Discrete and overlapping patriarchal arrangements enforce a hegemony that has dictated the lives of women for centuries. Women’s life narratives are an intervention in this discourse providing us with an epistemological standpoint with a more encompassing vantage point of the society. In articulating their individual “self” women’s autobiographies also give a contrapuntal reading of the patriarchal heteronormative society.

However, these life narratives are polyphonic and cannot be homogenised in the context of postcoloniality, caste hierarchy and cultural differences of the writer. Different social locations demand different readings of the text.

The ideological refreezing of man’s position within the socio-political matrix of the 18th century was most decisively acted out on the world stage in the form of two revolutions- The American Revolution (1765-83) and The French Revolution (1789-90). These revolutions produced two significant documents, the United States Declaration of Independence (1776) and the Declaration of Rights of Man and the Citizen (1789). Both of these documents undermined the earlier belief in a divinely ordained hierarchical society. They established a new idea of man’s place in society based on the principles of rationality.

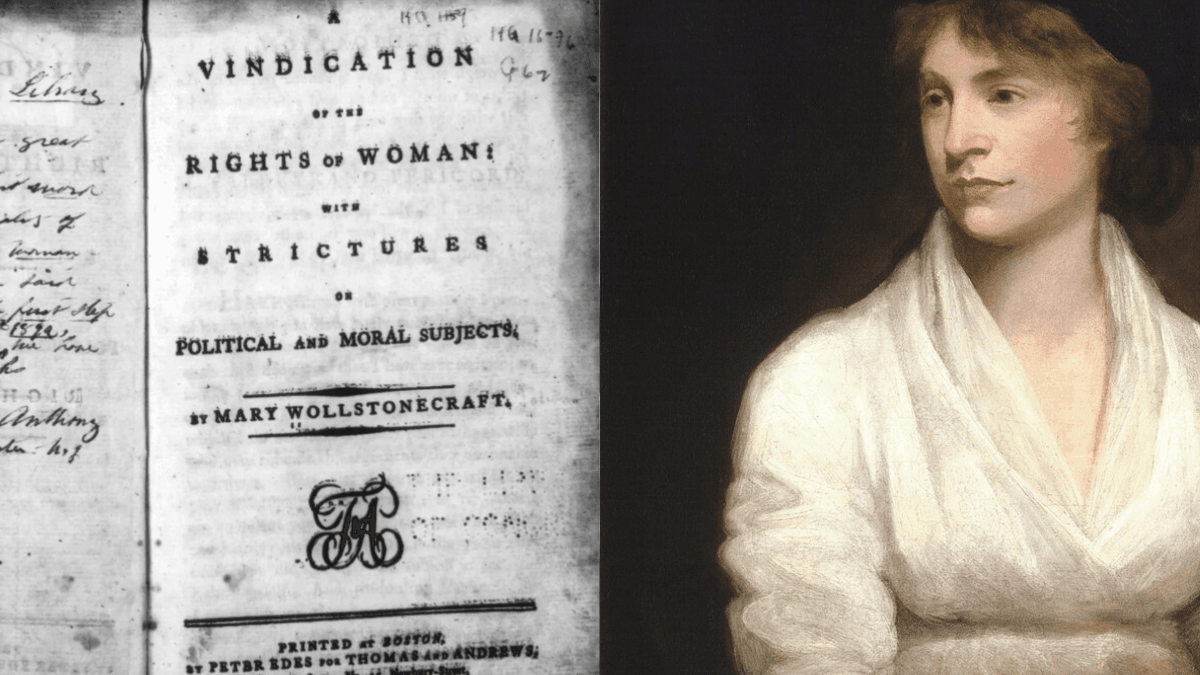

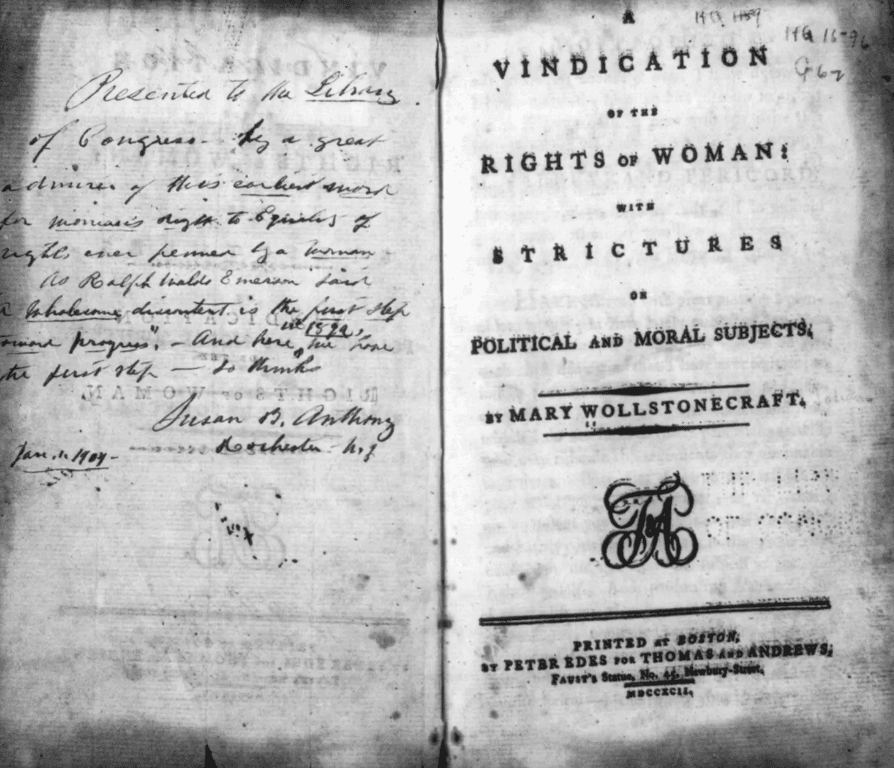

Mary Wollstonecraft in her treatise On the Vindication of Woman’s Rights tries to intervene in this changed scenario politically. She tries to place women on the same platform of rationality that the contemporary discourse of human rights and political citizenship was placing men on. Wollstonecraft asserts that women by being humans are as rational as men. And, therefore, as much a claimant to natural rights as men. If this status as rational subjects are at all denied or questioned, then they are denied by men, who do so without consulting the women. This in itself is a sign not only of injustice but also of “tyrannical irrationality.”

