E. Abubakar and A S Ismail, the two leaders of the Popular Front of India (PFI) were arrested as political prisoners on September 22, 2022, along with more than 100 activists from different parts of the country under a case which the National Investigation Agency (NIA) popularised as the “largest ever” investigation process.

E. Abubakar was the founding member and the first chairman of the Popular Front of India, while A S Ismail was the member of the National Executive committee of the PFI. Following the mass crackdowns on the organisation, the PFI was banned on 28 September, 2022. Organisations affiliated with it, including the Campus Front of India, National Confederation of Human Rights Organisations, National Women’s Front were outlawed, citing “unlawful associations” by the union government.

Imprisoned for over two years, A S Ismail and E. Abubakar have been enduring prolonged detention despite their worsening health.

Imprisoned for over two years, A S Ismail and E. Abubakar have been enduring prolonged detention despite their worsening health. Recently, their families, along with the family of Professor P Koya, who was arrested in the same case, and the General Secretary of the National Confederation of Human Rights Organisations, formed a coalition to raise concerns about their prolonged imprisonment without trial.

‘We are particularly concerned for the life of E. Abubakar and A S Ismail‘, the families wrote, drawing attention to the plights of their imprisoned family members who were arrested under UAPA. The case, being spearheaded by the National Investigation Agency, has raised concern about the justice meted out to political prisoners and the deliberate neglect they endure through a process that often serves as a form of punishment.

Rights stifled, denied medical care in prison

On September 20, the Supreme Court sought a response from the NIA regarding a bail plea filed by E. Abubakar. The court noted that it would consider the bail solely on medical grounds. Earlier, on May 28, the Delhi High Court had rejected his bail application, stating that the allegations against him were “prima facie” true.

Abubakar approached the Delhi High Court after his bail application was rejected by the Trial Court. In May, the Delhi High Court, headed by the bench of Justice Suresh Kumar Kait and Justice Manoj Jain, upheld the charges against him of orchestrating, through PFI, the establishment of a Caliphate in India by 2047 through a Jihad against the Indian Government.

The High Court, based on the statement of the “protected witnesses” and the material collected by the NIA during the investigation, remarked that ‘it cannot be said that the allegations were merely to the extent of ideological propagation of the activities of PFI. It was certainly much more than that‘.

In October 2022, Abubakar applied for bail on medical grounds. The Trial Court, rejecting the bail, directed the Jail authorities to avail medical needs to him, but he was never admitted. The Delhi High Court, citing the previous judgment, highlighted that he could be shifted to the AIIMS, although his bail on medical grounds was rejected once again, after which he moved to the Supreme Court.

In 2019, Abubakar was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer called Gastroesophageal Junction Adenocarcinoma. He underwent extensive treatment, including chemotherapy and surgery, in which 80% of his abdominal and intestinal area was removed.

He underwent extensive treatment, including chemotherapy and surgery, in which 80% of his abdominal and intestinal area was removed.

Despite facing life-threatening risks, his bail has been rejected every time. In court, Abubakar has raised concerns over his illnesses and his old age. Like Father Stan Swamy, the oldest political prisoner to fall victim to institutional murder, Abubakar is also a patient of Parkinson’s, in addition to hypertension, diabetes, and vision loss.

‘He has never received the treatment he needed. He is prone to tremors, slowness of movement, depression, fatigue, dementia, sleep problems, anxiety. It’s a lot more than to describe‘, the family of Abubakar wrote. The neglect he has faced, despite suffering from several life-threatening illnesses adversely violates his fundamental rights. ‘There is no likelihood of the trial concluding during his lifetime. The possibility of the trial commencing in the near future in the present case is also bleak‘, the family stated.

On 12 November, the Supreme Court directed the AIIMS to constitute a medical team for a thorough examination of E. Abubakar, to ascertain if he deserves bail on medical grounds. His last hearing, scheduled for 29 November in the Supreme Court, was postponed and rescheduled after the winter vacation of the Supreme Court.

In Javed Ghulam Nabi v. State of Maharashtra, the Supreme Court held that ‘If the state or any prosecuting agency, including the court, has no wherewithal to provide or protect the fundamental rights of an accused to have a speedy trial as enshrined under Article 21, then the plea for bail can’t be opposed on medical grounds, irrespective of the nature of the crime.‘

While death looms around E. Abubakar, A. S. Ismail is imprisoned in a paralysed state. In a conversation with us, Surjan, Ismail’s nephew, said, ‘He was all good with health, until he was lodged in a fabricated case.’

