Spoilers ahead!

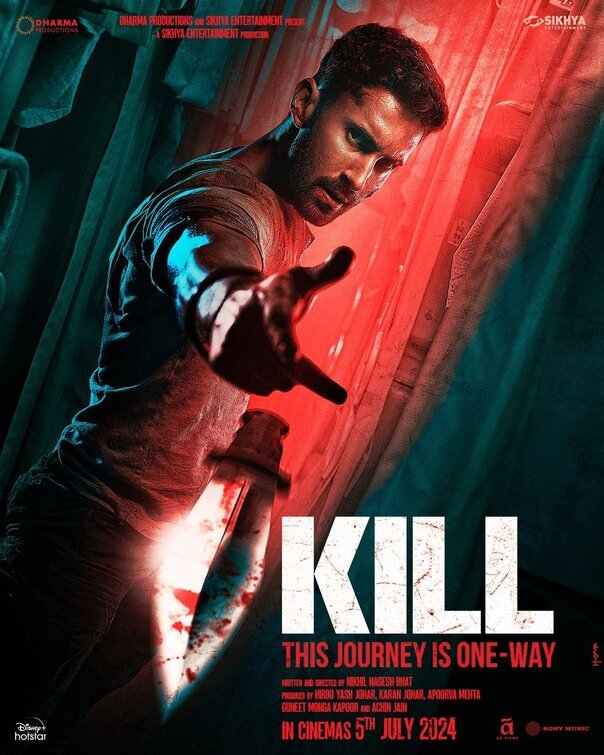

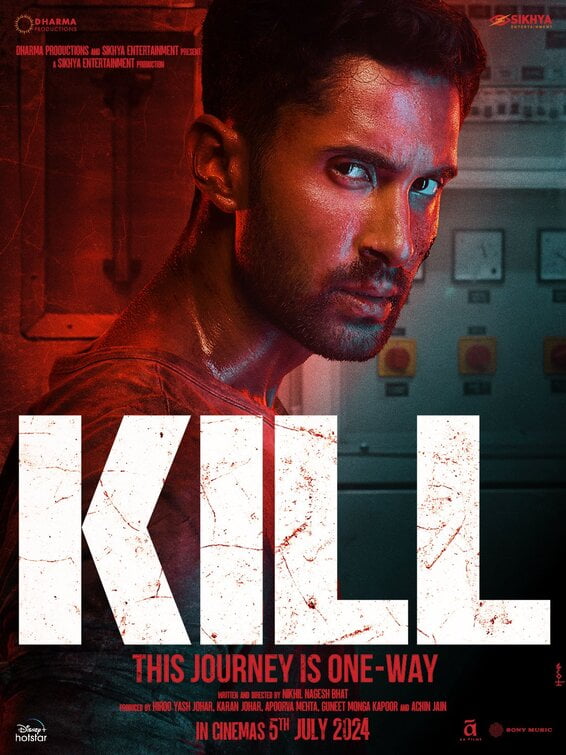

It is the most un-Bollywood-esque film Dharma has produced in recent times (or ever?). Backed by Karan Johar’s Dharma and Guneet Monga’s Sikhya, Kill is undoubtedly the most delicious serving of splatter and gore in Indian cinema’s history. It is no surprise that the splatter-revivalist Lionsgate wishes to remake it in Hollywood. But that holds little relevance to what Kill achieves in the two hours – a splatter fest rooted in shudh desi weapons, politics and emotions. A decidedly dark sky with no stars to draw your attention, Kill presents an evenly formidable cast of actors – led by Lakshya and Raghav Juyal. With a few unremarkable titles under his belt, this is almost a symbolic debut of Nikhil Nagesh Bhatt’s capacity to deliver style and content. A week after dystopic India, it is time to venture into splatter India.

Contextualising Kill: Splatter genre, Asian extreme cinema, and India’s abstinence

In the early 1960s, horror cinema took a sharp turn towards a genre that would soon come to be known as splatter horror – from Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho to Hammer Films’ productions like The Curse of Frankenstein. There are aesthetic roots of this genre in the likes of DW Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) or the French Grand Guignol theatre-gore. Since the beginning of modern splatter horror, Asian Extreme cinema has always had an edge over others – from Nobuo Nakagawa’s Jigoku (1960) to Takashi Mike’s Ichi The Killer (2001) to Kim-Ki-Duk’s Moebius (2013).

