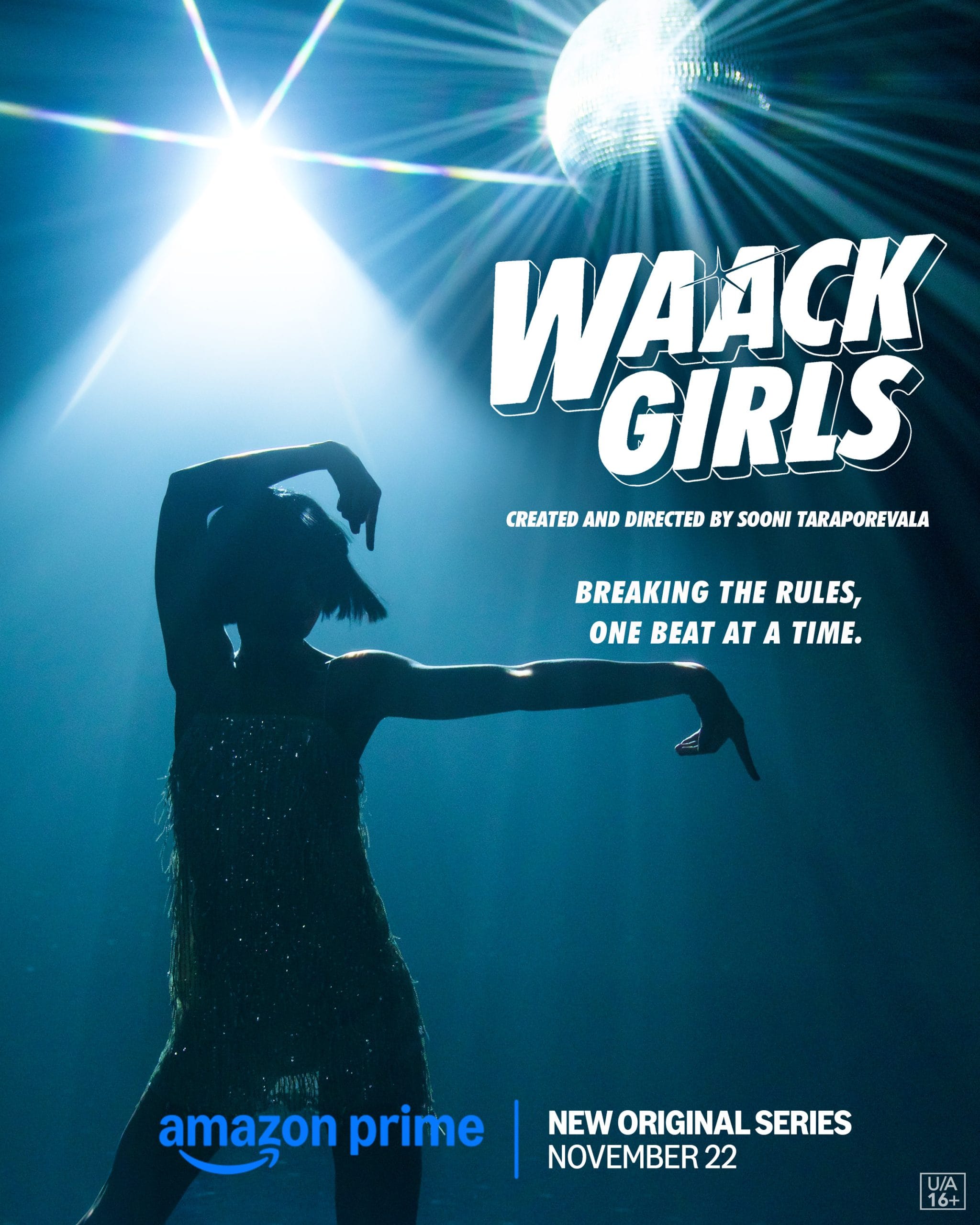

Waack Girls on Amazon Prime is not only profound and fun in equal measure, but it also does the important work of mainstreaming a little-known facet of queer culture, all the while successfully avoiding the choice-feminism and girlboss traps that many shows about women succumb to. The show, set in Kolkata, follows an all-girl waacking group, managed by a feisty novice. It stars Rytasha Rathore as manager Lopa and Mekhola Bose, Anasua Chowdhury, Priyam Saha, Ruby Sah, and Chrisann Pereira as the five-member troupe that is the Waack Girls. Other cast members include cinema veteran Barun Chanda, Achintya Bose, and Lillete Dubey. The show is created by Sooni Taraporevala.

