Bollywood films are extremely biased in favour of the upper castes in India. The cinematic (mis)representation of the Dalit community, the dearth of Dalit actors and directors, and the absence of caste issues in the film plots reinforce caste within mainstream cinema. The politics of spectatorship born out of this asymmetry strengthens caste stereotypes of Dalits.

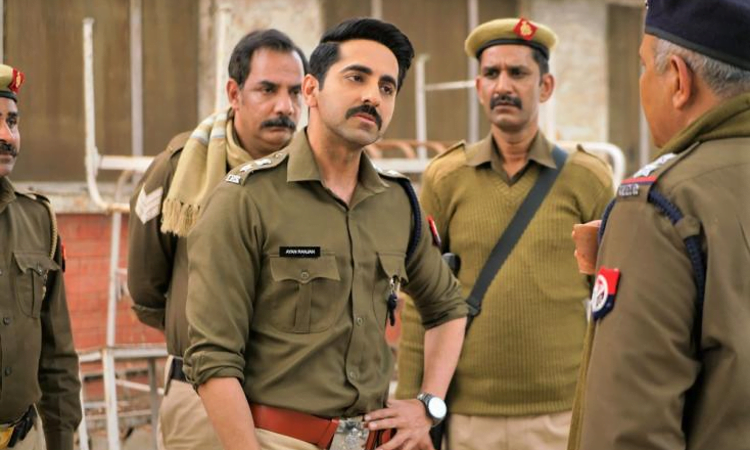

Mainstream Indian cinema presents the Dalit identity as something despicable, something unworthy of existence in the cultural spheres by portraying Dalits as passive subjects of oppression who are always waiting with folded hands for a Savarna saviour. The film Article 15 by Anubhav Sinha is an important manifestation of this, wherein a Brahmin police officer is portrayed as the sole messiah of the Dalits. Often the filmmakers fail to understand caste as a structure.

The biopic of Jyotirao Phule ‘Satyashodhak,’ treats the Brahmins as evils in their dispositions rather than questioning caste as an institution. The autonomous Dalit voices are curtailed severely through the hegemony of savarna ideas in filmmaking. Recently a wave of Tamil radical anti-caste films has been made by directors hailing from Dalit communities that have challenged this unequal politics of portrayal.

The apparatus of Dalit exclusion

The renowned Dalit scholar Suraj Yengde explains the structural causes of the invisibility of Dalits in the Bollywood Film Industry in his seminal essay Dalit Cinema. He traces the historical and cultural context of filmmaking in India. In the post-independence period cinema played a significant role in cultivating ‘nationalist,’ sentiment which involved romanticising the agrarian society and later the military. This project has been achieved by blurring the reality of caste-based oppression and denying the role that caste plays in generating graded inequalities in Indian society.

Yengde further explains the erasure of caste from the silver screen by pointing out that the broader category of poor and marginalised has been used to mask caste identities and hierarchies resulting from them. Thus class centredness helps in the sidelining of caste oppression.

His paper also tells us how the Bollywood reproduces stereotypes about Dalits. The protagonist in most films is fair-skinned and hails from a dominant caste background while the Dalit characters, in the rare cases they appear, are dark-skinned and are usually rouge elements like thieves, criminals and gangsters. Even films like Gangajal, Jolly LLB 2, and Jawan that do talk about social issues remain silent on caste and have the lead roles being performed by dominant caste actors portraying dominant caste characters.

In Jolly LLB2 the protagonist flaunts his Brahmin status before the judiciary. The Central Board Of Film Certification also plays a role in silencing Dalit voices by censoring films that question caste. The late director SP Jananathan’s action-adventure film Peranmai underwent 16 cuts as directed by the CBFC. The director was reportedly told that it was not necessary to depict caste in cinema because it supposedly did not exist in recent times.

