Amidst the changing climate, Odisha’s Chuktia Bhunjia tribal women are fighting food and nutritional insecurity by going back to their roots, reviving traditional crops and forest food.

Chuktia Bhunjia belongs to one of the Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs) who live in Odisha’s Nuapada district, which comes under the Eastern Ghats region. Subsistence rainfed agriculture and collection of wild food items have been mainstay of their food system and livelihood for years. But not anymore.

Subsistence rainfed agriculture and collection of wild food items have been mainstay of their food system and livelihood for years. But not anymore.

‘Earlier, around 20 years ago, rainfall during the monsoon was plentiful and regular. We used to harvest bumper yields from our farms,’ recalled Champa Bai Barik, (72), a Chuktia Bhunjia woman at Cherichuankhol village in Komna block under Nuapada district. But these days, rainfall is erratic and unpredictable. Harvest from agriculture is not adequate. Food hardly lasts for 6-7 months in a year, she added.

Traditionally, the Bhunjia community follow a mixed system of farming, where they grow indigenous varieties of millets, pulses, cereals, oil seeds, legumes, vegetables, tubers and roots. ‘These crop varieties have been grown by our forefathers for centuries,‘ said Malti Bai Bhunjia, (77), at Lanjimar village in Nuapada block. They are resilient to less and erratic rainfall. ‘Earlier, we faced severe droughts. But they would withstand each time. They are also nutritious. But they fetch less market price. That’s why we replaced these crops with high yielding paddy,’ she explained.

According to Bhunjia women farmers, hybrid varieties of paddy have the potential of high yield with an assurance of minimum support price. The flip side is that they cannot withstand climatic exigencies. Nuapada has a history of extreme heat conditions. The district witnessed severe droughts in 1972, 1996, 2000 and 2002.

Over the years, shifting from the traditional mixed system of farming to mono-cropping has further increased farmer’s vulnerability to climate change. This has also worsened the nutritional security of the community. Nuapada has reported a high rate of distress migration as vulnerable households find it difficult to cope with the climate change. However, the impact of climate change is more pronounced among the Bhunjia women.

