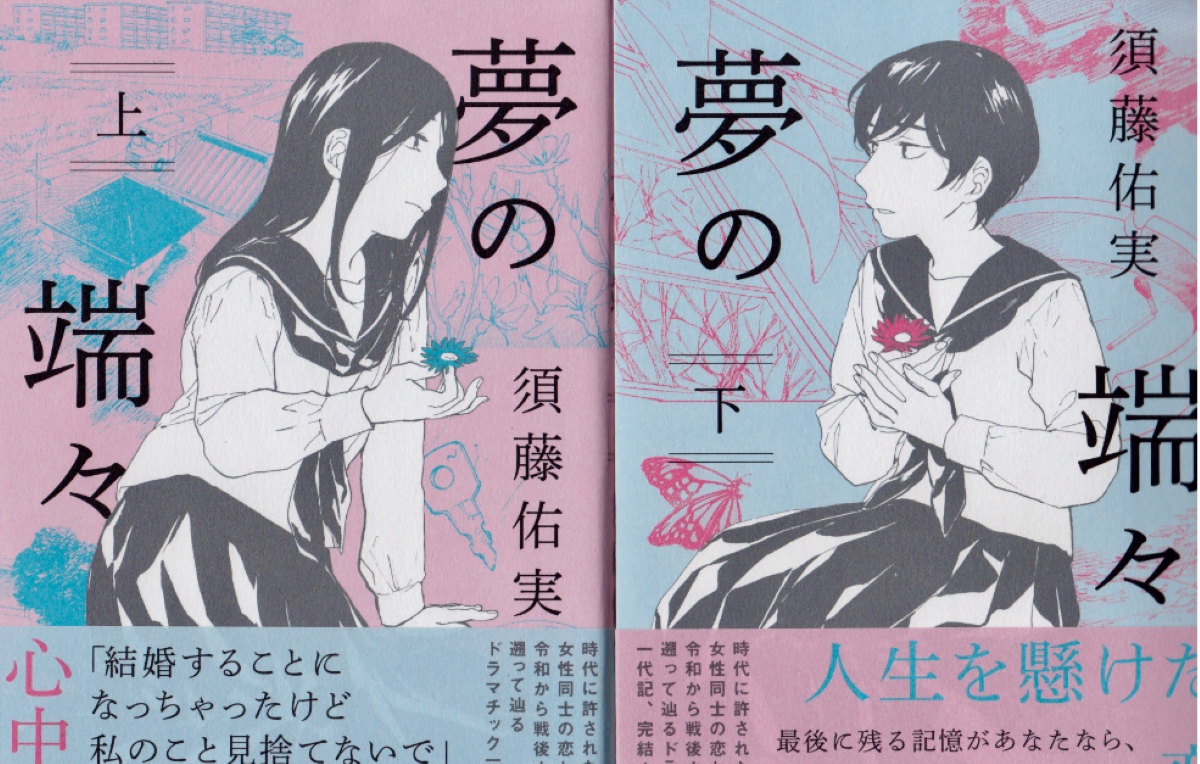

Yume no Hashibashi (The Ends of a Dream) by Sudou Yumi is a Japanese graphic novel. The story is centred around two women, Itou Kiyoko and Sonoda Mitsu. Yume no Hashibashi starts with a heartbreaking insight into their lives: Kiyoko is a great-grandmother who seems to be on the brink of dementia. She mistakes her granddaughter for her daughter and often forgets that the child in their house is her great-granddaughter. Mitsu has a plethora of health problems and has undergone extensive treatment for them but to no avail.

At 85, the two women express longing for the life they could have had together if they had been born in the relatively accepting atmosphere of today’s world. After all, Kiyoko’s memory does not fail her when it comes to the one person she has truly loved – Sonoda Mitsu. This longing must not be mistaken for regret: Mitsu makes it clear that had they been born a little later or in another place, they might not have met at all. And for her, that would be the greatest tragedy of all. Before Mitsu’s sudden demise at the end of the first chapter, she promises Kiyoko that she will remember their life on Kiyoko’s behalf – the rest of the novel is Kiyoko’s fulfilment of this promise in Mitsu’s place.

Queer temporality, non-linear narratives, and memory in Yume no Hashibashi

While the story begins in 2018, the narrative follows a reverse chronological format. We meet the characters in their old age, right before Mitsu passes away. By the time we bid them farewell, they are teenagers again. This narrative choice imitates a key feature of memory: we look at moments gone by with a shadow of what’s to come; the past becomes a painful reminder of what our present has become. But, memory can be retrospectively moulded and wilfully remembered in certain ways. This way of remembering and narrating is important when one looks at the novel through the lens of queer temporality.

Disruption of the linear form of narration, according to Jason Palmeri, among other theorists, is a form of rebelling against the heteronormative structures of literature. Time, in simple words, is felt much differently by queer people than it is by heterosexual people. Thus, as explained by Dustin Goltz, the progression of life measured with reference to goalposts like marriage, followed by children, and family inheritance is a heteronormative construction. This is in part due to the experiences of marginalisation and discrimination, leading to queer people feeling like their goalposts in life were achieved much later when, in reality, heteronormative societal structures do not account for differing life experiences. Thus, queer temporality seeks to realign the seemingly linear relationship between the past, followed by the present, and the anticipated future.

Richard Sawyer, in his essay “Queer Narrative Theory and Currere: Thoughts toward Queering Currere as a Method of Queer (Curricular) Self-Study” introduces the concept of currere. Building upon the idea of queer temporality, currere is a literary form that finds a new way of engaging with autobiographies without following the framework of storytelling that heterosexual stories do. It is “a critical form of autobiography […] that examines the curriculum of everyday life [and] one‘s process of engagement within [their] contingent and temporal cultural webs”. This allows the narrator to revisit and reexamine their “personal history when that history was erased or rendered invisible in the past.”

