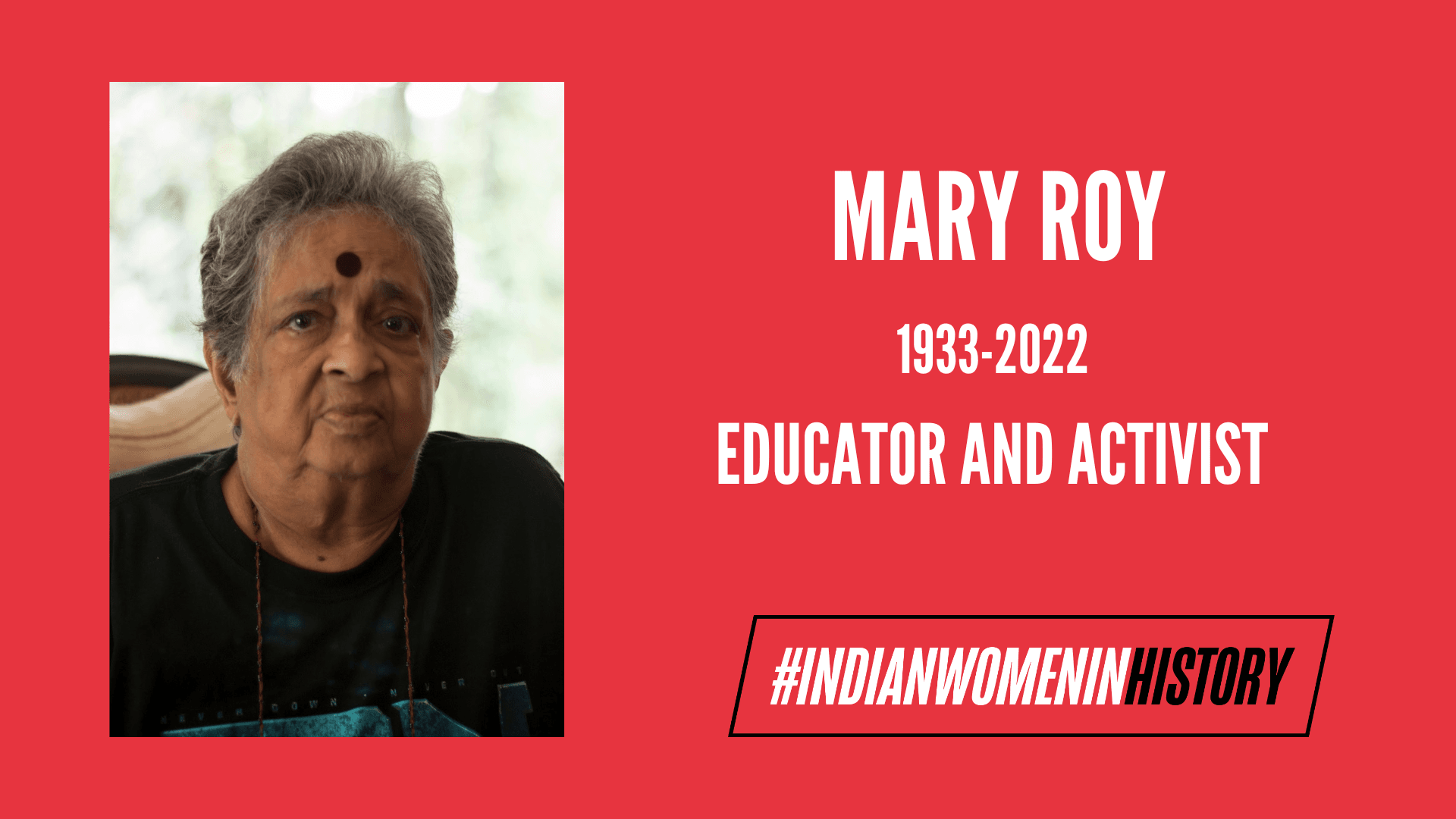

Mary Roy succeeded in securing for herself and the women of her community the rightful claim to equal share in the family property. Mary Roy Vs. State of Kerala, adjudicated by Justice R.S. Pathak and Justice P.N. Bhagwati proved to be a major challenge to the Syrian Christian norm. This battle, aimed at procuring an equal share of her father’s property, culminated in the historic ruling of the Apex Court against the patriarchal Travancore Christian Succession Act (1916).

The Act mentioned the line of descent passing from father to son, with no mention of the daughter except the provision of one-fourth of the share in the property or ₹5000 to be inherited by her, whichever amount was lesser.

In 1983, Roy filed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) against the Act which was ultimately abolished in 1986. However, it was only in 2010 that Roy, her sister and her widowed sister-in-law procured a share of property due to them.

The ‘D’ word: Deviance or dowry?

Inheritance as a means of accessing property is available to both men and women. However, in Indian society, marked by deep-seated patriarchy, there is a structural dichotomy between access to property for men and women. Roy grasped the link between customs enmeshed in patriarchy and how they suppressed women, perceiving the Act as a double burden for unmarried women, widows and divorcees. Roy was introduced to the Act only after her father passed away without drafting a will and subsequently, her brother denied her any share in the family assets.

The Act applied to all the residents of Travancore and was adhered to by her family, her mother is a case in point, bringing an exorbitant amount of dowry upon her marriage. It was ironic that the Travancore Christian Succession Act of 1911 coexisted with the Dowry Prevention Act of 1961! The district collector of Kottayam perceived Roy’s legal battle as an act of deviance as he argued, “In Kerala, the social fabric has survived without much damage because people have traditionally learnt to respect other religions and have learnt to coexist. Here, in this case, the danger comes from an individual’s, the principal’s, idiosyncrasies. When she elevates her contempt for humanity and wells it to the public in a so-called art form, the believers will be on a warpath. When the sacred premises of a school is converted into an area for the perpetuation of hatred in innocent minds it crosses the limits of acceptable private idiosyncrasies.”

