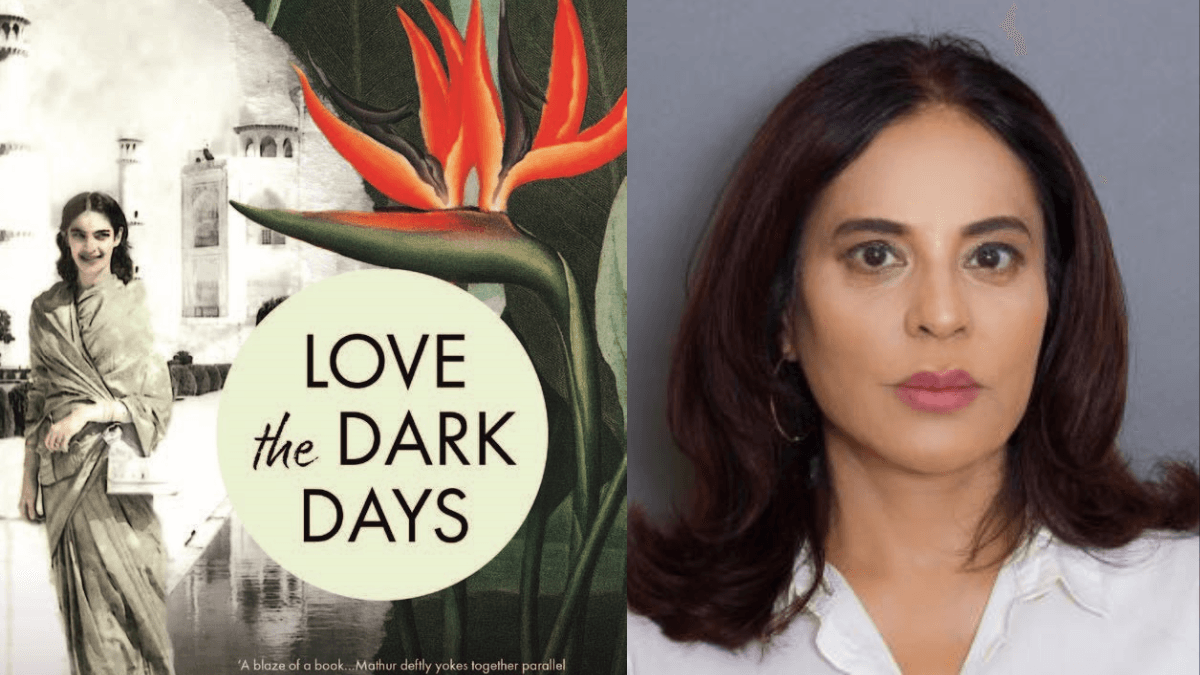

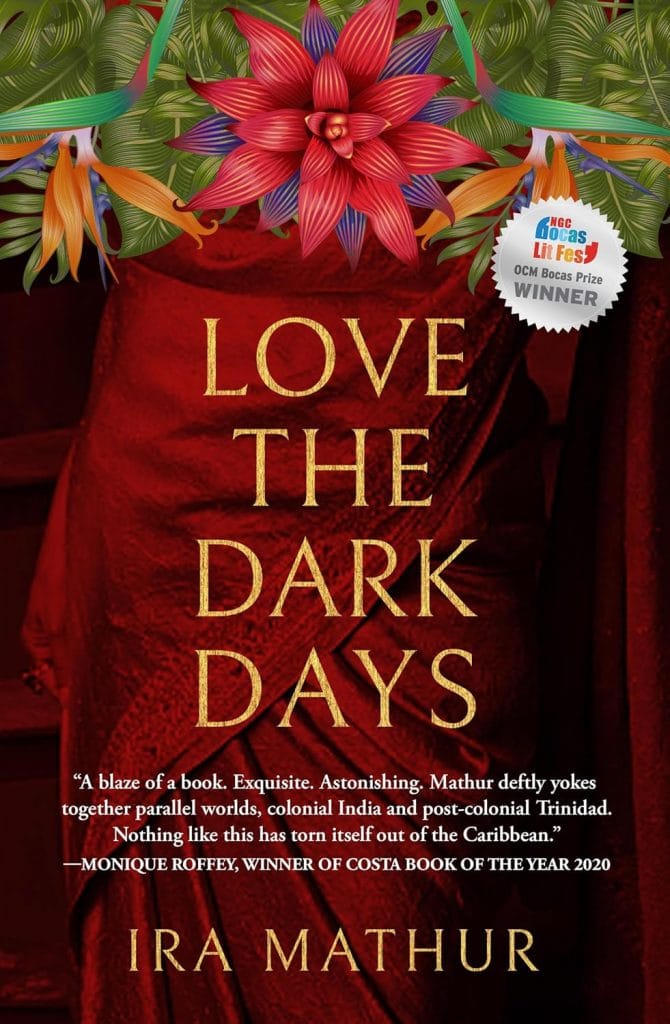

Love the Dark Days is Indian-born Caribbean author Ira Mathur’s memoir, published by Speaking Tiger in India. The title, borrowed from a Derek Walcott poem, is a tribute to the author’s close association with the Caribbean Nobel Laureate, who appears in the text as a mentor and guide. Mathur intricately weaves together her turbulent family history and personal life with the time she spent at St Lucia under the mentorship of Walcott, in parallel storylines. Love the Dark Days is deeply personal and rooted in the author’s abject sense of unbelonging throughout her life.