On the morning of September 20, his family in Tamil Nadu received the information that he suffered a heart-stroke, which left his right-side completely paralysed.

On the morning of September 20, his family in Tamil Nadu received the information that he suffered a heart-stroke, which left his right-side completely paralysed.

‘The blood was oozing out from both of his ears when I attended him at the hospital‘, Surjan said. ‘They administered first-aid and shifted him to Safdarjung Hospital after we pleaded with them for his life. But two days later, he was taken back to the prison, without receiving any treatment,‘ he said.

The efforts that political prisoners have to make to go through several processes and orders only make timely access to healthcare impossible. ‘We have been requesting proper treatment for him, but even his MRI and CT scan haven’t been done. They’re just giving him doses without any diagnosis or treatment,‘ Surjan shared.

After being paralysed, Ismail couldn’t even move his body. He needs the support of an attendant for even basic needs. On the first of November, he was taken to the Apollo Hospital in Delhi again, but his stay lasted only 6 hours before he was taken back to the prison, to await an unprecedented relief.

Prolonged political imprisonment: a process served to kill

On 29 November, we met Umar Khalid at the Karkarduma court as his case was listed there. He entered courtroom no. 58 with a glaring smile, in his usual way, hiding his worries as Banojyotsana, his partner, and friends waved at him in solidarity.

In the courtroom, we asked him if he knew what E. Abubakar and A. S. Ismail were going through in the Tihar Jail, where he is also imprisoned. The judge interrupted, and I couldn’t get a response from him.

‘Can I take a minute to hold a conversation?‘ he asked the judge sincerely while he was occupied in reading.

‘Take 20,’ the judge replied. We sat in a row, separated by a guard between us.

‘I had to take rounds of the courts for a year to secure a dental appointment. That’s how long it takes here. You are forced to die through interminable processes and checks before you’re allowed to pursue a treatment,‘ Umar told us.

We listened to him speak his heart out, as a political prisoner who has been denied bail more than 15 times, and whose trial is yet to commence. ‘Jail is a brutal experience. The bureaucracy has a vulgar apathy. They perform formalities, take the patient to the hospital, and then withdraw them to the prison claiming that they have been administered the medicines,‘ Umar said.

We listened to him speak his heart out, as a political prisoner who has been denied bail more than 15 times, and whose trial is yet to commence.

We asked him how a lengthy process bars the patient’s immediate requirement for medical care.

‘There was an old experiment carried out with two different rats. One was kept free and the other one was caged. The caged one dies due to isolation and enforced confinement. The most prevalent use of this experiment is applied on the political prisoners to kill them. In prison, the medical care is not provided to the ailing political prisoners. Adding to that, due to isolation, depression ensues and physical health deteriorates. It ends up making the person endure a form of oppression, solely intended to kill them. Political imprisonment is a poison. It is meant to repress a person’s will to fight against injustice‘, Umar responded.

‘No more G.N Saibaba, Pandu Narote, Stan Swamy, Kanchan Nanaware’

When Professor G. N. Saibaba was acquitted in March after bearing jail for 10 years, he said that ‘The inhuman treatment meted out to me during the imprisonment, which amounted to torture, put my life at risk. I was denied medical care. It has left me a physical wreck. Today, I am alive before you but my organs are failing me‘.

The suffering he endured during his prolonged incarceration eventually took his life within 7 months of his release. Once again, it was the failure of the state in denying a 90% disabled person the care he needed. Ultimately, no evidence was found against him for “Alleged Maoist associations” after his body had already failed to function.

Vasantha, Saibaba’s partner, talking about his health and the neglect he faced during imprisonment, told us, ‘I’d take the medicines for him, but the jail authority didn’t give it to him. He was not released on medical grounds despite contracting COVID and suffering from several life-threatening illnesses.’

Pandu Narote, a 33-year-old Adivasi from the Gadchiroli district, who was arrested in the same case as Saibaba, passed away after contracting swine flu in prison in August 2022. Imprisoned for over 8 years, he was denied medical care and convicted under various terror laws alongside Saibaba in 2017. Despite the absence of evidence for the alleged crime, he did not live to experience freedom again.

Narote’s lawyer, Akash Sorde, had said that his family was not informed about his deteriorating health. ‘There was blood in his vomit and urine. They waited until the last minute, when he was already on his deathbed, to shift him to the hospital. It was too late,’ Sorde said. Pandu Narote’s death, in its own right, was believed to imply that the institutional murder of Professor Saibaba was a virtual certainty.

Pandu Narote’s death, in its own right, was believed to imply that the institutional murder of Professor Saibaba was a virtual certainty.