Streedhanam was a central component of marital ties within the Syrian Christian community. This was illustrated by the fact that along with the petition filed by Roy, one of the attachments was an excerpt from Manorama, a Malayalam weekly, featuring the matrimonial page highlighting the share of women specified in each matrimonial ad, avoiding the use of the word ‘dowry.’

The rationale behind the custom of streedhanam is that the father’s property, particularly land, goes to the son or male heir as part of the patrilineal system of inheritance. The practice may be understood as an equivalent of dowry or the only wealth that a daughter receives from her family upon marriage, which is merely a fraction of the share of parental property that a son receives. It could also be understood as a means of catering to the material or monetary interests of the groom’s family, reducing the woman to the status of a mere object or “property” to be exchanged.

An individual and collective struggle

When the TCSA was used as a weapon against her by her brother, her reaction was one of disbelief, disappointment and refusal to conform, “can you imagine the value of a female is fixed at a quarter of that of a male?” she said. “And her maximum worth is ₹5,000! What greater blow can there be to human dignity?” It was a personal, legal, and political battle against her brother, George Isaac’s claim to the entire share of their father’s property.

In its ruling, the Supreme Court did not base its decision upon the violation of equality as enshrined in Article 14 of the Indian Constitution. On the contrary, they argued that the Travancore Christian Succession Act could not exist after the Part B States (Laws) Act was passed in 1951 which made the Indian Succession Act operational in Travancore. Travancore-Cochin was also a Part B state.

According to the provisions of the Indian Succession Act (1925) property “shall be equally divided among all surviving children if an individual dies intestate, without a Will.” However, this led to families preparing the Will in advance to ensure that the family’s assets were only transferred to the sons. Dowry is a practice deeply entrenched within the fabric of Indian society. While the Indian Succession Act brought all Christians under its ambit, it is still contended that dowry is in practice a woman’s share in the family property.

What immediately followed the verdict was Roy filing a case in the Kottayam District Court demanding a fair share in her father’s estate property, which resulted in the case being dissolved. The court held that the property couldn’t be distributed before the death of her mother. Her siblings further argued that having obtained the cottage in Ooty, she was not in a position to express more demands. Roy believed that women had been “brainwashed by the men” and that if they dared to assert the demand for an equal share in the property, they would threaten the very foundation of the Syrian Christians. In her struggle against the implicit custom of dowry, she was joined by a teacher, Mariakutty and a nurse named Elikutty, who themselves were “given away” in marriage as part of the practice.

Parallels between Arundhati Roy’s Ammu and Mary Roy

The character named Ammu in The God of Small Things authored by Mary’s daughter Arundhati Roy is an ode to Mary Roy’s unwavering resilience and non-conformity. Although Ammu’s character was defiant and courageous just like Mary Roy’s, there’s one thing that the latter exclusively had- her painstaking, prolonged battle with the gender unjust norms of society.

Like Ammu, she was a rebel, who refused to submit to an archaic practice rooted in patriarchy and resisted her worth being reduced to ₹5000. However, it wasn’t a fight for monetary gain, but equity, the essence of which is captured in her words, “I don’t need it, but I want to show the world that I can get what I want.”

Flipping through the pages of the novel, one is compelled to read the lines which testify to the rebel in both Ammu and Roy, “She developed a lofty sense of injustice and the mulish, reckless streak that develops in Someone Small who has been bullied all their lives by Someone Big.” Like Ammu, Roy is defiant and gutsy and not bothered by the tag of a “wretched manless woman“. A paragraph referring to Ammu in the novel accurately describes Mary Roy, “Ammu had not had the kind of education, nor read the sort of books, nor met the sort of people; that might have influenced her to think the way she did.”

While Ammu harbours the dream of running a school one day, Roy translates that dream into actuality, by establishing the Corpus Christi High School in Kottayam.

A staunch educationist

Roy laid the foundation of Pallikoodam in 1967 which ultimately became the Corpus Christi High School, where learning wasn’t confined to merely textbooks. Roy would bathe the children, teach them and put them to sleep. In the absence of textbooks, experience was the foundation of growth.

Roy was an ardent believer in reform through education. She set into practice the use of Malayalam for all practical purposes in school up till grade 3, for establishing the children’s connection with their mother tongue in the formative years.

Among her students, she emphasised questioning the why of everything, challenging retrogressive norms and conventions and expressing dissent through protests.

Mary Roy: Rebel or resilient?

In an interview with Mathew John in 2006, Roy stated, “What happened to me will not happen to anyone ever again. The ones who came after me did not have to go to the courts to claim their share., I was just angry. I was doing it for the public good.“

Referring to her battle with her brother for succession rights, she stated, “We clashed on a matter of principles.” For Roy, it was not about the 4000 sqft. of property she received, but the ideal of equality.

Her battle is hailed as a landmark case in the history of gender just judgements and the Indian law by both, the public and the church. However, what Mary Roy perhaps will be remembered for is not only this victory but also the path she undertook. She leaves behind a legacy of unstaggering grit to articulate and assert one’s rights. Her victory in 1986 was not a personal one, it was a collective victory of the Syrian Christian women tied down to the norms of their community.

About the author(s)

Syeda Shua Zaidi is a student of B.A. (Hons) Sociology, at Miranda House. Passionate about poetry, filmmaking, heritage walks, social work and all things vintage, you would find her reading the works of Murakami, Khaled Hosseini and Agatha Christie while treating herself to a cup of tea. Firmly a believer of "disagreements are welcome, disrespect is not".