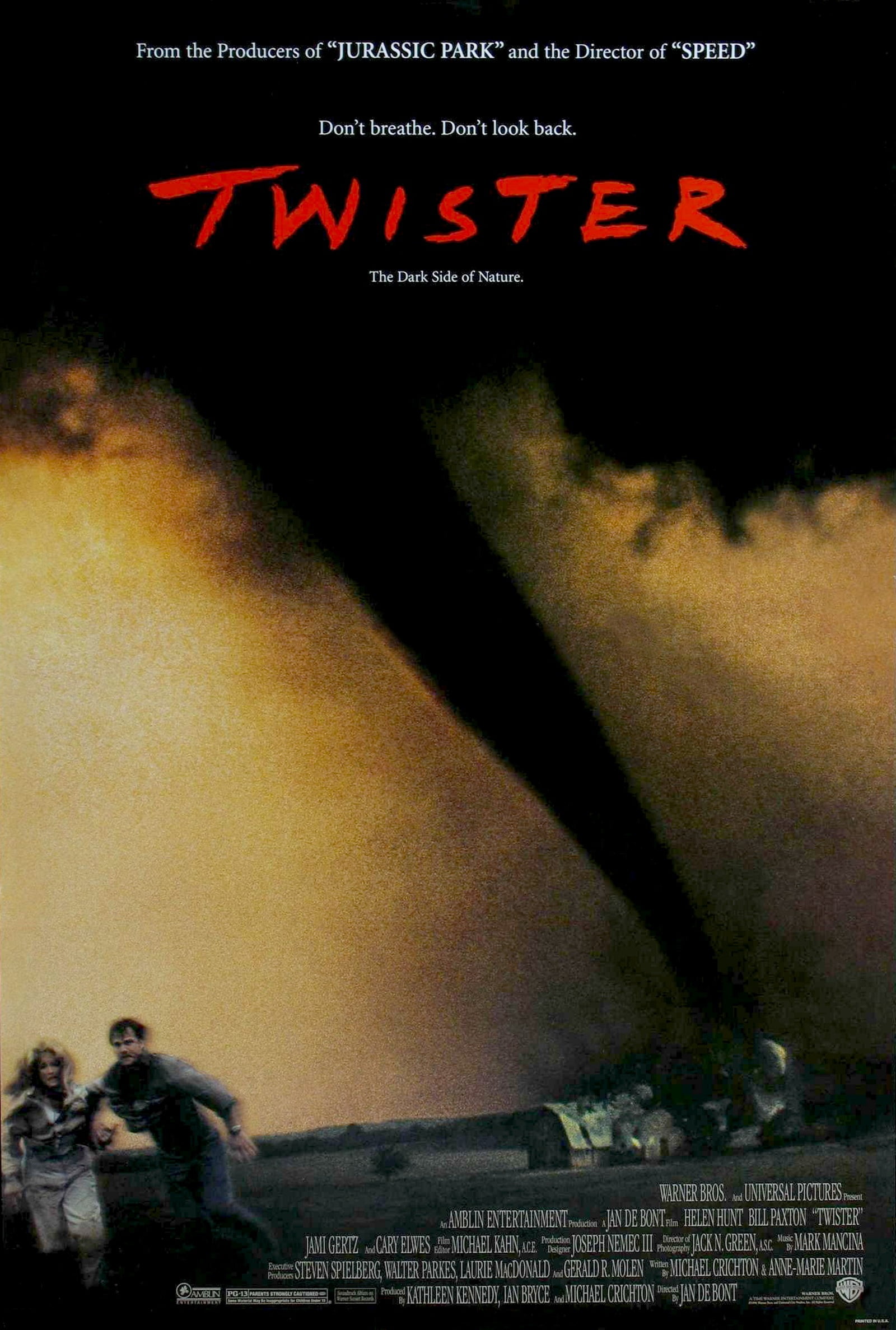

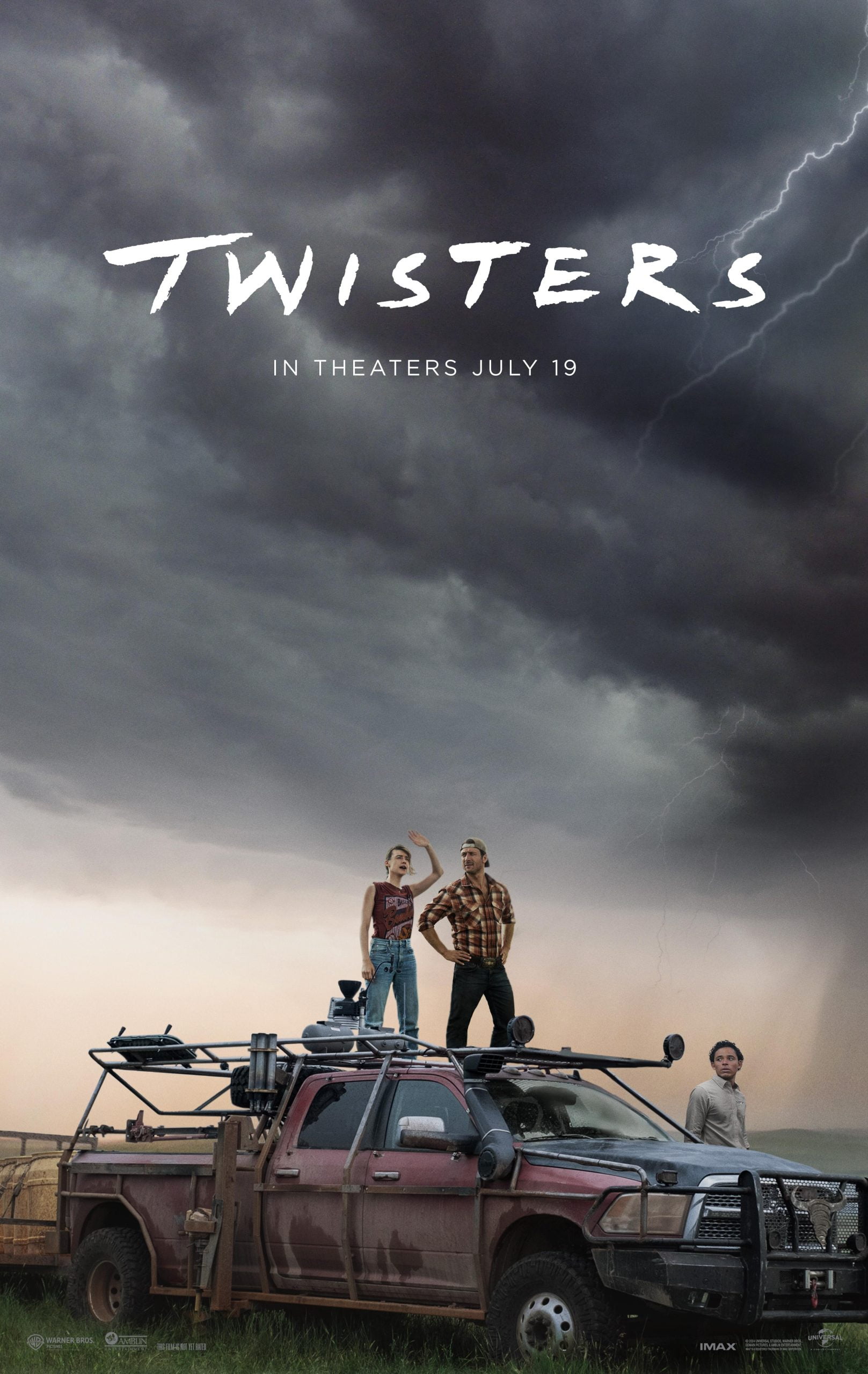

In the original Twister film, released in 1996, the core relationship of the film is not merely that of the tornado and the scientists that are pursuing it, but also between Jo and Bill, while pitting Melissa as the other woman in the relationship, who has to part ways with Bill to allow him to rekindle his failed relationship with Jo. Beyond a simple disaster film, it also features familial relationships that give it an aura of relatability: family, grief, and most importantly, love, which ultimately influences all our decisions. Twisters (2024) is also a disaster film, ostensibly about tornado-chasers in the Southern United States. Still, ultimately, it is a film about grief and love, and how people deal with, and fail to deal with, these emotions in the first place, no matter how intelligent or capable they seem on paper.

Twisters: the plot and the film

Twisters (2024) is a spiritual sequel to the original 1996 film, directed by Lee Isaac Chung from a screenplay by Mark L. Smith, produced by Steven Spielberg. It is based on a story by Joseph Kosinski. Starring Daisy Edgar-Jones, Glen Powell, and Anthony Ramos, Twisters is a story structured less around a singular, titular tornado, and more about the damage caused by the natural phenomenon, both material and emotional. The plot diverges from the formula of the original film; the protagonist (Kate Carter) is faced with tremendous loss while chasing a storm and trying to disrupt a tornado mechanism for her PhD project.

The plot diverges from the formula of the original film; the protagonist (Kate Carter) is faced with tremendous loss while chasing a storm and trying to disrupt a tornado mechanism for her PhD project.

However, instead of turning obsessed with storms as Jo Harding (Helen Hunt) in the original film; she refuses to be associated with storm-chasing any further, choosing instead to get a job with NOAA in New York. when her college friend and fellow storm-chaser Javi comes knocking with an offer she cannot refuse, Kate is forced to reconcile herself with the grief of losing three of her friends to a singular tornado, and her work, which might be able to save the lives of thousands of people. Along the way, they meet, knock horns with, and eventually befriend a ‘tornado wrangler’ Tyler Owens, a YouTube meteorologist and storm-chaser by profession.