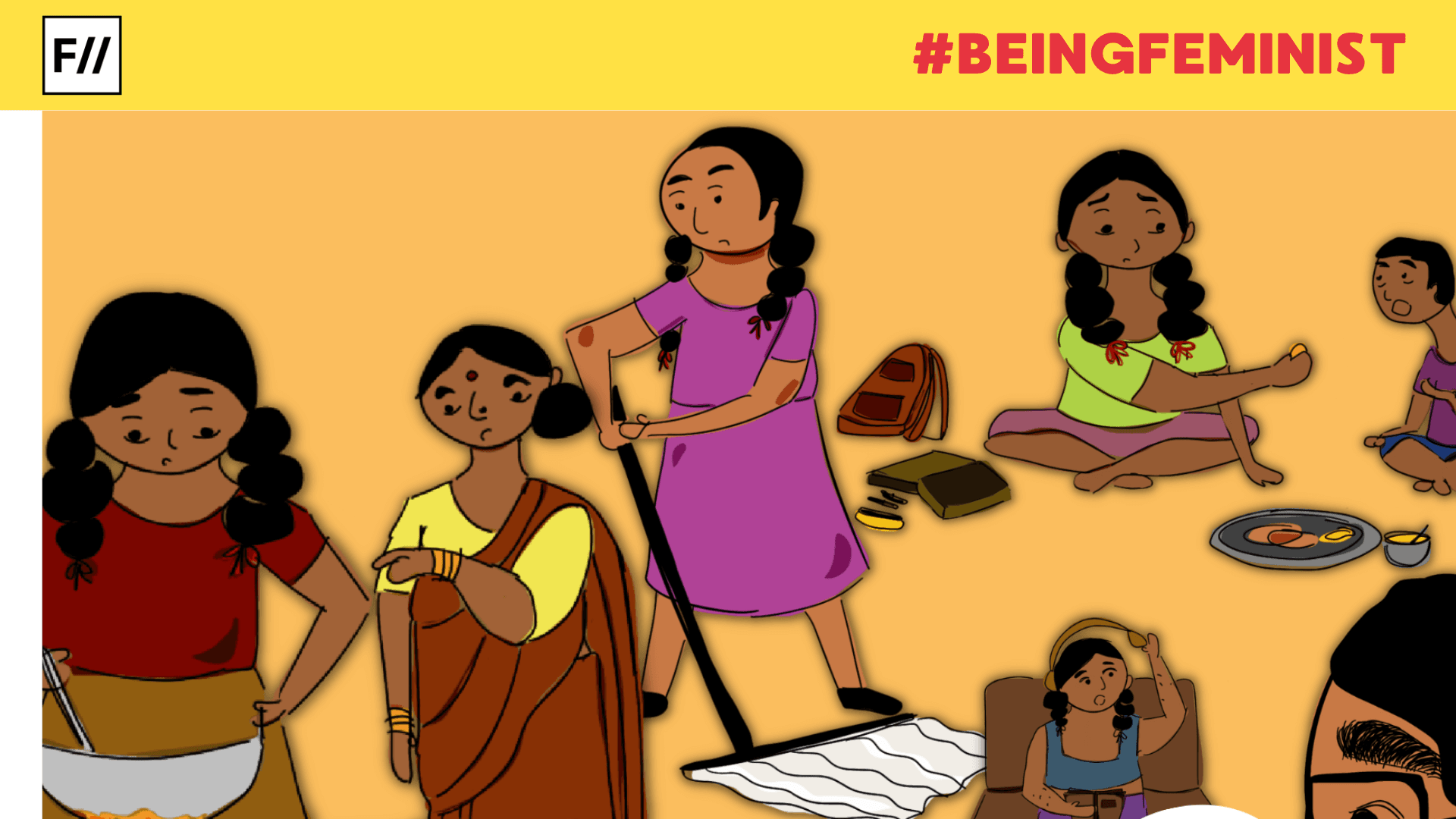

Bhunjia women suffer the most

Since the migration rate is increasing, where male members of the Bhunjia households work in neighbouring states, agriculture work at villages is mostly done by women. ‘In the absence of our male counterparts, we execute all major agricultural operations,’ said Gomati Jhankar, (61), at Cherichuankhol village, adding that, ‘This has increased our workload. We suffer from persistent backaches and body pains.’

When agriculture fails due to climate change, women often engage in labour work in nearby villages to supplement their household income.

When agriculture fails due to climate change, women often engage in labour work in nearby villages to supplement their household income. ‘It is like a triple burden for us,‘ said Laxmi Bhunjia, (54), at Jalmadhei village in Komna block. ‘First, we work hard on our farms. Second, we work as manual labourers. Third, we take care of our children and elderly people at home. In addition, we do other household chores like cooking, fetching drinking water, cleaning utensils, washing clothes‘, she added.

‘Women are extremely sensitive to food insecurity and nutritional deficiencies,’ said Rukmini Rao, a gender specialist who works with Mahila Kishan Adhikar Manch. ‘They need nutrient dense food during menstruation, pregnancy and lactating. Their health is further threatened when climate change adversely impacts agricultural yields,‘ she added. Phulmati Patia at Jalmadhei agrees. She said, ‘I feel more stress to deal with food shortage. Our children become weak when the harvest from the farm is less.’

Reviving ancient crops

Against all these climate induced challenges, Bhunjia women are reviving their traditional crops under diverse cropping to safeguard against nature’s vagaries. Basing upon climatic suitability, in the first monsoon during June-July, they start agricultural work like ploughing the land, fencing and sowing seeds. They grow around 12-16 types of crops under a mixed system of farming. ‘We sow traditional varieties of millets like ragi, foxtail, little and sorghum. Along with this, we also sow kandul (Arhar), biri (black gram), kulath (horse gram), maize, and jhunga (cow pea),‘ said Biyayi Bai Bhunjia at Kotrabeda village.

Local varieties of paddy such as lachei, kalikhuji and jhuli have been revived and shared with farmers from the community. Biyayi says, ‘Our traditional varieties of paddy require less water and manure. They are short duration, harvested between 60 to 90 days of sowing. They are tasty. And can be preserved for a long duration.’ On the other hand, hybrid paddy, she claims, ‘Are vulnerable to erratic rainfall. They need expensive fertilisers. They also don’t have a long shelf life.’

Biyayi says, ‘Our traditional varieties of paddy require less water and manure. They are short duration, harvested between 60 to 90 days of sowing. They are tasty. And can be preserved for a long duration.’

Agriculture in the Bhunjia community is deeply associated with several rituals and offerings to appease local deities. ‘We pray to Bhima (rain god) and Chorokhuntein (goddess of good harvest) for good rainfall and bounty of harvest,‘ said Basanti Bai Bhunjia at Kotrabeda. ‘We seek divine blessings from our goddess Gangadi for a disease-free yield. Every year, we appease her with offerings of food, traditional liquor, and sacrifice native roosters‘, she explained.