Since the beginning of modern splatter horror, Asian Extreme cinema has always had an edge over others – from Nobuo Nakagawa’s Jigoku (1960) to Takashi Mike’s Ichi The Killer (2001) to Kim-Ki-Duk’s Moebius (2013).

While our neighbours have been busy turning humans into chopped livers, India has treaded this genre carefully. A few films from the South might make the mark of a slasher-horror, but almost none has come close to splatter. That is until now. Before we talk about the film – if you can stomach some flesh and blood, please watch Kill, and yes, on the big screens.

For anyone new to the genre, splatter promises a bloody fest of stylised body horror with a lot of flesh and tissues flying about. It treats gore as an art form and special effects – practical or visual – as its dearest tool. Chaos mostly wins over morality. Our very own splatter-esque Kill toes this line of morality, with a relevant political subtext. The film opens quite mellow with the promise of a Bollywood romance but hurries to snuff it out to exchange Bollywood mush for brain mash.

Imagine Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, this time not only are Raj and Simran on the train but their entire khaandaan is travelling. Simran, aka Tulika, played by the doe-eyed Tanya Maniktala gets engaged to the groom of her father’s choice. But that is to hoodwink her parents and secretly marry her Raj, aka Commando Amrit Rathod, played by Lakshya. Tulika’s father Baldev Singh Thakur is the transport minister and for some unknown undisclosed reason is anticipated to disapprove of Amrit (Spoiler alert: “Yeh Raaz Bhi Usi Ke Saath Chala Gaya”).

Imagine Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, this time not only are Raj and Simran on the train but their entire khaandaan is travelling.

Yes, they are in love, yes, we know this cannot end well – but thankfully Bhatt does not worry about creating an elaborate emotional context – any seasoned Indian audience would retrieve the nearest media memory and build the necessary foundation. A few happy memories and moments later, we enter the hallowed hallways of Indian railway coaches. Rings are exchanged, the robbers or dacoits have taken their place and the phone towers have been jammed – and enter the most darling dacoit one has ever laid eyes on – Raghav Juyal’s Fani.

Bhatt’s sincerity towards the story and the form shines in how the band of dacoits has been cast. They are not just body numbers but characters with names and relationships with each other – Badlu, Kulli, Siddhi, Bechan, Mukund – played by actors and not stunt actors. Action, as we know it in Indian cinema, is designed the way we plan our dance sequences. The nondescript extras appear and disappear like objects in a set. Kill defies this tendency and tries its best to establish a human connection between the audience and the bodies.

Ashish Vidyarthi’s ageing, stocky, moralistic dacoit leader Beni is a fantastic foil to the young, lean and loose Fani. The first half is a timid and almost vanilla action film. Despite rescuing us from the romantic exposition, Bhatt takes an inordinate amount of time for the psychosis to set in. Amrit’s friend and colleague Viresh is played very handsomely by Abhishek Chauhan. It is a clumsy and messy first half with both sides – dacoits vs civilians, losing people, one side albeit heavier on the flesh scale. It is a defence against the dacoits through this half.

The two commandos seem beaten to the inch of their lives till the most crucial death occurs. Making way for a grisly and fantastic second half, mostly. A special mention for the title card placement, a rather enjoyable reminder in the middle of the film. Stylistically the film is remarkable, especially knowing that the film majorly uses practical effects and not VFx. The music is racey and adequate, while the track “Kawaa Kawaa” causes significant impact as punches land to the sound of rifles cocking.

A bloody second half: squelching, squishing, oozing

If you are shocked and insulted by the show of violence – it would probably be better if you leave before the second half. Post-interval Kill’s gory acceleration delivers all that the trailer had promised, and then some more. Bhatt keeps Kill rooted to its desi heart through the weapons used in the film. It starts with a kukri – a Nepali short sword, wielded with gusto and craft by Juyal’s Fani. The wooden-handled hammer is the most common weapon in Kill’s creative arsenal. There are daggers and desi kattas – that unequivocally malfunction. There is a surprising use of zippo lighter as well.