The memoir starts where mostly all memoirs start- during the author’s childhood. Descended from the royal families of Savanur and Bhopal on the maternal side, the author is born to a Muslim mother and a Hindu father, which becomes a recurrent point of contention within the family. The daughter of an army officer, the author spends a good part of her childhood with her regal and stately grandmother, Burrimummy, in a house in Bangalore.

Here, the author experiences a sense of unbelonging, as her younger sister Angel receives a lot more affection from their grandmother. As the author is taken to Trinidad by her parents during adolescence, the sense of unbelonging heightens, exacerbated by a sense of rootlessness in a foreign land. Mathur describes going to boarding school in London followed by University and how she ultimately comes back to Trinidad to work as a news journalist.

Navigating her away through a marriage which seems tenuous at times, family responsibilities and social expectations, Mathur tries to process her life by writing about it. The poet Derek Walcott who reads her manuscript, tells her it is rooted in a past, and asks her to write about her present and move away from the vestiges of Indian royalty that Burrimummy treasured. The author’s memoir, therefore, becomes her journey to self-realisation, to finally seeking help for her unresolved trauma and making amends to move forward.

The relics of royalty

Burrimummy and the author’s mother are descendants of the royal family of Savanur in India. Burrimummy was married to royalty in Bhopal, however, after her husband’s string of illicit affairs, she leaves the marriage with her young daughter, denouncing all her royal privileges from her in-laws. The author’s Burrimummy exists in a bubble of the past when royalty in India was treated with utmost respect and reverence. Even in Bangalore, where her royal background can only fetch her social currency and nothing else, Burrimummy behaves like a queen, ordering the help and the staff and treating them like slaves.

Burrimummy lives in the past, pulling down photographs of her royal ancestors to regale their stories to her grandchildren. She is partial, giving much of her affection to Angel, because she looks like her. Burrimummy’s disapproval of her daughter marrying the author’s father, a Hindu, leads her to take away her daughter’s inheritance, paving the way for a long-drawn legal battle. The tense relationship between the author’s grandmother and mother reflects in the author’s relationship with her mother which is burdened with the legacy of generational trauma.

In Trinidad, Burrimummy tries to use stories of her royal lineage to her advantage just like she had always done in India. However, the Trinidadian-Indians who were mostly indentured labourers during the Raj, view her with contempt as does Derek Walcott, when Mathur talks of her royal lineage.

The text, therefore, becomes a testament to the breaking down of the very concept of royalty in modern India and the New World. Stuck in a glorious past, it is difficult for Burrimummy to accept that. In one instance from the text, Burrimummy is taken to the Trinidadian carnival by the author and her husband Sadiq, when she hears of a ‘king,’ at the festival. A surprised Burrimummy asks Sadiq if there is royalty on the island. When Sadiq explains to her the carnivalesque concept of how anyone in the festival can be crowned ‘king’, Burrimummy is taken aback.

Trauma and memory in Love the Dark Days

The author retraces memory and attempts to resolve her trauma through the act of writing. Taking from an entire lineage of maternal ancestors, the author is blessed with generational trauma aplenty. Burrimummy and her mother, whom we hear being called Mumma, do not see eye to eye after the former leaves her first husband to be with an abusive Pakistani officer. Burrimummy and the author’s mother gave their contentions owing to the latter having an interfaith marriage. Finally, the author, in her childhood, is an exact foil to her mother and grandmother, owing to her dark skin and her features. She is doubly ostracised, by a partial grandmother who favours her sister and a neglectful mother who only visits her as per her convenience and barely makes the author feel loved.

However, as the narrative progresses and the author enters adulthood, we see her trying to resolve the familial conflict with her mother and grandmother. When Burrimummy is taken from the house in Bangalore to the author’s home in Trinidad, we see the once formidable Burrimummy has become weak, aged and unable to take care of herself. Mellowed by age and illness, she and her granddaughter try to reconnect. However, there are major obstacles in their relationship, as Burrimummy’s attitude towards her caregivers and her stubborn persistence hamper their relationship so much that the author is compelled to send her grandmother to a nursing home for the aged in Trinidad.

Multiculturalism and the author’s identity in Love the Dark Days

The author is born of interfaith parentage and in her adolescence, moves to the Caribbean, a melting pot of diverse cultures. The author and her family have a hard time negotiating with their identity and social position in a setting as diverse as Trinidad. Burrimummy is confronted with the fact that her royalty meant everything in India and nothing here, and is unable to accept this fact. The author cannot relate to the culture of her husband and his family, who are descendants of indentured labourers from India. This forms a major point of conflict in their marriage wherein the author feels like she doesn’t belong with her in-laws.

However, neither does she belong to the elite royalty of Bhopal anymore. After her grandmother denounced her royal in-laws, the author, her siblings and her mother travel back for a wedding, decades later, to the royal family in Bhopal. Disinherited and cut off from their privileges, they are not allowed to view the bridal jewels and are not fully accepted by that arm of the family. It is only with the old servants who remember the author’s grandparents that they find true acceptance.

As the author travels from India to Europe, to the Caribbean, she realises she doesn’t belong anywhere fully. She carries within her the very multiculturalism that she has lived through, making her a part of everything and nothing at once. Derek Walcott writes in “The Schooner Flight“: Either I’m nobody or a nation. The author similarly, embodies all the multiculturalism of India and the Carribeans and the memoir is a tale of how all internal conflict culminates into self acceptance, as Walcott writes:

“Take down the love letters from the bookshelf, the photographs, the desperate notes,

peel your own image from the mirror.

Sit. Feast on your life.“

About the author(s)

Ananya Ray has completed her Masters in English from Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India. A published poet, intersectional activist and academic author, she has a keen interest in gender, politics and Postcolonialism.