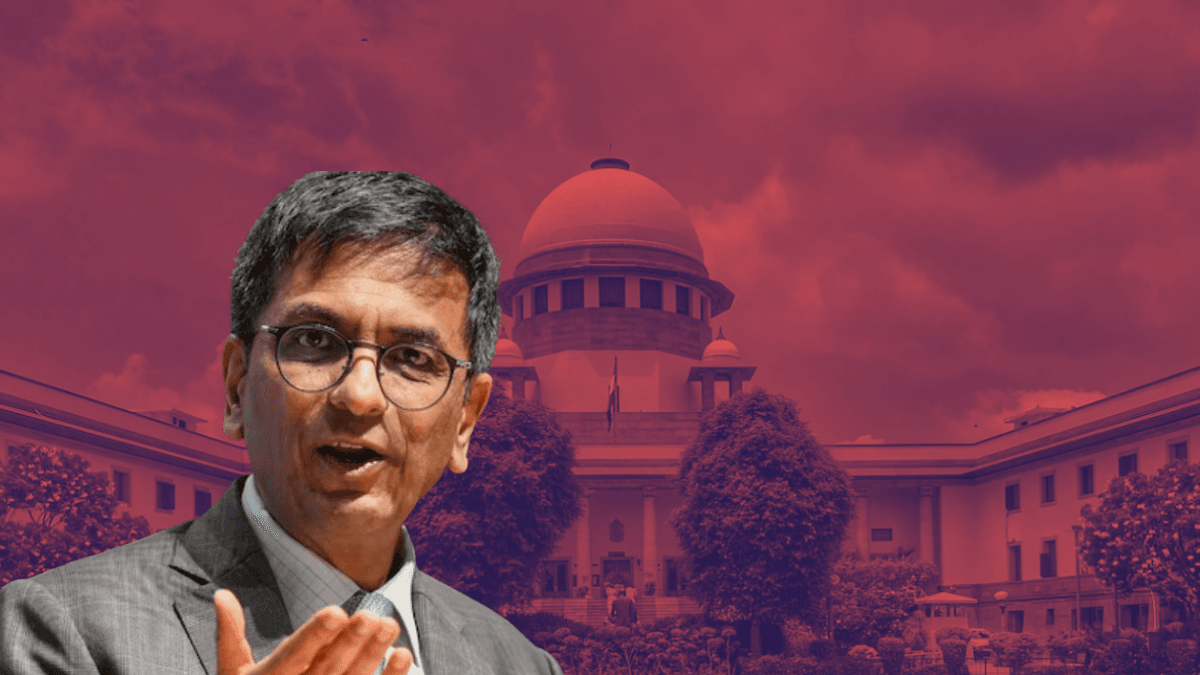

On 10th November, Chief Justice of India, Dhananjaya Yeshwant Chandrachud, is all set to retire from his office. As the 50th CJI of India, he served for two years at India’s topmost judicial body. Justice DY Chandrachud, who took up the role of CJI on November 9, 2022, following the retirement of former CJI UU Lalit has had the longest term for any CJI in the last 14 years. With this short span, not so short in the judicial realm, one cannot recall Chandrachud’s judicial journey without discussing the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid Case or even the abrogation of Article 370 or many other judgements like on Maharashtra’s political crisis or Delhi’s bureaucratic power struggle between the AAP-ruled government and the BJP at the centre.

Chandrachud has even been a part of a bench that dismissed calls for an investigation into the mysterious death of Judge BH Loya, a murder case hearing involving Home Minister, Amit Shah. In a country where “bench-fixation” (politically motivated judicial appointments) have been accused of, Chandrachud’s tenure was both controversial and historic.

1. Babri Masjid dispute: Chandrachud’s deity-driven judgement

In 2019, after the Modi government secured a second term with a stronger mandate, Chandrachud became a part of a bench that delivered a judgement that effectively served as a gift to the ruling party’s political agenda of Hindutva Nationalism, the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid Dispute case. The case needs no introduction. At least post the 22nd January’s grand consecration ceremony on the then-disputed site where Babri was demolished by Hindutva mobs in 1992.

In a felicitation ceremony quite recently, CJI Chandrachud shared, “I sat before the deity and told him he needs to find a solution,” for the Ayodhya Dispute Case. Publicly admitting to his indecisiveness and dilemma in the case. One may wonder whether most of his judgements were based on such a dilemma. Is this how courts decide and declare judgements in India?

Deities should not decide a solution meant for the judiciary to make, especially when it involves one. However, Chandrachud’s role in the deity-driven solution he revealed he made as a part of the bench that gave the Ramjanmabhoomi-Babri Masjid Dispute verdict allowed the construction of the Ram temple on the site where the Babri Mosque was demolished illegally. Bringing a politically motivated and favoured resolution to a decades-long dispute in the country. Making one question whether the judgement was a deity-driven solution or succumbed to political pressure from the ruling government or perhaps a political agenda.

2. Abrogation of Article 370

Next is the case of challenging the abrogation of Article 370 by the BJP government. On 11 December 2023, five senior-most judges of the Supreme Court headed by CJI Chandrachud upheld the constitutional validity of the government to abrogate Article 370. The one that granted special status to Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). The Court refused to comment on the constitutionality of the reorganisation of J&K state into two Union Territories: Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, and also the special privileges granted that were now denuded.

Thus, conveniently blindfolding Lady Justice’s eyes again towards Kashmir by reducing the arguments on the case on grounds of the section being a ‘temporary provision,’ of the Constitution. Justice Chandrachud allegedly simply followed the government line yet another ruling.