Caste and resistance from Tamil Cinema

The problem of casteism is not absent in Tamil cinema yet the resistance to it comes most vigorously from Tamil cinema as compared to other regional cinema. In Tamil films, Dalits are presented as filthy individuals with a poor sense of manners. In Tamil Nadu, it has been customary until recently that Dalits not be allowed to wear ironed shirts or sport stylish moustaches. This trope has been reproduced in films where characters who were well dressed in clean clothes or dressed in all white were given maximum screen space. Dalit individuality and lives were largely the scope of comedy and jokes which had latent casteist overtones.

The resistance to Brahmanical hegemony in Tamil cinema began with the growth of the Dravidian movement in the 1950s which used cinema as a mass medium to promote Tamil cultural identity and oppose Brahmanical domination. The Dravidian movement used literature, drama, and films to propagate its message. Many prominent personalities of the movement like M.G. Ramachandran and Muthuvel Karunanidhi were part of the film industry.

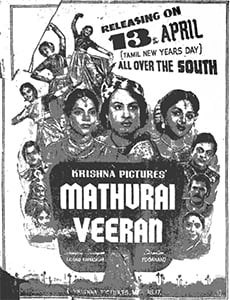

The film Madurai Veeran (1956) spearheaded the discussion around caste issues. The story involves a man from a lowered caste who rescues a princess but later is ostracised for violating the caste codes around touch. This film ensured the enormous popularity of its principal actor and later the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, M.G. Ramachandran a popular figure among the Arunthathiyar, a major Dalit Community in Tamil Nadu. Other major anti-caste radical Dravidian-themed films produced during this time are Penn (1954), Thaikku Pin Thaaram (1956), and Thayilla Pillai(1961).

Thayilla Pillai was written by Muthuvel Karunanidhi the late leader of DMK and another former Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, whose 1952 film Paraskathi brought about radical Dravidian ideology in mainstream cinema.

This revolution was followed by an ideological counter-revolution in the 1990s due to a wide swathe of film catering to the dominant castes like Kallars, Thevars and Gounders. Films like Chinna Gounder, Periya Gounder Ponnu, and Thevar Magan openly celebrated dominant caste pride by portraying dominant caste landholders as benevolent beings always extending their helping hands to the Dalit peasants and agricultural labourers. This trend occurred due to the movements of the dominant castes in the 1990s in response to the implementation of the Mandal Commission recommendations. The Dalit as a subject was again subsided.

