Born to her Devadasi mother Putta Lakshmi in the year 1878 in Nanjangud (located in the present-day Mysuru district of Karnataka), Nagarathnamma went on to become one of the most renowned Carnatic classical singers, activists and scholars of her time. Determined to educate her daughter in the arts of singing and dancing despite her dwindling wealth, Putta Lakshmi left no stone unturned. The result was a brilliant girl who at the mere age of nine had the capability to make her guru and great Sanskrit scholar Giribhatta Thimmayya Shastri insecure with her rapid progress. Her extensive knowledge of Sanskrit, Kannada, Tamil, Telugu and English distinguished her as a woman who achieved exceptional heights.

Though conveniently erased from the mainstream cultural history of India, Nagarathnamma’s life provides a unique account of a Devadasi who relentlessly fought for the cause of women and her community till the end.

Though conveniently erased from the mainstream cultural history of India, Nagarathnamma’s life provides a unique account of a Devadasi who relentlessly fought for the cause of women and her community till the end.

Raga Ratnam (the ‘jewel’ of music): Nagarathamma’s music career

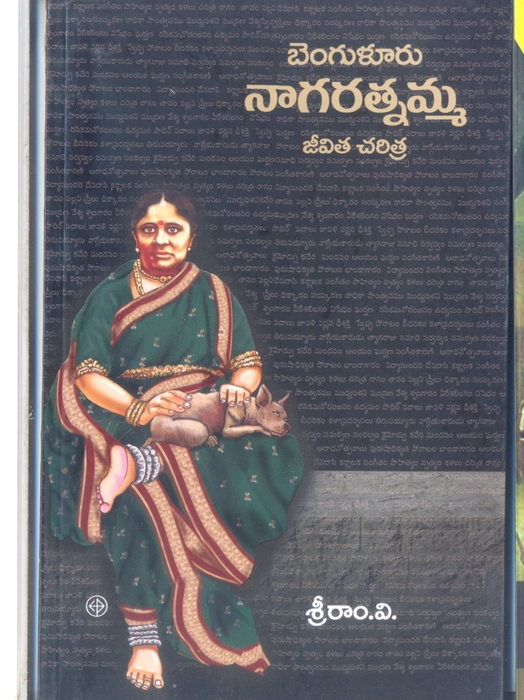

In Nagarathnamma’s biography1, Sriram V. accounts, ‘“In these 26 years, Nagarathnamma has performed in 146 cities,” wrote a source in 1931. “On the whole, 1235 concerts were performed in the Tamil speaking country. In Madras alone, she has performed 849 concerts.”’ Aware of the precarious future of the Devadasi culture due to the repeated persecution by the British colonial government, Nagarathnamma eventually gave up performing dances.

However, as the numbers above indicate, her popularity boomed as a singer. The famous Carnatic musician and composer Mysore Vasudevachar commented that Nagarathnamma’s voice was a unique combination of ‘the melodic sweetness of the female voice and the dignity of a male voice.’ Her training in Bharatnatyam, Vasudevachar notes, contributed to her ability to emote through her singing.

Nagarathnamma’s frequent travels across various cities and towns necessitated the invention of a more compact and portable instrument which she could carry with her during her performances. She designed a dismantlable tambura (the classical music instrument) – an instance that reveals her unconventional and inventive genius.

By 1905, Nagarthnamma’s frequent concerts amassed so much wealth that she began to pay income tax. Her performances provided economic independence and safety, which she cherished due to her exposure to poverty during childhood. Her pride in her numerous jewels and silk sarees is reflected in her bedecked portrait photographs. In a time when few other working-class women in India were adept at managing their finances, Nagarathnamma’s meticulous records stand out as testaments to her financial intelligence.

The rise of the gramophone by the end of the 19th century and early 20th century opened up new possibilities for singers to preserve their music for posterity.

The rise of the gramophone by the end of the 19th century and early 20th century opened up new possibilities for singers to preserve their music for posterity. Hesitantly ignoring the varied myths associated with gramophone within the community of Indian classical singers and battling with the fear of losing her vocal power, Nagarathnamma became one of the earliest singers to feature in gramophone recordings.