3. CAA-NRC

The Supreme Court, in a bench led by Chandrachud with a 4:1 majority verdict on October 17, 2024, upheld the constitutionality of Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955. The provision grants citizenship to immigrants who entered Assam between January 1, 1966, and March 25, 1971. The section serves basis for the National Register of Citizens after getting a green signal from the Union government. This provision was challenged in court, with petitioners arguing that it violated the Constitution by allowing a different cut-off date for citizenship in Assam compared to the rest of India.

However, the CJI Chandrachud-led bench upheld the CAA. A law that sparked massive protests in the country, especially in 2019-20. As a result of which, many political activists are still under prolonged imprisonment without trial. A law that seems highly discriminatory and ostracises a particular section of minorities.

4. Extension of abortion rights under the MTP Act

The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act limited abortion access primarily to married women or in specific circumstances to unmarried women, reflecting outdated patriarchal norms. A petition was filed challenging these restrictions.

On September 29, 2021, Justice Chandrachud led the bench to examine whether such limitations were discriminatory against unmarried women. The ruling that came on International Abortion Rights Day extended abortion rights under the MTP Act to unmarried women as well. It removed several unnecessary restrictions on abortion. Thus, the judgement re-enforced women’s autonomy in matters of abortion. Laws around abortion in India are therefore now much more progressive than in the US. However, note that this was a judgement before Chandrachud became the CJI.

5. Ministry of Defence vs. Babita Punia case

In a two-judge bench, with CJI Chandrachud being one, the Ministry of Defence v. Babita Poonia (2020) case upheld a judgement affirming gender equality in the Indian Army. The court directed the Indian Army to grant women officers permanent commissions, which were earlier limited to men. Rejecting arguments based on stereotypes reinforced by previous rulings. It recognised the contributions of women officers and upheld their right to equality of opportunity. It ordered all eligible Short Service Commissions (SSC) to consider women officers for permanent commissions. Thus, marking a significant step towards gender inclusivity and equality of opportunity in career progression within the armed forces in the country. Another milestone was achieved in judicial history in terms of gender justice.

6. Decriminalisation of homosexuality

On September 6, 2018, a five-judge bench of which Chandrachud was a member had partially struck down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). Thus, achieving a milestone in the history of Supreme Court judgements by decriminalising same-sex relationships between consenting adults.

In a country where same-sex couples are highly ostracised, Chandrachud felt the law reduced a section of citizens to the margins. Calling the section “anachronistic colonial law,” his role in the bench specifically encouraged the argument of having faulty categorisations of human sexuality members in mere binary terms of male/female.

Observed as one of the first steps towards a path of guaranteeing LGBTQIA+ individuals their constitutional rights. However, the law still fails to address the question of same-sex marriages. The next important judgement is in this regard.

7. Marriage equality verdict

In a verdict last year in the Supriyo Chakraborty & Anr. v. Union of India Case, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court comprising Justice Chandrachud declared how the right to marry wasn’t fundamentally granted by the Constitution. Yet again shutting doors for same-sex couples to legalise their relationships in the form of matrimony in India.

However, Chandrachud in that judgement considered the right for queer couples to enter into ‘civil union,’ under Article 19, which guarantees the right to freedom of forming associations. But his opinion didn’t really materialise into a verdict, and marriage equality is still not granted to queer couples.

For the most part, Chandrachud successfully maintained an image of a judge who challenged the executives, but mostly in cases related to personal liberty, the right to privacy, free speech, gender, and queer rights. Some of which have been mentioned earlier. Others, for instance, cases like the Sabarimala Temple verdict, where a bench including Chandrachud allowed women of menstruating ages as well to enter the temple, which once restricted their entry in the name of a celibate deity, or the decriminalisation of adultery on grounds of personal autonomy and privacy.

However, once he became CJI, Chandrachud’s conduct as head of the topmost judicial body in the country on several political matters seemed unclear as compared to when he was not the CJI. This makes one wonder whether one of the longest-serving Chief Justices was somewhat subjugated to political pressure in his tenure. Even earlier this week, Chandrachud commented on how the independence of the judiciary does not imply always delivering verdicts against the government. Is he trying to indirectly indicate something? Perhaps the judiciary’s autonomy as an independent body is in danger. Again, this makes us question whether the judiciary is just a puppet of the executive. As he retires this week, all eyes are set on his successor, Justice Sanjiv Khanna, who will lead the country’s topmost judicial body for the next six months.

References:-

- https://caravanmagazine.in/law/equivocations-of-chandrachud

- https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/sc-upholds-abrogation-of-article-370-says-move-was-part-of-70-year-old-exercise-to-integrate-jk-to-the-union/article6762

- https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/abrogation-of-article-370-an-analysis-of-the-supreme-court-verdict/

- https://www.scobserver.in/reports/citizenship-amendment-act-supreme-court-refuses-to-stay-the-caa-rules-directs-union-to-file-responses-to-interim-stay-applications/

- https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/assam-accord-hearing-live-sc-verdict-on-pleas-challenging-section-6a-of-citizenship-act/article68763241.ece

About the author(s)

As an independent journalist, writer, and aspiring documentary filmmaker, Stuti covers about social and political issues. Interested in development journalism she also highlights issues on human rights, gender, education, unemployment, law and others. She aims to start her own news media initiative in the future to transform the way development is covered and discussed in the news.