Kanchan Nanaware was the first casualty of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). A 38-year-old activist and Adivasi from the Chandrapur district in Maharashtra, she died in custody in January 2021 after awaiting trial for six years. All of these victims of institutional apathy were deliberately denied medical treatment, only taken to the hospital when they were close to death.

Nanaware was kept in Yerawada Jail for six years, where her health deteriorated rapidly under solitary confinement. Arun Bhelke, her husband, who was also lodged in Yerawada Jail, was allowed to see her only once during those six years.

The doctors had recommended that she needed an immediate lung transplant, but the judiciary rejected her bail each time she applied despite its knowledge of the severe risk to her life.

On 16 January 2021, Nanaware was taken for brain surgery, but her lawyer and Bhelke were not informed. The jail superintendent falsely signed consent papers for the surgery claiming that no relatives could provide consent. Bhelke found out about his wife’s critical condition 2 days later on 18 January through fellow prisoners who passed the information on to him. He had to approach the court to see his wife. 5 days later, on 23rd January he finally saw her in Pune’s Sassoon hospital. She was in a critical state, unable to recognise or speak to him. She died a day later.

It is imperative that bail be granted to E. Abubakar and A. S. Ismail, as the deliberate pattern of neglect they have faced, along with the allegations against them, clearly paints a vivid picture of systemic injustice that shows no signs of ending in the foreseeable future.

‘We don’t want any more Saibaba, Narote, Nanaware, Stan‘, Vasantha said. ‘Does the state want to murder them like Stan and Sai and others?. They should be immediately released so that they don’t suffer the fate of those who were punished through incarceration without any evidence‘, she said.

A sugar-coated death-sentence for political prisoners

While the content of evidence has been a matter of contestation in the cases of political prisoners, the authenticity of the sources and material has also been disputed. Human rights activists and agencies have revealed a motivated attempt by the government to present evidence that does not align with the truth of the matter.

In Saibaba’s case, the Bombay High Court ruled that no punishment could be imposed on him, as the entire process of recovering evidence was flawed. The police had made an illiterate person a witness and prepared the Panchnama (a document recording crime scene details). The court stated that such evidence could not sustain the case and that serious allegations could not be based on such a weak procedure. Despite this, for 10 long years, the investigation agency opposed his bail, even though no evidence of the alleged crimes existed to justify his punishment.

Father Stan Swamy’s bail was opposed by the NIA, claiming that there was no conclusive proof of his illness. Eventually, it put him on the verge of death. Justice S.S. Shinde of the Bombay HC, who consistently denied bail to Stan Swamy, was forced to retract statements he made praising him after his death, following objections from the NIA. The agency claimed that such statements were creating a “negative perception” against it.

It was later revealed that all the “purported” evidence against the 84-year-old man were fabricated. In December 2022, the evidence of planting several incriminating documents were found by the forensic company- Arsenal consulting. ‘Stan was the target of an extensive malware campaign for five years… right until his devices were seised in 2019‘, their report stated.

In July this year, ASG Raju opposed the bail application of Abdul Razak Peediyakkal, saying he posed a threat to national security.

In July this year, ASG Raju opposed the bail application of Abdul Razak Peediyakkal, saying he posed a threat to national security. The Supreme Court, however, disagreed with the ASG and remarked ‘the nation was not that weak‘. Similarly, Majority of the political prisoners have been alleged to be a threat to “national security”, a reasoning that enforces prolonged incarceration, neglecting their medical needs.

These defenders of human rights were forced to die, the process has continued unabated. Rona Wilson, a political activist and human rights’ defender who was also a member of Committee for Release of Political prisoners was arrested under UAPA in 2018 in connection with Bhima Koregaon violence.

In his case too, reports of planting incriminating documents and surveillance by Pegasus have been confirmed. A NetWire RAT (Remote Access Trojan) was used ‘for purposes of both surveillance and incriminating document delivery‘, a report of the Arsenal stated. His bail was opposed in July 2021 by the Pune Police, which sought quashing of the charges, claiming that the charges were based on material that was allegedly planted on his electronic devices.

On September 5, the NIA arrested Advocate Ajay Singh, an intellectual and anti-displacement activist from Chandigarh. Ironically, there was no mention of his name in the FIR related to the Northern Regional Bureau case. ‘When we opposed the arrest, they changed the name ‘Aman.’ They wrote ‘Ajay Alias Aman’ in the FIR later,‘ Advocate Aarti, Ajay’s partner and member of The Punjab and Haryana High court Bar Association, said.

