to no claim over public spaces in the patriarchal imagination. Public spaces (and public life) belong to men – to use or misuse – and women can only encroach upon them at their own peril. Any interactions women have with public spaces are expected to be brief, purposeful, and subjected to a myriad of other restraints.

Any interactions women have with public spaces are expected to be brief, purposeful, and subjected to a myriad of other restraints.

Women have long faced social, economic, and infrastructural barriers when accessing public spaces. But the biggest barrier is crime and the threat of it. While the state has done little to address the crimes against women which deepens the gendered inequality in access to public spaces, the onus of women’s safety continues to be placed squarely upon women.

This reality has once again been brought to the fore after the recent Pune hit-and-run. A seventeen-year-old driver killed two people in Pune on May 19, 2024, while over-speeding and driving under the influence of alcohol. The victims, Ashwini Koshta and Anish Awadhiya, were on a motorbike when the speeding car ran into them. After the perpetrator was let off on bail, widespread public outrage led to the accused being taken back into custody and investigated, alongside several others involved in the case.

But some have been quick to blame the victims, especially the woman who was killed. In a grossly misogynistic display of slut-shaming and victim-blaming, the time of the night when the accident took place, Koshta being out with a man who wasn’t her spouse, and even her clothing at the time of her death was used in attempts to deflect some of the blame onto her and away from the perpetrator.

The fact that questions are being asked of Koshta’s parents instead of the perpetrator’s, who falsified reports, tried to elicit a fake confession, and attempted to impede a police investigation is testament to the patriarchal rot that plagues us.

Some even suggested the parents of the victims (both the victims were adults) should have kept them from going outside at that time of the night and were being negligent by not preventing them from doing so. The fact that questions are being asked of Koshta’s parents instead of the perpetrator’s, who falsified reports, tried to elicit a fake confession, and attempted to impede a police investigation is testament to the patriarchal rot that plagues us.

Why must women justify being in public spaces?

Many responses to such slut-shaming and victim-blaming, in this and many other cases, focus on the fact that there could be a plethora of reasons that made the victim being outside unavoidable. This only goes on to further solidify the belief that women don’t have a right to public spaces. Why should women have to explain or justify their presence in public spaces?

While Koshta is being questioned and blamed for being out that night, the same questions are not being asked of the perpetrator. Men’s access to public spaces is considered legitimate and unquestionable that even when they are misusing these public spaces, their right to be there is still never called into question.

After the 2012 Nirbhaya incident, one of the most commonly asked questions was why the victim was out at night. One of the accused in the case in an interview asserted, ‘A decent girl won’t roam around at 9 o’clock at night. A girl is far more responsible for rape than a boy. Boy and girl are not equal. Housework and housekeeping is for girls, not roaming in discos and bars at night doing wrong things, wearing wrong clothes.’

Women are expected to explain their presence in public spaces to justify being there. They are also expected to have good reasons for being out in public, like work, family emergencies, or other inevitable causes. However, women who occupy public spaces for leisure are viewed with suspicion and contempt and are seen as sharing responsibility for the crimes committed against them. The responsibility to prevent crimes and violence against women in public spaces is shifted onto individual women instead of governments and institutions, just as the accountability for these crimes is shifted onto them and away from the perpetrator.

Social and institutional apathy

The slut-shaming and victim-blaming Ashwini Koshta is being subjected to is symptomatic of a larger problem. These are not merely fringe or individual opinions, they are widespread and normalised beliefs in patriarchal societies that inform and fuel social and institutional apathy towards women who resist or reject the sexist boundaries that limit – sometimes even entirely prohibit – their enjoyment of public spaces.

Shifting accountability onto victims also fosters a culture of victim-blaming and apathy towards female victims within various institutions including policing, courts, and the legislature.

Shifting accountability onto victims also fosters a culture of victim-blaming and apathy towards female victims within various institutions including policing, courts, and the legislature. Often when reporting crimes, women first have to justify being in public spaces and defend how they interact with these spaces.

In the 2019 Hyderabad Disha case, when the victim’s family reached out to the police, the initial police response was to dismiss their concerns. The family was told the victim might have ‘eloped with a boyfriend’ and they were asked if she had ‘lovers or affairs’. Following the 2021 Badaun rape-and-murder case, Chandramukhi Devi of the NCW blamed the victim and said, ‘a woman should keep track of time and should not venture out late.’ In 2022, a Kerala judge dismissed a sexual assault case because the victim was wearing ‘provocative’ clothing at the time of the assault.

There are multifarious instances of institutional apathy. In India, at least one woman files a case against police apathy every two hours. Our institutions continue to fail victims by blaming them for crimes committed against them. This also makes reporting crimes and interacting with courts a harrowing experience for most victims and disincentivises them from seeking legal recourse.

Quotidian violence and the onus of safety

Violence is considered a reality of existing in public spaces for women. But viewing crimes against women as quotidian and an inevitability of women occupying public spaces inspires institutional and social passivity. Women are simply expected to protect themselves in public spaces by withdrawing from them. Because the dominant narrative is that the onus to ensure women’s public safety lies with women, a crucial issue requiring state intervention merely becomes a matter of individual responsibility and personal vigilance.

It is common for families to restrict women’s participation in public life and limit their access to public spaces.

It is common for families to restrict women’s participation in public life and limit their access to public spaces. Such patriarchal control is not only encouraged but is considered integral to responsibly parenting girls. From a young age, women are taught that they must be responsible for their safety by limiting their engagement with public spaces on a need-to basis, accessing these spaces only in the presence of men, and at certain times of the day. Every aspect from if and when women access public spaces to how they interact with these spaces and in whose presence and supervision they occupy it are informed by patriarchal norms.

In Why Loiter?, Shilpa Phadke, Sameera Khan, and Shilpa Ranade explore the idea of women’s right to take risks. They argue that while women should have access to safe public spaces free of harassment, violence, and the prospect of crime, they should also have the right to take risks. This is an important aspect of women accessing public spaces because while we can build safer public spaces, crime cannot be eradicated. Without acknowledging women’s right to take risks, we cannot meaningfully argue for their right to public spaces.

Why Ashwini Koshta was out that night is insignificant. All responsibility for her and Anish Awadhiya’s death exclusively lies with the perpetrator and those who abetted his crime. Women have an equal and unequivocal right to exist in, occupy, and engage with public spaces. Even when they are accessing public spaces solely for leisure. While state interventions like infrastructure that is planned centring women’s needs and their safety, efficient policing and gender diversity in policing, and accessible and affordable public transport are necessary for equalising access to public spaces, these interventions are no good without dismantling patriarchal frameworks that hinder women’s access to public spaces and attempt to delegitimise their claim to it.

About the author(s)