“Who made man the exclusive judge of that if woman shares with him the gift of reason?“

Wollstonecraft does away with the question, of whether women are rational or not. She claims the discourse by asking the question who says women are irrational? She goes on to state that any statement regarding women’s irrationality is itself made from a position that is inconsistent, unjust and not rational enough. She, however, argues that most women do appear to be ignorant, lazy and irresponsible within society, but she argues that this is not, because of any inherent lack of rationality in them, rather it is because they are denied proper education by their fathers and because any exercise of their reasoning faculty is looked down upon by society at large, which regards such exercise of the reasoning faculty as “unfeminine“.

Lawrence Stone in his monumental study The Family, Sex and Marriage commented on the 18th century “conservative corpus” of manners which was fashioned for women to safeguard domesticity and the private sphere. The central criticism of this foundation Anglo-American feminist treatise is evident in its commentary on Jean Jacques Rousseau’s Emile, which asserts-

“One should be active and strong, the other passive and weak.”

“It is requisite of her to be modest, circumspect and reserved; and that she should bear in the sight of others, as well as in her own conscience, the testimony of her virtue.”

Wollstonecraft is highly skeptical of having a female education which limits its doctrines to teaching women the maneuvering of their physical charms to entice men. She asserts active engagement of women in all domains instead of passive domesticity. Her aim is to culminate “more observant daughters, more affectionate sisters, more faithful wives, more reasonable mothers.” Her suggestion is therefore to completely overhaul the education system for women which would allow them to emerge as fully rational beings, who are at par with men. But she is also aware that it requires more than the change of heart of individual patriarchs within the family about the education of their daughters to establish women as rational beings. This is because, she argues that both men and women were ultimately “educated to a great degree, by the opinions and manners of the society.”

The notion of femininity, she finds it too deeply rooted within the patriarchal society to allow women to emerge in the socio-political arena as rational citizens. She therefore advocates that society itself should be radically transformed to “bring about a revolution in female manners.” The indoctrination of the patriarchal discourse is such that from an early age the female child is conditioned to follow the masculine assumption of femininity.

The text describes this as “barren blooming” which is attributed to a “false system of education” imposed by narratives written by men to create more “alluring mistresses than affectionate wives and rational mothers.” In other words, she detested the infantilisation of women in male texts. However, a contrapuntal reading of the text reveals how Wollstonecraft herself has internalised many of the prejudices of the dominant narrative of patriarchy. Mary Poovey opines, “Wollstonecraft’s distrust of women’s sexuality (including her own) is evident.”

Though the text radically revises the conception of female education, political engagement and claim to intellectual debate, its beneficiaries are limited to middle-class docile wives and conventional motherhood. Cora Kaplan in her essay “Wild Nights: Pleasure/Sexuality/Feminism” asserts that in her critique of Rousseau’s treatise Wollstonecraft has appropriated many of the concerns of the former relating to the debate of passion (baser and associated with women) and reason (intellectual and associated with the masculine).

Kalpan writes, “She accepts Rousseau’s ascription of female inferiority and locates it even more firmly that he does in an excess of sensibility.” Wollstonecraft does away with the female right to sexuality and pleasure to anchor the discourse of “rational” women. Moreover, this ideation is limited to bourgeois middle-class women. The working-class women, as Kalpan puts it, “worked too hard at severe manual labor” to have been concerned about “a passion for clothes,” or mercantile superficiality. Like Rashsundari Debi’s autobiographical account Amar Jiban this treatise too has a duality or rather a paradox.

On the one hand, she is dissenting male texts like Emile and Bruke’s’ classist and sexist sentiments, “on the other hand “her manner of rationalizing the claim of equal rights across sexes are strikingly similar to the male conservative voice of the abstract enlightenment rationalist.”

Nevertheless, Wollstonecraft’s construction of a category of new women compounded the intersection of moral reform, class tension and gender consciousness. Both transgression and subversion are evident in her text establishing it as the foremost document of Anglo-American feminist criticism.

However, it needs to be highlighted that these texts emerge from socially privileged locations on accounts of cultural capital and class. Wollstonecraft’s distrust of the “feminine” was invisible to the section of working women in Industrial England. However, as proto-feminist and early-feminist texts these writings laid the blueprint of the anticipated feminist waves. It established a tradition of questioning the centre and dissent that not only created the category of “the new woman” but also introduced the possibility of dissent and revision within the feminist worldview.

References:

- Stone, Lawrence. The Family, Sex and Marriage in England 1500-1800. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1977.

- Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. 1792.

About the author(s)

Anchal is a writer, poet and spoken word artist based in New Delhi. Her works have been published on various platforms, including Enroute Indian History Blogs, Indian Review E-Journal and department and annual magazines of Miranda House, Kirori Mal College and Gargi College. Currently, she is pursuing an MA in English at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and loitering around the city.