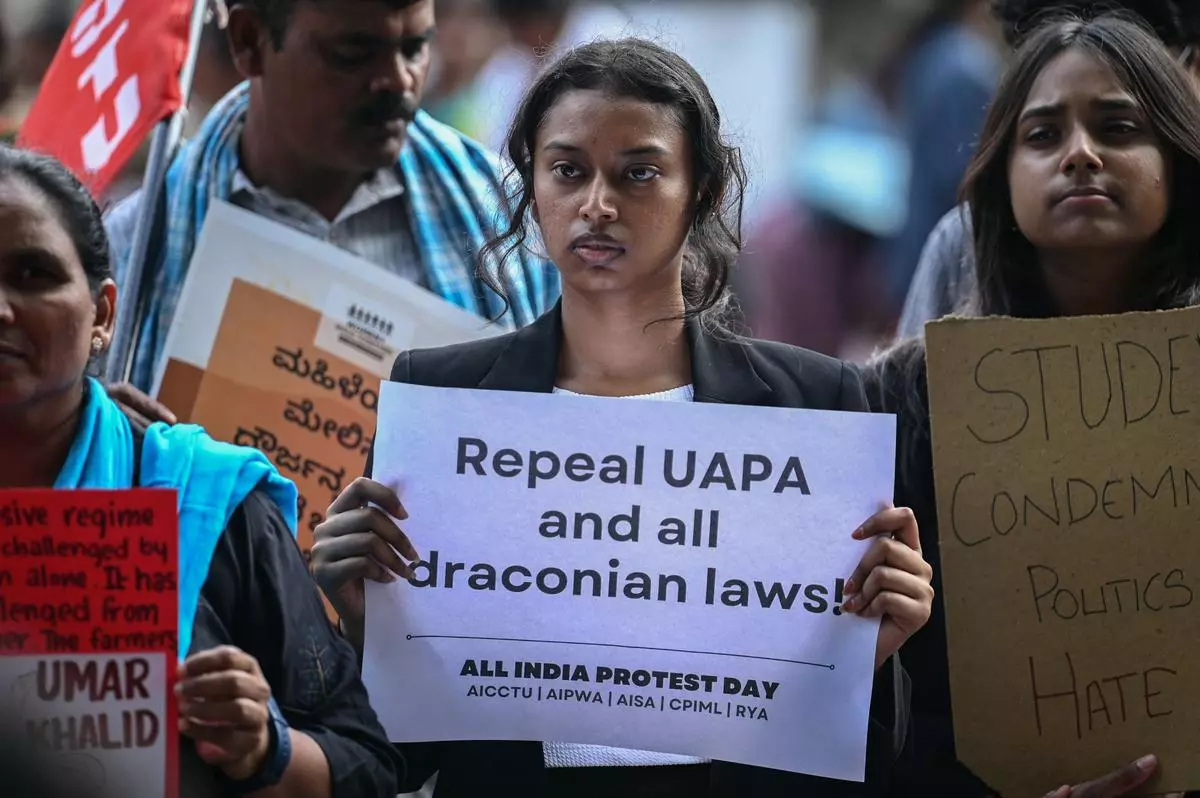

The UAPA has been opposed for a number of its inconsistencies. Human rights activists have contended that it is an attempt to silence all those who dare to speak against injustice across the country—whether it be atrocities against Muslims and Dalits, corporate plunder of Adivasi lands, or repression.

‘Earlier, the FIR used to be the basis of the allegations. Now, the allegations are first stamped, based on which FIRs are filed. They hatch a story first, according to which their interrogation is carried out. They use the accused and make them the protected witnesses to fulfill the needs of a story fabricated by them. The entire plot is created along these lines‘, Advocate Aarti said.

One major criticism of the UAPA is its low conviction rate. Between 2014 and 2022, 8,719 UAPA cases were registered across India, but only 222 led to convictions. In these 8 years, 14,809 individuals were arrested under UAPA, yet charges were proven against just 356.

These numbers highlight that the most prevalent use of the law is to silence political dissent, stifling democracy.

These numbers highlight that the most prevalent use of the law is to silence political dissent, stifling democracy. ‘As repression escalates, conviction rates will rise to establish authenticity. This will be supported by protected witnesses, who are used to reinforce charges in special courts,’ Aarti said.

The UAPA, described as a “sugar-coated death sentence,” has increasingly sparked democratic resistance in recent years. From the cases of Saibaba, Bhima Koregaon, and the Delhi riots to the PFI crackdown, the charges leveled against political activists reveal a disturbing pattern of repression targeting the country’s most marginalised voices and communities fighting for justice.