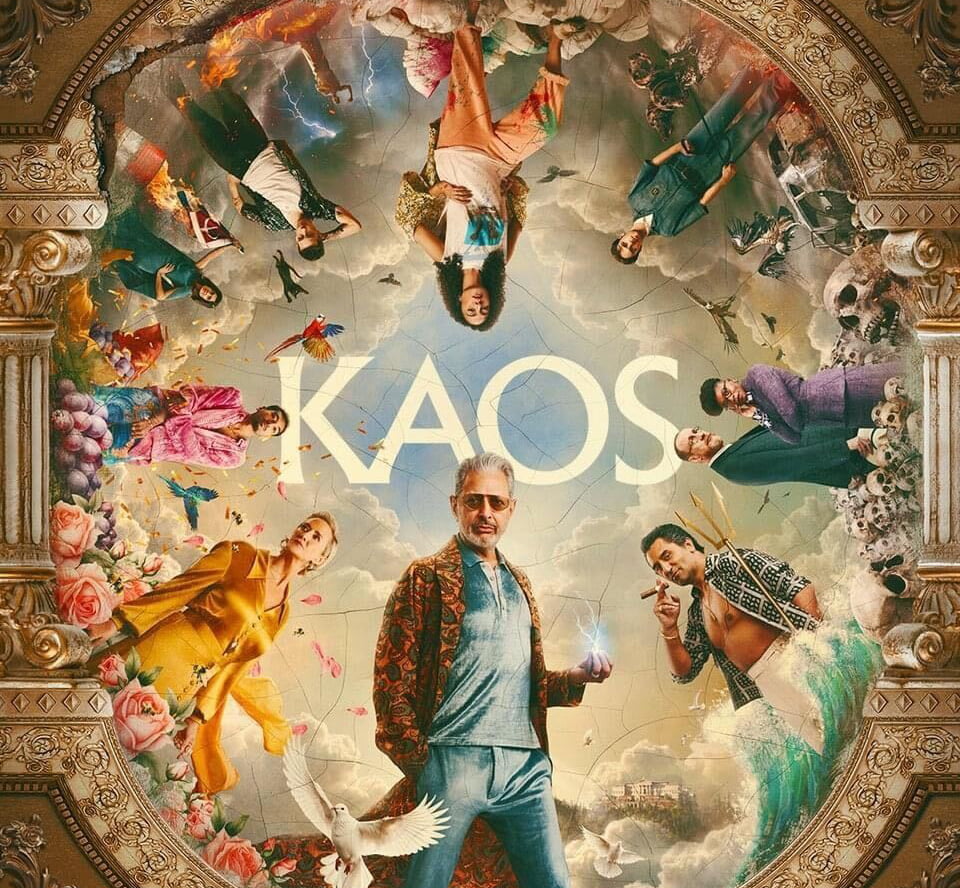

The ignominious and glorious gods of Mt Olympus come back to our (Netflix) screens to tell the same story with more than a few tweaks – in a quirky and dark package against the setting of a retro-authoritarian genocidal modern state. Sounds familiar? Kaos, a British mythological black comedy television series created by Charlie Covell, released a few weeks back and has quickly created a buzz, albeit niche. Kaos is much more than the dysfunctional family drama trope or the violence unleashed by an insecure megalomaniac ruler. It is a cathartic watch attempting to redeem the frustratingly misogynistic canon while making a not-so-subtle commentary on global politics.