Unlike Roger Ebert’s criticism of the original film, which said, ‘As drama, Twister resides in the Zone. It has no time to waste on character, situation, dialogue and nuance. The dramatic scenes are holding actions between tornadoes. As a spectacle, however, Twister is impressive. The tornadoes are big, loud, violent, and awesome, and they look great’ (Roger Ebert), the characterisation of Twisters (2024) is a vast improvement on the original, and most importantly, calls for a new direction in the genre of disaster films with characters that are not mere caricatures of stereotypes on the screen, and feature some degree of motivation and character development throughout the film.

For all three of its primary characters, the tornado is not merely a natural phenomenon that they are incidentally obsessed or fascinated with; there are real-world motivations, monetary and emotional, that influence their decisions and fuel their character arcs. However, to the great disappointment of viewers, the supporting characters show no character development throughout the film and remain one-dimensional until the end of the film. However, expecting a peanut gallery of supporting characters to all have fully fleshed-out character arcs is a tall order, even from director Lee Isaac Chung.

For all three of its primary characters, the tornado is not merely a natural phenomenon that they are incidentally obsessed or fascinated with; there are real-world motivations, monetary and emotional, that influence their decisions and fuel their character arcs.

For director Lee Isaac-Chung, this is his first film post the success of Minari (2020), and it is not surprising to see the influence of his previous film on his next venture; though the films do not share a cinematographer, Minari being shot through the lens of Lachlan Milne, and Twisters by Dan Mindel, best known for his work on the Star Wars Franchise, Lee’s directorial vision, having matured since Minari, calls the primary shots for Twisters.

Shot entirely on 35mm film, with Panavision and Arri cameras as well as Primo Anamorphic lenses, the cinematic visuals of the film are immense: the rolling fields of the American South, the approaching clouds, and the tornados, all form part of a spectacle that are each bigger than the last. The end result is a film that is devastatingly attractive: showcasing the extent of destruction caused by a singular natural disaster masterfully on the screen.

The acting and the dialogues in Twisters

If there are any complaints about Twisters, it is in the acting. While the three starring characters play their roles with as much panache as can be mustered in a film where the focal point is a cataclysmic disaster; the rest of the actors, having little to work with, simply show up as interchangeable stereotypes from beginning to the end. Yes, including the role of Ben, the British journalist with a stiff upper lip, played with considerable aplomb by Harry Hadden-Paton.

Twisters, having exhausted its novelty on the three main characters, resorts to mere caricatures of the secondary characters; the predictable ‘suit’ who cares less about the lives of people and more about his scientific data collection, the rocket-happy ‘Boone’, played by Brandon Perea, whose apparent sadness over Tyler’s “betrayal” of him is assuaged by the promise of firing rockets into a tornado, and so forth. Even worse, if such an adjective can be used, is the use of dialogue in the film, try as one might, viewers might not for the life of them remember a singular dialogue spoken in the film, save Edgar-Jones and Powell’s ‘if you feel it, chase it’, and Ramos’ ‘Attaboy’, both of which come at the tail end of the film.

Perhaps this is the result of watching four tornadoes devastate Oklahoma, but similar to Janet Maslin’s criticism of the original Twister (1996) film, ‘Somehow Twister stays as up-tempo and exuberant as a roller-coaster ride, neatly avoiding the idea of real danger.’ (Janet Maslin for the New York Times), Twisters (2024) steps around the idea of any real, long-lasting solution, perhaps in the danger of boring the audience with an overload of bureaucratic procedures on screen. While the danger is present, real, and quite imminent, solutions are no more present and viable than an end-credits montage.

In conclusion

While Twisters (2024) is a fun rollercoaster ride, it also deals with the very human emotion of grief, which can be debilitating to a person and their sense of self, especially if grief is mixed with guilt. The guilt of surviving, the guilt of moving on too quickly in one’s mind—you name it all, the human mind is capable of conjuring these emotions. This is the real triumph of the film, all of its credits should go to the director, the scriptwriter, and the actors, who envisioned it and brought it to life on screen. For moments, it could be thought that the film would have a serious conversation around the survivor’s guilt felt both by Javi and by Kate, but again, the film neatly sidesteps any real conversation and refuses to move beyond a singular explosive confrontation, which does not quite seem healthy.

Perhaps this is on the reviewer. Part of the viewers’ lukewarm reaction to this film might be the high hopes they had for it, after learning of its direction by Lee Isaac-Chung, whose last outing can reduce one to tears, and changed the way we view immigrant stories in literature and visual media. But even in a disaster film, Lee manages to break new ground. His capturing of Kate as a character wracked by the memory of her abject failure as a scientific researcher takes a different direction than a run-of-the-mill disaster film, and this is the hope we can have for any future exploration of this genre.

(Twisters is running in theatres now.)