The show is a nuanced, careful, and heartfelt tale about women and their exploration of self, their rejection of societal expectations, and their resistance against being forced into boxes. Lopa (played by Rathore) is an openly gay woman fighting her family’s homophobia; Ishani (Bose) is a caregiver to her ailing grandfather and the family’s breadwinner; LP (Chowdhury) moves cities to live on her own terms away from her family’s control; Michke (Saha) is consistently battling the performance of femininity her overbearing mother expects of her; Anumita (Sah) feels trapped between her love for dance and her father’s insistence on her pursuing a career in gymnastics; and Tess (Pereira), by joining the troupe, has the opportunity to find herself and explore a budding relationship after dedicating years of her life to caring for her mother who is dealing with a gambling addiction.

While the circumstances of each character are radically different, one thing holds true for them all: they are all fierce, unapologetic women who hold their ground.

While the circumstances of each character are radically different, one thing holds true for them all: they are all fierce, unapologetic women who hold their ground. And waacking serves as the perfect setting for this. But to understand Waack Girls any further, it is essential to first understand the history of waacking.

Origins of waacking and waacking as the perfect backdrop

Waacking originated in the queer clubs of Los Angeles in the 1970s, at a time when these underground clubs were one of the few places for queer folks to be themselves and express themselves authentically. It was pioneered by gay men of colour as a form of fierce and authentic self-expression but came to symbolise queer liberation, resistance, and defiance in the face of oppression and homophobia. Waacking evolved from the dance form initially known as ‘punking’, a name that sought to reclaim the word punk, which was derogatorily used against gay men in the era.

Abhilasha Jain, an Indian-origin dancer and choreographer based in San Francisco noted, ‘In the 70s, it [waacking] was a beacon for queer communities, a way to reclaim joy and assert individuality in the face of societal rejection. Today, while the context may have evolved, that self-expression and defiance remain at its core.’

The AIDS epidemic of the 80s saw all but one of the originators of the dance die and waacking found itself relegated to the shadows. By the turn of the century, there were few waackers, and the dance had become an obscure cultural relic of queer history, but it was revived by dancer Brian Green when he began teaching it in New York City in the early aughts with the help of one of the original pioneers of the dance form, Tyrone Proctor.

The term waack originated from the onomatopoeias such as ‘whack’ found in comic books. Waacking incorporates rapid and forceful but controlled arm movements and theatrical poses, with dancers exuding confidence and fierceness. Integral to waacking is expressing the music through the movement. Princess Lockeroo, an internationally recognised waack performer, said in a video, ‘Waacking is making the music visual.’ Tyrone Proctor in a 2010 interview said waacking drew inspiration from 40s Hollywood and drag queens.

Speaking of what stands out to her about the dance form, Abhilasha Jain said, ‘I was mesmerised by the grace, power, and confidence of waackers. I came to see waacking as extraordinary because of how dancers weave a story with their movements, informed by who they are at their core. It’s a celebration of individuality. No two waackers ever look the same and that, indeed, is the beauty of this form.’

While waacking has gained increasing popularity in recent years; in India, it remains a niche dance form that is yet to be mainstreamed, and perhaps Waack Girls can change that.

While waacking has gained increasing popularity in recent years; in India, it remains a niche dance form that is yet to be mainstreamed, and perhaps Waack Girls can change that. While there exists a dedicated waacking scene in India, with dancers who excel at the dance form, Waack Girls stands out because it is the only piece of Indian media in recent memory that brings to the fore a part of queer history for an Indian audience.

Abhilasha, when asked what waacking’s roots in resistance and authentic self-expression mean to her as a woman, said, ‘I don’t like to be put in a box. Waacking allowed me to be free and discover my own unique style of movement which was very liberating. It gave me a way to express my femininity, to be vulnerable, to experiment and weave in elements of my culture, and create something deeply authentic to who I am.‘

As Abhilasha suggests, central to waacking are ideas of liberation, resistance, defiance, authentic self-expression, and a sense of empowerment. What better anchor then for Sooni Taraporevala’s Waack Girls? In Taraporevala’s own words it’s a show about ‘young women standing their ground‘ and that tale is best told through a dance style rooted in ideas of liberation and resistance of the marginalised.

Ishani, in the show, initially takes up waacking at a time when she feels no control over her life after the loss of her parents and sister. Waacking helps her gain a sense of control, just as it does for the other waack girls. All of them experience some level of lack of control: Tess with her mother’s gambling, LP with her precarious financial situation, Ishani with her grandfather’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis, Michke with her meddling, body-shaming mother, Anumita with being forced into a career she doesn’t enjoy, and Lopa with her parent’s homophobia and refusal to accept her sexuality.

Waacking then provides all the girls with some semblance of control. It not only is empowering, but as women, waacking’s origins in embracing authenticity and resisting narrow societal expectations speak to their personal struggles and shared experience of navigating a patriarchal world.