A line appears, the order wanes, the family falls, and Kaos reigns

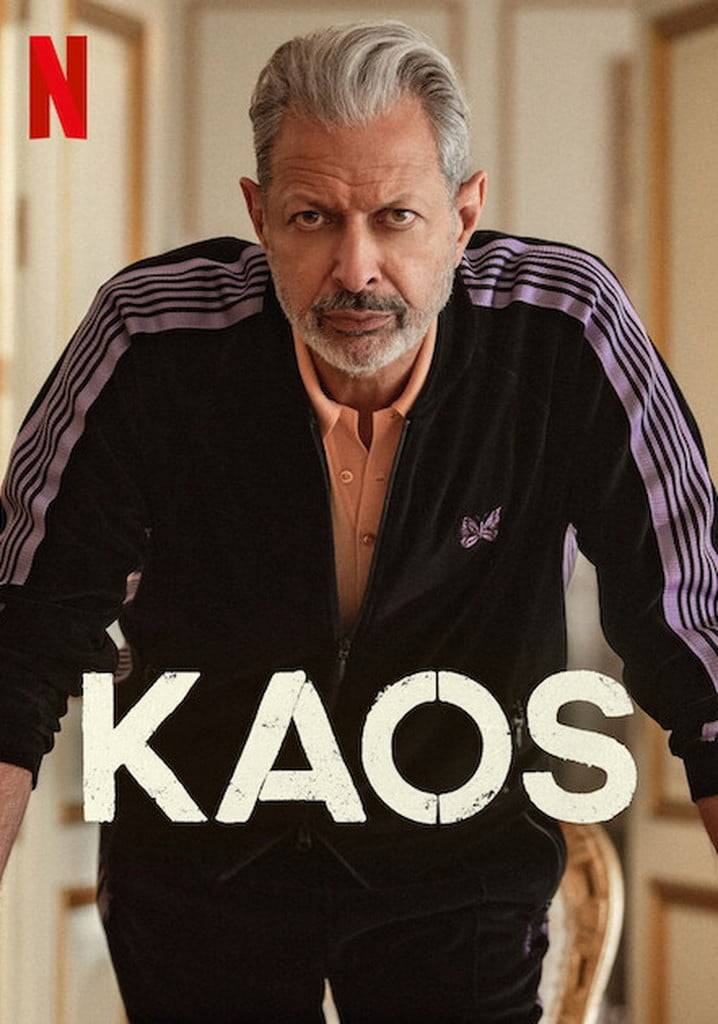

Jeff Goldblum stars as the ‘transcendent unmitigated bastard‘ – Zeus, the charming and sinister douchebag. The show opens on Olympia Day in Krete, celebrating Zeus, who notices a blip in the Meander—a divine immortality structure, causing him to completely flip out. On the same day, rebels desecrate his monument with graffiti and literal excrement, scrawling ‘Fuck the Gods,’ the series’ central theme.

Jeff Goldblum stars as the ‘transcendent unmitigated bastard‘ – Zeus, the charming and sinister douchebag.

Cliff Curtis’ Poseidon, laid-back in Hawaiian shirts but equally ruthless, and David Thewlis’ philosophical, morally superior Hades, stand in contrast to Zeus. Janet McTeer’s Hera, Zeus’ wife (and sister), is the Goddess of gods and also a morbid beekeeper, punishing Zeus’ lovers by turning them into bees, aided by her tongue-less worshippers, the Tacitas.

Stephen Dillane narrates as Prometheus, entertaining but a bit too cheerful for someone eternally punished. Nabhaan Rizwan’s Dionysus plays the desperate runt, seeking Zeus’ approval, while other gods and demigods, including Icarus and Calliope, make appearances. However, Hestia is notably absent. The prophecy that ‘a line appears, the order wanes, the family falls, and Kaos reigns‘ drives Zeus into paranoia.

The fresh twist is that Zeus may not have always been immortal, fearing his downfall, which is tied to three humans: Ariadne or Ari, Eurydice or Riddy, and Caeneus (born as Caenis) – the three rebranded characters from classical Greek canon bring focus to the queer-feminist edits. Add to that the literal three Fates and the three Furies – both trios visually coded and effused in queer euphoria.

The three mortals of Krete: Eurydice, Caeneus, and Ariadne

The first character is Eurydice, now Riddy, a human in Krete unhappily married to Orpheus, a famous singer who overplays her role as his muse. Instead of a snake bite (as was the classical canon), Riddy is hit by a truck branded “Serpent Solutions” after blaspheming at Hera’s court, where her mother, a Tacita, is an extremist worshipper. She ends up in the Underworld, stuck in Asphodel for 200 years because Orpheus stole her coin, echoing the classical myth where Orpheus’s obsession with retrieving her leads to tragedy. As Orpheus sings, ‘Is it a little bit much… Under the weight of this love?‘, the audience cannot help but vigorously nod.

At Asphodel’s middle-management corporate office, she meets our second character of importance – Caeneus. Born an Amazon (a wild card entry into the classical canon) Caeneus is ousted from the community for identifying as a man – a TERF narrative that reflects the bitterness and ego of transphobic empowered cis-women. In a heart-warming and painful scene with his mother, Caeneus tries denying his identity so that he can stay home when his mother says ‘When you were young, I really thought it was a phase… The form does not fit the content.’

He waits at Asphodel’s gates for his mother with Fotis, a puppy-like Cerberus, a playful nod to Heracles’ famed twelfth task. Caeneus and Riddy fall in love, but Orpheus, still obsessed, arrives in the Underworld. Riddy chooses to leave with him but breaks from the classical myth by bidding him goodbye upon returning to Earth, forging her own path. Caeneus remains in Apsphodel to change the fate of trapped souls, and in a Casablanca-like farewell, they kiss, promising they’ll always have Paris, oops Hades.

The state stooge President Minos, originally King of Crete and son of Zeus and Europa, rules Krete, obsessed with achieving immortality.

The state stooge President Minos, originally King of Crete and son of Zeus and Europa, rules Krete, obsessed with achieving immortality. His daughter, Ariadne, is our third hero, and her story gets a powerful flip. In classical myth, Ariadne helps Theseus escape after he kills the Minotaur, only to be abandoned on the shores of Naxos. In Kaos, Ari does like Theseus, but she controls the narrative this time.

The shores of Naxos become Nax, son of Andromache and grandson of Hecuba. Timelines are juggled, with Nax as a rebel who desecrated Zeus’ monument. Hecuba and Andromache, classically royal widows, are now leaders of the rebel Trojan community—refugees oppressed and culled by Krete.

