‘Wait for me if this is real. I don’t want you to wait as Penelope did, I don’t want you to be deprived. Seek out, taste, enjoy every pleasure. I want you to choose me not from paucity but after you have made other choices, walked through other fires. I don’t want to grab your hand. I want you to put it in mine. Drink me, consume me, never let me out of your sight, give me ground on which to stand with you, face to face.‘

–A Slight Angle, Ruth Vanita.

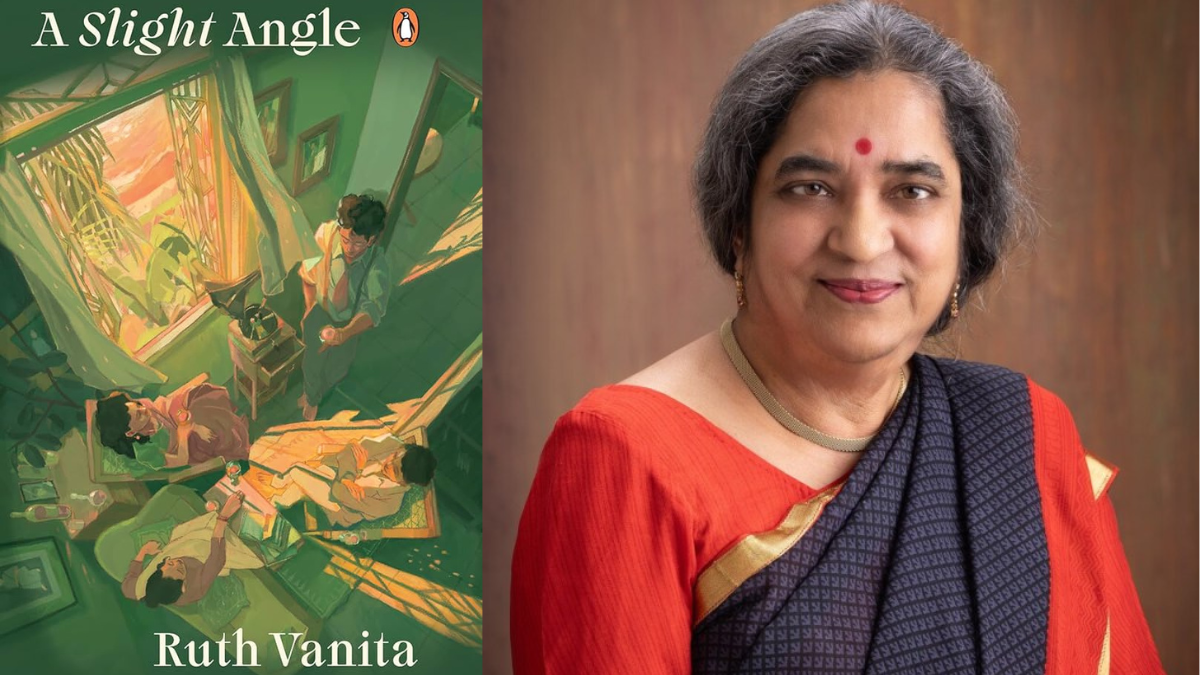

On the surface, A Slight Angle is many things: a historical fiction novel capturing Indian society in the 1920s, a mosaic of cameos with various luminaries of Indian literature interacting and intermingling like regular people, and an intersection of queer love stories in a society where external appearances had to be kept.

But what works for this novel, and what makes it more than a combined sum of all these aspects, is a deeply personal canvas upon which this landscape is painted.

Revolutions in the making: 1920s India as the backdrop

India in the 1920s was a delight for historians and a nightmare for history students. It was a time when political movements were gaining stronger traction, the death of Tilak was fresh in the memory, Gandhi had entered the stage, society was questioning and being questioned, society was reevaluating and restructuring itself while opposing the said restructuring and revaluations, attempts were being made to blur the religion and caste demarcations and yet religion and caste lines were becoming more pronounced, fueled by factors like the Khilafat movement, the Arya Samaj, and increasing religious nationalism.

The period was a tug-of-war between what people considered a glorious past, what was unanimously non-agreeable present, and dreams of a perfect future. It was a churn, a restless churn toward freedom.

But freedom in colonial India meant different things to different people. It constantly shifted and changed contours. For some, it meant freedom from the British Raj. For others, it meant freedom to live on their own terms. There were those seeking financial freedom, while another segment yearned to preserve traditions in a society they saw as rushing toward irreversible change.

Donning these different apparells of freedom and amidst these societal changes appear the many characters of Ruth Vanita’s second novel, A Slight Angle.

