In the past few years, only sheer hopelessness has characterised the collective psyches of the upholders of justice and freedom. David Graeber the renowned anthropologist and activist and one of the main organisers of the Occupy Wall Street Movement in 2011 asserts that this hopelessness is manufactured. The world system of property, patriarchy and border colonialism deploys a huge amount of military and police forces, creates inter-ethnic strife through jingoistic rhetoric, and adopts extremely sophisticated surveillance technologies to colonise our bodies. They aim to stifle our creativity and ability to organise our lives across emancipatory principles.

But there is something stubborn about hope. It just refuses to give in. The commitment of several human beings towards human liberation can transform any moment of doom into Kairos, the moment of transition of creation. And the creation at such times that is both elegant in its beauty and firm in its willingness to shatter all barriers is music.

Our values of solidarity, resistance and hope, are best expressed through art especially music because music in its vocal, instrumental and performative aspects provides our bodies with the opportunity to refuse bio-political control by the military, capital and organised religion. The composition of dissident music has and continues to enable the oppressed to transcend the semiotic prisons of the oppressor.

Music has historically been the unifying cultural element of moral and political society; the repressed substratum of all societies based on the concentration of power and exploitation of labour. It is in these moral and political societies alternative and radical forms of sociality are created and recreated. It enables marginalised groups to create their signs, symbols and values that are autonomous from the value system of the oppressive systems. The performance of such music enables ‘otherised,’ groups to heal themselves physically, psychologically and spiritually in the face of severe violence by power structures and strengthen their collective solidarity.

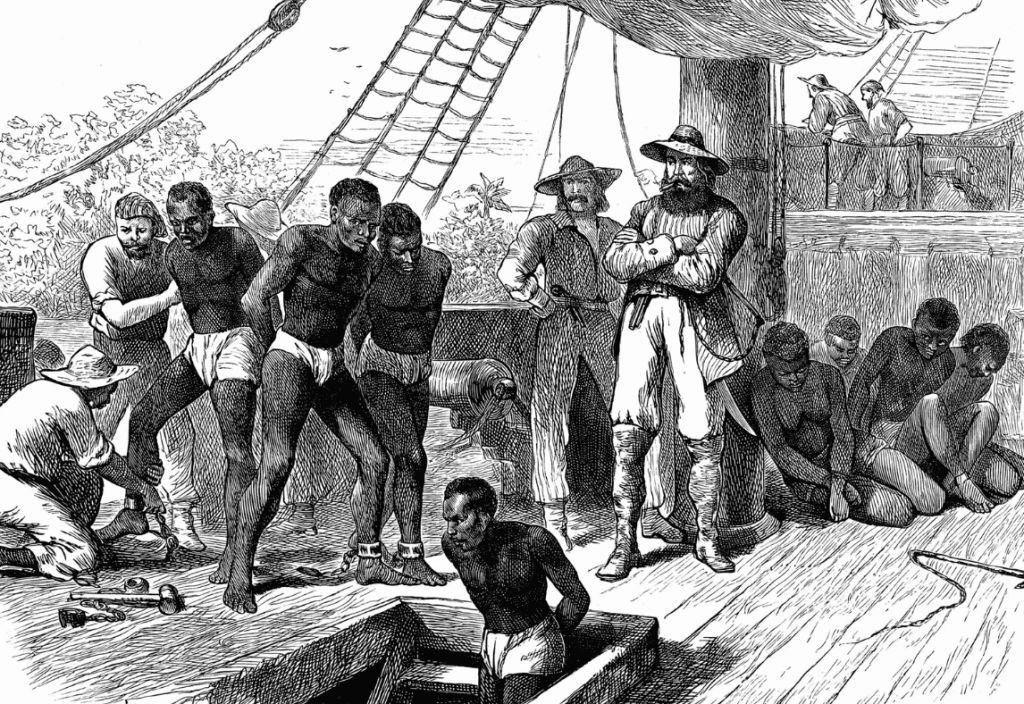

In the United States, the first generation of slaves were barred from speaking their native language. Due to the multiplicity of native African dialects, the slaves found it extremely difficult to communicate. Gradually they picked up bits of words and phrases from English reinvented them in a way that was more relevant to their lived experiences and modified it. The English they produced were thus lexically different from standard English with novel configurations of words and phrases. This is the English that is heard in Jazz and spirituals of the African Americans. They thus reclaimed English as a language of resistance, of community.

The Dalit community creates its praxis of resistance through music. Dalit music is deeply connected to the land, to physical labour to the exploitation of Dalit minds and bodies. Relations with land and production constitute the central theme of Dalit music for it tells the story of a people whose manual labour has been exploited over centuries but they have been deprived of land and other means of production by Brahminism. The landscape is a significant part of Dalit music wherein entities like forests and rivers are visualised as having lives of their own as elements that could move, speak and be a part of the broader human community.

Dalit demigods like Chuhadmal and Dina, Bhadri Baba and many spirits also make up a significant section of the content of Dalit music. This tremendous vitalism embedded in the lyrics and notations signifies the elaborate systems of meaning subaltern people can create to provide them with the hope to continue their lives. The aesthetic fabric of Dalit music does not stand on the binary between physical and mental labour. One such form born out of the experience of bodied labour is Bidesiya art of Bihar. It was founded by Bhikhari Thakur a former migrant labourer from Bihar whose art performances amalgamated many vernacular traditions and the experience of migrant labourers.

The music of Dalits and African Americans is a testament to the capacity of human beings to create and recreate multiple forms of alternative sociality amidst severe repression. The production of this music has been going on for centuries even before the formal structures of democracy were in place. Present-day struggles need to effectively derive lessons from these registers of dissent.

On 21st February 2012 the Russian Police in Moscow arrested Yekaterina Samutsevich, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina belonging to an anarcho-feminist punk band Pussy Riot. Their crimes? They openly called out the corrupt links between the Russian Orthodox Church and the autocratic President Vladimir Putin. Their criticism of Putin was not their only crime rather the visual aspect of their performance threatened Russia’s patriarchal oligarchy. These women performed the song Punk Prayer in front of the Christ the Savior Cathedral in Moscow wearing the so-called immodest dress that exposed their arms and legs and used profanity in their song. The horrified establishment called for severe sexualised violence against these women as punishment.

Pussy Riot is one among several feminist punk bands like King Kong Meuf, Killing Pixties, and Ternura all over the globe that are defining the essence of femininity amidst the violent onslaught of capitalist patriarchy wherein the market increasingly commodifies women’s bodies, far-right populist groups deny access to reproductive justice and religious fundamentalists crack down on pro-queer curriculum in schools. These are groups associated with not just art but in building communities, mutually caring for one another fighting the system through the open visualisation of nonconformity in dress, language and lyrics. These groups are inventing newer forms of agitation and belonging within their organisations.

It is perhaps best to conclude with Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s verse:

“Lambi hai gham ki shaam magar shaam hi to hai“

The night of despair seems too long but it is only night after all.

About the author(s)

Rohin Sarkar (preferred pronouns: he/him) is an eighteen year old teenager obsessed with critical theory, Anarchist studies and Ambedkarite literature. His passion other than academics include poetry by Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Habib Jalib along with Anarchist punk by David Rovics. He also enjoys Oxford style and British Parliamentary debating because it enables him to speak his mind without fear of being censured. When not studying or debating he is chatting on politics with his friends either on WhatsApp or in the college premises.