As the Anti-Nautch Movement against the Devadasi system gained momentum in the early 1900s, the possibility of the extinction of their profession approached nearer. In a calculated attempt to find other means of employment, Nagarathnamma began performing Upanyasams (religious discourses) for private audiences. Her extensive knowledge of Sanskrit aided her endeavours as a professional orator.

Tyaga Ratnam (the embodiment of sacrifice): restoring Tyagaraja’s samadhi

Nagarathnamma came to recognise the 18th century Carnatic saint Tyagaraja of Tiruvayyaru as her favourite composer. In her concerts, she regularly performed his songs and was often seen carrying his portrait with her wherever she went. It was through a letter from her guru Bidaram Krishnappa that she learnt about the deteriorating and neglected state of Tyagaraja’s samadhi and its surroundings. Unaware of the existence of the samadhi until that day, Nagarathnamma immediately made it her life’s mission to renovate it with her resources.

However, in the eyes of the patriarchal Hindu religious community, her contribution to the restoration of Tyagaraja’s samadhi did not obliterate the fact that she was a woman, and therefore impure by birth. Participation in the Aradhana celebration (a five-day festival held in honour of the saint) was exclusively open to men. Fuelled by her anger upon being denied the right to attend the celebration, Nagarathnamma declared that she would host an Aradhana exclusively for women.

It was in January 1927, that Tiruvayyaru witnessed 40 Devadasi women joining this celebration. Nagarathnamma inaugurated the ceremony with a powerful speech and the event was a huge success. She continued to conduct the Aradhana for the subsequent years, hoping to instil interest in Tyagaraja’s compositions in women. Her efforts led to the transformation of Tiruvayyaru into a cultural and educational centre. The trust found in her name continued to fund Tyagaraja’s samadhi after her death.

Linking Nagarathnamma’s social activism to feminist thinking

When Nagarathnamma came across Radhika Santwanam (Appeasing Radhika) or Ila Deviyamu (The Story of Ila) by the 18th century Telugu Devadasi poet Muddupalani, she found in her poetry an expression of her own subjectivity and creative ideal. Contrary to the tradition of mainstream bhakti poetry where Krishna’s erotic pleasure is central, Susie Tharu and K. Lalita note that in Muddupalani’s Radhika Santwanam, ‘the woman’s sensuality is central. She takes the initiative and it is her satisfaction or pleasure that provides the poetic resolution.’

Nagarathnamma read the original text against the highly censored and reductively edited version published in 1887 by Venkatanarasu, an associate of Orientalist C.P. Brown. She was enraged by his omission of Muddupalani’s prologue where she traces her matrilineal descent and establishes herself as a court poet of Pratapasimha from his edition.

Shocking and scandalising colonial Madras, Nagarathnamma published the full text in 1910 through the Vavilla Ramaswami Sastralu and Sons publication house. The text immediately received harsh criticism and backlash from conservative scholars and government alike. Kandukuri Veeresalingam, who viewed the Devadasi system as a social ill, wrote one of the harshest and most dismissive criticisms of Muddupalani’s work.

Shocking and scandalising colonial Madras, Nagarathnamma published the full text in 1910 through the Vavilla Ramaswami Sastralu and Sons publication house.

Veerasalingam viewed the epic as a work of a ‘prostitute’ — ‘It is bereft of the modesty that one expects of a woman and she has filled the book with graphic descriptions of lovemaking in a very crude manner. Parts of the work are such that they should not be heard or read by women.’ The editorial of the conservative Telugu magazine Sasilekha similarly published its remark on the new edition in January 1911, claiming that ‘a prostitute composed a book under the name of Radhika Santwanam (Radha Reconciled) and that another prostitute corrected errors therein and edited it!’

In her defence of the new edition, Nagarathnamma argued against viewing Muddupalani as an ‘unchaste’ “prostitute” because of her Devadasi status. According to her, social qualifiers used for women such as “chastity” were not applicable to Devadasi women, since they never married men. She also criticised Veerasalingam’s hypocrisy in only being dismissive of the text by Muddupalani, while editing far more graphic sexual descriptions by male authors. In a bold feminist streak, she questioned if shame was solely to be considered the virtue of a woman.

However, all of Nagarathnamma’s attempts to defend her publication were wasted on the government. The book was condemned as ‘morally injurious’ by the colonial government under the provision of section 292 of the Indian Penal Code. In 1911, the Police Commissioner Cunningham seized all copies of the new edition. Nevertheless, the books continued to circulate despite the government imposed ban. It stands as a testament to Nagarathnamma’s unrelenting endeavour to embolden the voice of another Devadasi woman bestowing literary expression to women’s sexual desires.