Since the first few chapters, Kiyoko and Mitsu’s story is shrouded in mystery. Under what circumstances did they form their friendship in school? How did they come to realise they loved each other, and what were the series of events that prevented them from living together? Over the years, several versions of their story have been discussed by their peers and misunderstood by Kiyoko’s granddaughter, but never spoken of by the two lovers.

The novel, Yume no Hashibashi, however, is Kiyoko’s account and reflection of the intimate parts of their relationship. After Mitsu passes away suddenly, Kiyoko reflects on the life they have led thus far. In doing so, Kiyoko realigns her and Mitsu’s story by making their past her current reality. Once she believes she has fulfilled the expected role of a wife and mother, she revisits the moments she wished she had lived differently that are vivid in her memories. By bringing the hidden ‘truth‘ to light, Sudou Yumi masterfully allows Kiyoko to at last be the narrator of her own experience.

What do life and death mean in the face of love?

In Chapter 2, which details their life in 1988 in their late 50s, Kiyoko and Mitsu discuss that the former wishes to separate from her husband. She states that she has fulfilled what she ‘needed‘ to do, and can now ‘move on with her own life.’ Later, in Chapter 4, she expresses that the love and bond Kiyoko and Mitsu share goes far beyond what can be contained by the institution of marriage. Yet, the pressure they both face to uphold and continue their family name (Kiyoko, due to her age and Mitsu, due to the death of all her elder brothers in the war) is not sidelined in Yume no Hashibashi.

Kiyoko, in her 20s, believed that she had failed everyone in her life and the way to rectify her shortcomings was to marry the man her parents wanted her to. Here, the illusion of marriage as a safety net or convenience for women is shattered. It is revealed to be nothing more than a form of self-inflicted punishment in the face of perceived failure. What makes her ‘decision,’ all the more bitter, is the subsequent revelation of the promise Kiyoko and Mitsu made to each other as young women: neither of them would ever get married since they could not be with each other. No matter how much Kiyoko and Mitsu love each other, their only choices are to live and die alone or to marry a man and subject themselves to domestic life.

Unfortunately, once Kiyoko confesses to Mitsu a few years later that she must get married, Mitsu’s questionable perception of her lover is brought to light. She views Kiyoko as a possession that follows the traditional transfer of ownership after marriage – once Kiyoko is married, she is no longer ‘hers.’ Such language disturbs Kiyoko, who then rejects all affection from Mitsu. This is a direct reflection of how Kiyoko’s husband treated her – intimate relations were a way for him to ‘try her out,’ and, as mentioned, Kiyoko only gives in because she believes she is worthless. Mitsu fails to understand that this marriage is not a decision Kiyoko makes – all ‘choices,’ aren’t inherently empowered. Kiyoko’s emotions are drained over the years of marriage, caused by her family’s misunderstanding of her life as a happy one and her husband’s adultery. Eventually, she relegates herself to the life of a lonesome housewife destined for perpetual misery.

Ironically, their attempt to die by suicide in their teenage years (revealed in Chapters 8-10) was an attempt to prevent this very passage of ownership. After the two form a friendship they believe is unlike any other they have known, Kiyoko highlights a key reality of their lives. As women, they are thought to be first owned by God, then by their parents, and eventually by their husbands. She suggests that before their husbands come into their lives, the two girls should erase themselves from this world. Their attempt, however, is unsuccessful. When they wake up, Kiyoko laments the generational fate that awaits her, that no woman in her family has been able to avoid. What follows is a particularly painful realisation, both for Kiyoko as she reminisces, and the reader who knows the future of the lovers. Mitsu’s naive hope leads her to promise Kiyoko that they will work hard for each other to escape this fate. Their dreams are made up of olive gardens and a blissful life in a quaint home.

While painful, this dream is full of hope uninterrupted by the omniscient narrator, unlike before. What stands out is the courage to dream in the face of such a cruel fate. Their dream is never realised; yet, is their hope futile? Forgetting their hopes in the course of life would have been an act of conformity, but so long as they have memory, it may yet do them good.

Another focal point here is the power of words exchanged between them. In certain instances, their secret conversations are a source of strength. But words also fail them and make them believe their life is to be lived in a predetermined manner. The role of books as Institutional State Apparatuses is not ignored, but their dreams are not rendered unimportant either, primarily in Chapter 9: “Not one book or person said I could fall for a woman, yet here I am, in love with you. And all that preaching about love in death? To hell with that. Kiyo-chan, I want to live for your sake instead.” Thus, Yume no Hashibashi works in defiance of the ‘burn your gays’ or ‘dead lesbian syndrome’ trope employed by many queer stories; the two leads do not die out of their love for each other.

The reminder of their love for and promises made to each other is present in their very bodies. They both lost one of their pinkies that fateful day. In the end, when Kiyoko finishes reminiscing and leaves her house, she sees the late Mitsu as a young girl in an open field. She proceeds to leave with Mitsu, herself a teenager again. What became of the old women remains unknown to their families and the reader – all we can do is speculate. Finally, they are free to live their life away from the prying eyes of the world.

The novel, Yume no Hashibashi, leaves the reader with multiple questions and emotions. Foremost is one that Kiyoko asks Mitsu in Chapter 1: was their encounter a blessing or a curse? Is it fair to categorise their relationship as either, or should they be allowed nuance unconditionally available to other stories? Should they have never dreamed of a better future for themselves if they were unable to realise it in the course of their life?

About the author(s)

Aaliya Bukhary (she/her) is student of Economics student based in Mumbai. She is passionate about merging data analysis with her love for writing, and aspires to empower through information. Aaliya also has a fondness for cats and enjoys listening to Mitski!