Theseus, in love with Nax, seeks Ari’s help to ask Minos for a pardon for captured rebels. Tragedy ensues after Ari ends up realising the crimes her father committed against her twin Glaucus for thirty years, due to a prophecy. Interestingly, it’s always the men—Minos, Zeus—who are haunted by prophecies, while female characters seem largely unconcerned. Fulfilling the prophec, Ari is set to rule Krete.

The queer fate of Kaos

Near the season’s end, Zeus reveals his full villainy as the three main characters uncover the truth about the Gods and the prophecy that could topple the empire. The stories that will bring the downfall are reimagined through a queer-feminist lens. Two other sets of characters hold power beyond the Gods: the Fates and the Furies.

The Fates—Clotho, Atropos, and Lachesis—appear at a bar called the Cave, run by Polyphemus, which has a portal to Hades. Played by Sam Buttery, Suzy Izzard, and Ché, these trans-non-binary divine beings control not only human destinies but also the Olympians’. In a misguided Macbeth-like move, Zeus tries to destroy the Fates to prevent his prophecy, but they laugh as Prometheus is unbound despite their “destruction.” Buttery, in an interview, remarked, ‘Existing and operating as a trans person, you can often feel quite immobilized or powerless because I suppose the fate – pardon the pun – of your life is discussed in an abstract setting, like the government.’

Buttery, in an interview, remarked, ‘Existing and operating as a trans person, you can often feel quite immobilized or powerless because I suppose the fate – pardon the pun – of your life is discussed in an abstract setting, like the government.’

The Furies—Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone—make a brief yet striking appearance. Riding motorbikes in leather jackets, they present as brusque, masculine-presenting gender-ambiguous figures, possibly a nod to the 1970s lesbian separatist Furies Collective. Despite their tough demeanor, they are caring, with Tisi even sewing footie pajamas for Ari before revealing the truth about her twin brother.

Flipping the narrative, changing the voice

Homeric women were largely subjugated, victims of a deeply misogynistic ideology, much like how Zeus treats women in Kaos—always suspicious of them. Classically, Hera is depicted as vengeful and jealous, but in Kaos, she is equal to Zeus in taking lovers and power. In Classical Greece, the oppression of women was intended to prevent them from causing chaos. In Kaos, the women are happily starting fires everywhere.

Rape in Greek mythology is nearly synonymous with heterosexual relationships. Persephone was famously kidnapped by Hades and forced into marriage. In Kaos, however, she loves Hades and wants to bring Zeus down to avenge her husband’s suffering. She even blames Hera for spreading rumors about their relationship and quips that she’s allergic to pomegranates—the fruit that allegedly bound her to the Underworld.

Meanwhile, Medusa, in full corporate-girl mode, takes charge of sending Eurydice back to Earth to ruin Poseidon’s family (the reason she has snakes for hair). Cassandra almost spoils the whole season in the first episode, but as always, her prophecies are ignored—until it’s too late.

The queer redressal of the canon is Kaos‘s most powerful aspect. Prometheus is in love with Charon, the ferryman, but betrays him to fulfill the prophecy, sending him to Hades. Watching two white-haired men passionately in love is a rarity in popular media. Caeneus, played by a trans man – Misia Butler, and the Fates, portrayed by trans and non-binary actors, bring authenticity to this reimagining.

Not to mention the show’s creator Covell identifies as non-binary. The two directors of the show – Georgi Banks-Davies and Runyararo Mapfumo, have been known to work with queer and feminist materials. With so many forces together, the queer lensing did not feel forced or half-baked. Dionysus has casual sex with a man in a bathroom, and Hera takes Zeus’ form to sleep with one of his lovers—queer themes are woven through the lives of the Olympians.

But Kaos doesn’t shy away from the violence either, though it often feels more horrifying than humorous.

But Kaos doesn’t shy away from the violence either, though it often feels more horrifying than humorous. From Zeus wringing a baby’s neck to Dionysus sealing a saleswoman’s mouth, the brutality is unsettling. Zeus killing Dennis the cat or his ball-boys pushes the boundaries of discomfort. One can’t help but hope for a second season, just to see Zeus fall from his pedestal. Hera’s final march, flanked by her Tacitas, after calling her child (possibly Ares?) feels very House of Cards—and we are here for it.

One article can’t capture the many lenses through which Kaos can be viewed. It critiques the Global North vs. Global South while also mocking capitalist consumption — over-accumulation of capital will lead the system to collapse, like the Nothing problem. Minos and the Trojans evoke Israel’s treatment of Palestine. It’s hard not to laugh when Prometheus quips, ‘The gods thrive on one thing, distraction.’ Beyond the contemporary parallels, mythology lovers will delight in the detailed references, making it perfect for rewatching. Kaos repeatedly underscores the power of storytelling, proving that queer voices telling queer stories will always, always be powerful.

About the author(s)

She/they is an editor and illustrator from the suburbs of Bengal. A student of literature and cinema, Sohini primarily looks at the world through the political lens of gender. They uprooted herself from their hometown to work for a livelihood, but has always returned to her roots for their most honest and intimate expressions. She finds it difficult to locate themself in the heteronormative matrix and self-admittedly continues to hang in limbo