Portraits of desire: exploring the characters of A Slight Angle

There’s Sharad, a man of his own making, haunted by the boy he used to be. He moves through life, seemingly composed, but beneath the surface lies a tension between the roles he’s expected to play and the desires he dares not name. Torn between his familial duties and personal longings, he resides in the shadows of his past, where glimpses of a life lived for himself bewitchingly flicker.

Then there’s Abhik, a teacher whose wisdom is not enough to free him from the prison of his own making.

Then there’s Abhik, a teacher whose wisdom is not enough to free him from the prison of his own making. He understands the world through the lens of literature and art but cannot escape the emotional and ethical binds keeping him tethered. Abhik’s internal struggle is the quiet tragedy of a man who understands too much but allows too little.

Sheela starts her path to the elusive and undefined freedom with the crutches of Gandhism but gradually drops them as she moves through life, finding truer steps in her own shoes, albeit unorthodox. Her departure from Gandhism is not a rejection but rather a redefinition—freedom, for her, shifts and changes with each step.

‘She lived, it seemed to me, not so much in her body as in a room in her head that was framed by theories and ideals. When this ever-changing, cloud-like room collided with the physical world and the collision knocked her over, she brushed herself off and walked away.‘

–A Slight Angle, Ruth Vanita.

Kanta, on the other hand, is not disillusioned by her marriage; she is simply naïve, held fast by the chains of societal norms. Her dreams of a fulfilling marital life are clouded by her unshakable belief in the conventional scripts handed to her by tradition. She is bound not by what she lacks but by what she has been taught to expect.

Other characters, like Rita, a rising film star, Hemlata, an orphan with a curious mind, and Robin, a jazz musician seeking his place in a nascent film industry, weave in and out of the narrative.

The characters in A Slight Angle cross paths with each other, some walk together, others try not to, the intimacy palpable even in the denial thereof. Alongside, the social and political churns in the world around them also affect those interactions and journeys in subtle, nuanced ways.

The many faces of intimacy: personal, political, and ephemeral

‘… even though I long to say your name aloud to someone, I couldn’t have brought myself to say it to her. For now, you must be mine alone.‘

–A Slight Angle, Ruth Vanita.

Intimacy is a central theme of A Slight Anglel. Sexual intimacy, yes, but also the intimacy you share with your confidante, your city, and most of all, with yourself. From the emotional to the intellectual, intimacy is a recurring thread, binding characters to each other as well as to the spaces they inhabit and the internal terrains they travel.

The epistolary format, as it often does when done well, has a certain intimacy, and Ruth deftly uses that to her advantage. The diary entries and letters also allow a more passionate and erotic sensibility to course through the veins of this story.

Vanita’s depiction of intimacy in A Slight Angle is multifaceted—an ever-present force shaping the choices, desires, words, and silences of her characters. Writing from the perspectives of her characters allows her to explore individualism in a collectivist society. The characters tiptoe from one life to another, personal to public, both distinct from each other, colliding and colluding at the same time.

‘In a train one is not only alone but anonymous, ephemerally occupying the continual, inescapable passing of all things.‘

–A Slight Angle, Ruth Vanita.

Bridging scholarship and fiction: Vanita’s exploration of queer history in fiction

Vanita brings her extensive knowledge and subject matter expertise in literature and history here, having co-edited the landmark piece Same-Sex Love in India, as well as editing and translating On the Edge: 100 Years of Hindi Fiction on Same-Sex Desire.

Moreover, she’s also translated the works of authors who feature prominently in her novel, such as Mahadevi Verma’s My Family and Chocolate and Other Writings on Male Homoeroticism by Pandey Bechan Sharma ‘Ugra’. In a way, A Slight Angle is a coming-together of her work through the years.

Various sections unfold like a reader’s utopia, with characters quoting Shakespeare, Wilde, and Sappho as they try to understand themselves through those themes and authors and, in turn, make sense of the volatile world they inhabit.

Love, rules, and rebellion in A Slight Angle

The love laws, to borrow from Arundhati Roy, that ‘lay down who should be loved, and how, and how much,‘ persist and prevail in our society well into the 21st century. Ruth Vanita’s A Slight Angle takes us back by a century to a time when these conversations quietly simmered beneath the surface. It’s also a reminder of how much and simultaneously how little we’ve evolved.

Ruth Vanita’s A Slight Angle takes us back by a century to a time when these conversations quietly simmered beneath the surface.

Perhaps the novel’s strength lies in its insistence that love, no matter how quietly spoken or secretly held, always finds a way to exist, survive, and speak.