The Bhunjia community applies dry cow dung as manure for the soil. Under the traditional system of mixed farming, harvest time for each crop is different. ‘Harvesting crops is a meticulous process. Some crops mature early, while some take time. We carefully harvest crop after crop without damaging other standing crops. Even if rainfall delays, or pests damage any crop, we have many other crops to survive on,’ narrated Jaila Bai at Kotrabeda. This system of farming has evolved in sync with nature having climate resilience integrated with it naturally.

Regular consumption of traditional grains like millets, pulses, and cereals could substantially increase dietary diversity, as well as strengthen food and nutritional security among the Bhunjia community, especially pregnant and lactating mothers, children and elderly people. ‘Our forefathers were strong. They lived long. Because they used to eat our traditional food,’ said Hansta Barik at Cherichuankhol village. Our food plate is more colourful and diverse today. We have reintroduced our traditional crops, she highlighted.

Unlocking forest food

For years, wild edible food, deeply rooted in local culture and practice, has constituted an integral part of the food system among the Bhunjia community. Traditionally, women spend hours foraging wild mushrooms, berries, fruits, tubers, roots, greens, and edible insects in the forest.

‘For us, forest is like a hidden treasure,‘ said Jilla Bai Bhunjia at Kotrabeda. ‘When I was around 8-10 years, I used to venture into the forest along with my mother. She taught me what is edible and what is poisonous. And that’s how I learned the harvesting season of different wild foods. There is always food in the forest round the year‘, she recalled.

Wild fruits like kendu (persimmon), chahar (chironji), amla (Indian gooseberry), buer (jujube), mahul (madhuca indica) are sun dried to preserve it for consumption during off season. After sun drying, it is kept inside bags made of siali (Bauhinia yahi) or palasa (Butea monosperma) leaves. These bags are then hung on the roof in the kitchen. The smoke from firewood chulah helps to keep insects away from the bags and thus ensure long term preservation of its content.

Buer pitha is one such traditional recipe. To prepare this recipe, ripe buer is sun dried. After that seeds from buer are removed. The dried buer is then hand pounded to make powder. Salt and chili powder is added into the liquid jaggery. Then buer powder is added into the jaggery. It is cooked till it turns into a paste which is used to make a circle shaped pitha. This pitha is then sun dried and stored in the kitchen. When needed, Buer pitha is fried with oil and consumed.

Kuchei kanda Jhol is yet another delicacy of the Bhunjia community. It is made from a wild tuber called kuchei kanda. First, the tuber is washed with water. Then its skin is peeled. After peeling, the tuber is cut into small pieces and boiled in a pot. After that, put oil in a pan. Add coriander, mustard, garlic paste and dry chilli in the hot oil. When this is fried well, put it into the pot containing boiled tubers. Finally, add tamarind pulp, salt, black pepper powder, turmeric and cook it for 10-15 minutes.

‘At a time when climate change ravages rainfed crops, it is wild foods that ensure food and nutritional security of vulnerable tribal communities,’ said Professor Ashwini Chhatre, Indian School of Business, Hyderabad. Forged food is essential for tribal women’s nutrition. It contributes to their dietary diversity, especially during food scarcity periods when the crops are not ready for harvest, he added.

‘At a time when climate change ravages rainfed crops, it is wild foods that ensure food and nutritional security of vulnerable tribal communities,’ said Professor Ashwini Chhatre, Indian School of Business, Hyderabad.

Bidhilata Roy is a development professional who has worked extensively on women’s health and nutrition management in Odisha’s tribal areas. She said, ‘Traditional knowledge of tribal women on wild foods, passed down through generations, is gradually eroding. It is high time to document many neglected wild foods, their seasonality, distribution, and nutritional value. This knowledge should be systematically promoted or upscaled and incorporated into diet diversification policies.’

Vasundhara is a Bhubaneswar-based NGO that works on natural resource governance and sustainable livelihood in Odisha. According to Y. Giri Rao, Executive Director of the NGO, for centuries tribal communities have adopted a low-carbon footprint lifestyle that has immensely conserved biodiversity. Unfortunately, he said, ‘In many tribal areas, women face severe challenges to access, consume and transport wild edibles. Government should recognise their legal right to access non-timber forest products.‘

About the author(s)

Bhubaneswar-based independent journalist. For over 10 years, Abhijit has reported on sustainable food, health, livelihood, women's right and climate change with a special focus on tribal and other marginalised communities in India and Cameroon.