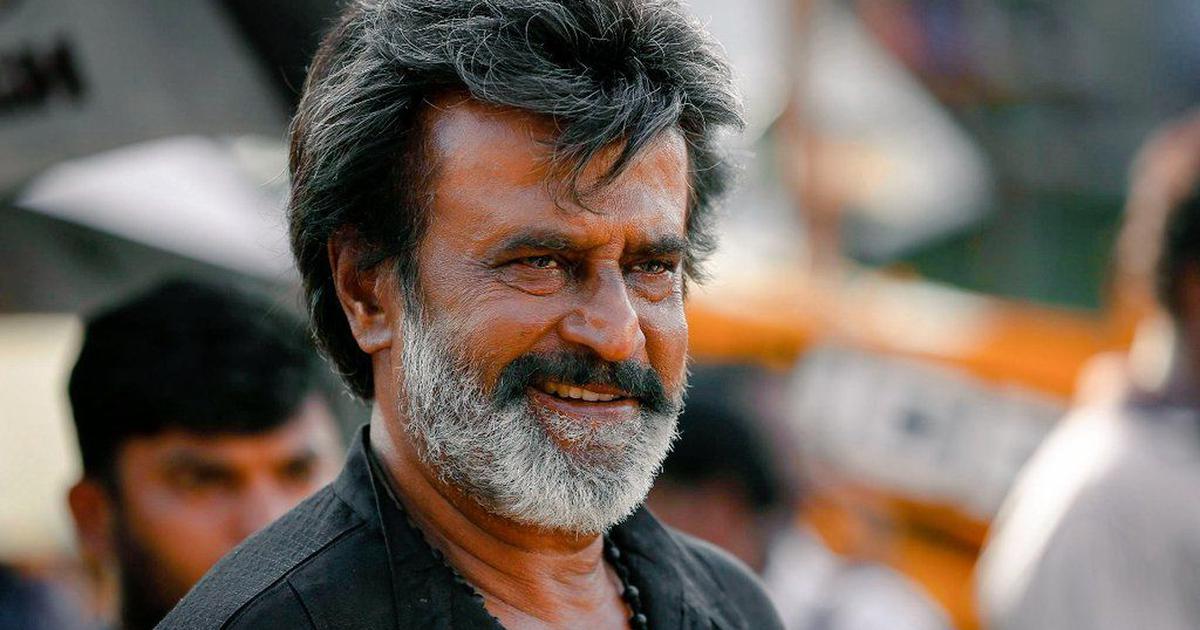

The new millennium saw the assertion of radical Ambedkarite voices in Tamil cinema with the entry of Dalit film directors like P.A. Ranjith and Mari Selvaraj who made critiquing caste the central tenet of their works. P. A. Ranjith’s landmark films Kabali (2016) and Kaala (2018 ) starring Rajnikanth made dressing an act of dissent. As Bell Hooks pointed out unpermitted acts of looking by black slaves served as metaphors of dissent during the period of slavery in the United States. The black people were not permitted to look into the eyes of their white masters and subversion of these rules were avenues of resistance at times when other modes were impossible. Dress for the Dalit community becomes a conduit of resistance. In Kaabali the principal character Kaabali asserts proudly his identity by wearing a three-piece suit in line with Dr B.R. Ambedkar’s call for Dalits to challenge Brahminical injunctions on dressing.

In Kaala the Periyarian theme of Dravid identity is channelised by glorifying the colour black. The protagonist Kaalikadan or Kaala dresses up in all black and leads the working class of Dharavi slum in Mumbai against eviction. There are multiple moments in the film where the docile trope imposed on a Dalit is challenged. When Kaala blocks the exit of Hari Dhada played by Nana Patekar from Dharavi and the latter is compelled to seek humbly Kaala’s permission to leave is a moment where the Dalit’s rage acquires a political connotation for the Dalit becomes a subject possessing enough agency to refuse, to challenge and bring down the citadels of oppressive Brahmanical power. This theme is further explored in the encounter between Hari Dhada and Kaala when Kaala brings out the notion of blackness as the colour of the proletariat and even challenges Hindu religious mores by saying “If depriving my people is your religion and is sanctioned by your god, I swear I will not even spare your god.”

Kaalikadan is the name of a folk deity of Tamils and the director asserts Dalit culture and identity through Kaala. In Asuran (2019), the Dalit is not a passive recipient of oppression but an active agent who fights for his dignity by any means necessary. In Pariyerum Perumal, Mari Selvaraj shows the brutal forms of oppression on the scene when a dog from a Dalit neighbourhood is killed for entering a dominant caste neighbourhood.

The major limitation of these films is that they fail to look into the question of gender. In most films, the protagonist is a cis het man while women are not provided much screen space. Women are usually shown performing traditional household chores and obeying their husbands upholding the Brahmanical trope of a good wife.

Tamil cinema thus has an emancipatory potential to create ripples of dissent especially when films are being used by Brahmanical Fascist forces to advance their agendas. At this juncture, filmmakers who want to give rise to a stream of cinema that is outspoken and critical of the status quo need to enter into a dialogue with anti-caste Tamil filmmakers and collaborate with them to give rise to an autonomous movement of Independent cinema.

About the author(s)

Rohin Sarkar (preferred pronouns: he/him) is an eighteen year old teenager obsessed with critical theory, Anarchist studies and Ambedkarite literature. His passion other than academics include poetry by Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Habib Jalib along with Anarchist punk by David Rovics. He also enjoys Oxford style and British Parliamentary debating because it enables him to speak his mind without fear of being censured. When not studying or debating he is chatting on politics with his friends either on WhatsApp or in the college premises.