Set inside the claustrophobic setting of a railway coach – what else can one use but every part of it? From the pristine white sheets to the fire extinguisher to the emergency hammer kit to the creative use of the underside of the upper berth – there is little of the setting that has not been used as a tool to kill. The fire extinguisher scene calls back memories of Gaspar Noe’s bloody masterpiece – Irreversible. Bhatt does a double nod as he also recreates an almost identical scene from The Midnight Meat Train.

The fire extinguisher scene calls back memories of Gaspar Noe’s bloody masterpiece – Irreversible. Bhatt does a double nod as he also recreates an almost identical scene from The Midnight Meat Train.

As the bodies of dead dacoits, hanging from the ceiling, are met by the live ones – it is one of the most emotional scenes of the film as the bodies are lovingly brought down and mourned by the members. Having lost all bearings Amrit goes on what can only be described as a murderous rampage. Siddhi, played by Parth Tiwari is the most terrifying and nefarious of Amrit’s opponents. His death is not delivered by either of the commandos but by two civilian mothers one of whom lost their child to his knife.

The effect of that scene is immense, not only in the emotional aspect of violence as a form of passionate grief but also in the way he dies. His helpless flailing and the number 24 written with blood on his chest stir something in the story that until now was focused on squelching, squishing and oozing.

Moral questions of Kill: whose side are you on?

Bhatt has expressed his love for James Cameroon’s Aliens in the series of interviews he has given after the film. He talks about wondering how the film would look if it was told from the point of view of the aliens. His inspiration is evident in the way he questions the moral sides of the story. Fani, the mean and slippery young dacoit is not only the unpredictable agent of chaos but also the one posing the most relevant questions throughout the film – pulling the audience to see the carnage from the lens of the dacoits. After losing a few men Beni decides to enter the scene to control the situation but Fani refuses to leave without kidnapping the minister for ransom. He questions his father, Beni, about what he plans to do for the family of the deceased dacoits to ensure they are not left hungry.

This brings back the audience from the adrenaline-induced stupor to the reality of class. In Fani’s opening scene, we see him as a worker at a gas station where he begrudgingly receives a call from his father and heads towards the train, grumbling. It is a very important call back to the context of the characters. Fani laughs at his father’s face who boasts of morality and gives him a harsh reality check of being a robber – but this also creates a larger question about the moral frameworks of the previous generations as opposed to the newer ones.

The power inequality of the two classes – passengers of an AC coach and a gang of bandits – could have been the central theme where the plot jerks you back and forth, forcing one to question the morally rightful side.

Beni at another point refuses to leave the minister behind in fear of his power – he reminds his team that while Thakur might be helpless in the isolation of the coaches, in the real world his power is so immense that none of them would be able to escape. The power inequality of the two classes – passengers of an AC coach and a gang of bandits – could have been the central theme where the plot jerks you back and forth, forcing one to question the morally rightful side. But that is not what Kill ends up becoming.

Near the end of the film, as Fani looks on at a frenzied Amrit demolishing his colleagues, horrified he asks Amrit, ‘Aise kaun marta hain bey?’ He goes on to call him a demon and not a defender. These questions come a little late in the story for the words to truly sink in, but it is a thought one leaves the cinema hall with. Death of forty against four. Where does defensive action turn into blood lust? Amrit does not merely kill the members of the band, he seems to make exquisitely cold decisions to destroy their bodies.

The film and the train draw at the final station – but the ending scene might be the most Bollywood Bhatt gets. With a Ghajini-esque scene the screen goes blank, and one wonders if it would have been more satisfying to see both Fani and Amrit die on the same short sword. Most might still be well even if all does not end that well. Revenge delivered as a meat platter – no complaints.

When splatterpunk literature arrived during the 1970s, amidst outrage and dismissal the genre received praises from defending critics who saw this “survivalist” literature as a reflection of the moral chaos of the times. There have been concerns about a film like Kill at a time when people are busy baying for each other’s blood and have been desensitised by war and crime. While it could have been merely torture porn, Kill emerges above that as it turns body count into characters and questions morality through the bloodbath. It is a film that will be remembered for its craft and heart.

About the author(s)

She/they is an editor and illustrator from the suburbs of Bengal. A student of literature and cinema, Sohini primarily looks at the world through the political lens of gender. They uprooted herself from their hometown to work for a livelihood, but has always returned to her roots for their most honest and intimate expressions. She finds it difficult to locate themself in the heteronormative matrix and self-admittedly continues to hang in limbo