The Anti-Nautch Movement of the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century in colonial Madras threatened the very existence of the Devadasi community. The proponents of the movement viewed Devadasis as “prostitutes” and attempted to curb the problem of young girls being dedicated to the temple for their entire lives. The erstwhile respect that Devadasis commanded due to their religious affiliation to the temple and their status as performers and artists eventually waned.

Nagarathnamma played a leading role in the protest against this movement. On 20th December 1927, the Devadasis drafted a memorandum pleading for their case and sent it to Sir C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar, the famous lawyer and administrator of the Madras Presidency. Titled The Humble Memorandum of the Devadasis of the Madras Presidency and written in refined English, the draft is believed to have been largely the work of Nagarathnamma. The memorandum attempted to dismantle the equation of Devadasis to “prostitutes”.

Nagarathnamma played a leading role in the protest against this movement. On 20th December 1927, the Devadasis drafted a memorandum pleading for their case and sent it to Sir C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar, the famous lawyer and administrator of the Madras Presidency.

In Nagarathnamma’s biography, Sriram V. succinctly summarises their requests in the memorandum, ‘Demanding that their right to live, which was spelt out in the Sastras [sacred scriptures], ought to be protected, they argued that the proposed legislation would only increase the tendency to prostitution as they would be deprived of their “honourable source of living”. They would become destitute if the Bill was passed, the document said, and claimed that all of them would be thrown into the “very jaws of hunger, despair and prostitution.”’

Nagarathnamma assumed a leading role as the Secretary of the Devadasi Association. The Association believed that the Devadasi community played an important part in preserving the art of singing and dancing, and the abolition of their community would ensure the extinction of these art forms. Fighting for the human rights of the marginalised women of her community irrespective of their eventual defeat, Nagarathnamma sets a historic example of resistance and resilience for social activists.

These accounts from Nagarathnamma’s life carve the portrait of a woman who fearlessly confronted patriarchal institutions. Moving beyond the immediate requirements of her artistic profession, she endeavoured to empower women and expressed immense joy upon coming across talented young female singers. Though most of her possessions were donated to Tyagaraja’s samadhi, she gave away her gold bracelet to the Sarada Niketan, a rehabilitation home for widows.

However, Shaik Mahaboob Basha’s essay on V. Saraswati reveals Nagarathnamma’s dismissal of the possibility of power imbalance and subjugation of women within the domestic sphere. Perhaps her understanding of the nuances of a married woman’s experience of the domestic space was limited due to the independent lifestyle that emboldened her. Her earnest protests against Devadasis being categorised as “prostitutes” similarly operate largely from a need to convincingly plead the cause of the marginalised community of Devadasis to a patriarchal, orthodox society and government, guided by Victorian ideals of ‘feminine’ conduct and behaviour.

Nagarathnamma’s subjectivity was defined by heterogeneous forces. Her ideals congealed against a yearning to preserve the tradition of her community, and at the same time was coloured by her confrontations with oppressive patriarchal institutions that working and religious women were subject to. Her daring steps against the dictates of the patriarchal religious order and scholarly tradition or her lustrous career within the male-dominated world of classical musicians bear testament to her capabilities.

Footnotes

- Incidents from Nagarathnamma’s life are described as found in the 2007 biography of Nagarathnamma by Sriram V., The Devadasi and the Saint: The life and times of Bangalore Nagarathnamma.

Resources–

Gramophone recordings of ragas in the voice of Nagarathnamma, Source: Archive of Indian Music,

Image of the granite plate outside Tyagaraja’s samadhi in Tiruvayyu, recording Nagarathnamma’s contribution to its construction, Source: Google images, https://images.app.goo.gl/mtU68xwTvdHH18bXA

About the author(s)

Madhusmita Mukherjee (she/they) is a queer feminist writer and photographer from Assam who is passionate about advocating gender equality and social justice. She completed her postgraduation in English from the University of Delhi (2022-24). Her academic interest lies in gender studies, media memory and cultural studies. Her recent publication features in the Zubaan anthology Riverside Stories: Writings from Assam edited by Banamallika.