What Waack Girls gets right

How Waack Girls seeks to define and explore empowerment makes it stand out. Tired, overly simplistic depictions of women’s empowerment, that are rooted firmly in choice feminism and little else, dominate Indian film and television. Depictions of empowered women often play into a capitalistic fantasy of being a girl boss and having it all, but doing so while adhering to traditional expectations of femininity and operating, for the most part, within patriarchal frameworks.

All the women in Waack Girls are navigating constraints placed on them by a cisheteropatriarchal world, but this is depicted in ways that go beyond the shallow girl-boss feminism of similar shows, where empowerment is relegated to peripheral matters of clothing or sexual politics.

Waack Girls doesn’t fall into this trap. The show’s understanding and depiction of empowered women is authentic, relatable, and ultimately, much more meaningful. All the women in Waack Girls are navigating constraints placed on them by a cisheteropatriarchal world, but this is depicted in ways that go beyond the shallow girl-boss feminism of similar shows, where empowerment is relegated to peripheral matters of clothing or sexual politics.

Waack Girls’ depiction of empowerment and women’s agency, whether through Anumita or LP standing up to their families and pursuing their dreams or Michke and Lopa being their authentic selves and rejecting narrow constraints of femininity, is not only much more narratively rich but reflects the experiences of a majority of Indian women.

Waack Girls also consciously and consistently rejects any performance of femininity. Most of the female characters on the show don’t conform to traditional ideas of femininity. They aren’t agreeable; are often angry, opinionated, loud, and headstrong; and most importantly, refuse to concede their agency or externalise their autonomy to anyone, especially to their families. And Waack Girls celebrates this and relishes in it.

The show also has a refreshing disregard for the male gaze. Within its universe, the characters never seem to play into the male gaze, nor do they seem conscious of it at all. And the show itself seems to completely disregard it, with the characters never sexualised or performing for male desires or validation.

Not only does it reject the male gaze, but it doesn’t centre men the way a lot of shows about women do. While one would expect shows about women to centre them, an astonishingly large number of shows about women centre men and even fail the Bechdel Test. Shows like Four More Shots, Please or Sex and the City, touted as shows centring women, are about women – but barely. Major plot points often revolve around female characters seeking the attention and validation of male characters. In Four More Shots, Please, three of the four characters’ plotlines revolve, in one way or the other, around men and romantic relationships.

But while Michke’s self-worth comes from within, Siddhi’s self-acceptance is rooted in repeated male validation.

The two shows’ depictions of body positivity also stand out starkly. In Fourt More Shots, Please, Siddhi (played by Maanvi Gagroo) has an overbearing mother who constantly body-shames her and reduces her worth to her marriageability, much like Michke in Waack Girls. But while Michke’s self-worth comes from within, Siddhi’s self-acceptance is rooted in repeated male validation.

Waack Girls also does a better job than most Indian film and television in representing characters from various class locations. The show doesn’t explore class greatly but takes a nuanced approach to the subject whenever it does. However, it explores how class creates hurdles in embracing authentic self-expression. Lopa is able to easily give up the opportunity to attend university in the United States to follow her dream of managing the Waack Girls. However, a character like Anumita, who doesn’t come from wealth like Lopa, is forced to continue her gymnastics training – even though she immensely dislikes it – because of the prospect of future employability.

Where Waack Girls Falls Short

Waack Girls does a good job of representing various body types, but it fails to treat them all the same. Michke (played by Priyam Saha) experiences some body shaming in the show and the treatment of the character has undertones of fatphobia. While the body-shaming Michke is subjected to by her mother is portrayed as problematic, fellow Waack Girl LP also body-shames Michke multiple times in the first few episodes.

And this isn’t limited to one character. When the characters of Michke and Anumita first meet, Anumita is surprised by Michke being part of the troupe, with the subtext being that Michke’s weight makes it unlikely that she can be a dancer. None of this serves any narrative benefit and was quickly forgotten once the girls started getting along a few episodes in. Michke is also portrayed as having a preoccupation with food, often eating or thinking of food. This, of course, is played for laughs but was unfunny, unnecessary, and problematic

While Michke plays the caricaturised fat, yet assuredly body-positive, woman, the other waack girls can sometimes seem like stock characters. Anumita plays the meek, lower middle-class girl with moments of fierceness. LP plays the cliché of the independent girl who is obstinate to the point of impracticality. Tess is one-dimensional with little more to her character than her contentious relationship with her mother. The characters could benefit from being fleshed out more and the addition of more complexity and interiority.

Even with its few failings, Waack Girls is a delight. The show has far more to recommend it than not, getting much more right than wrong. It not only brings waacking and its queer roots to the fore, but it also is a celebration of its ideas of liberation, resistance, defiance, and authentic self-expression. Waack Girls is also an ode to women and their rejection of gendered expectations and sexist limitations with spirited defiance and the refusal to concede to a cisheteropatriarchal world’s idea of who they ought to be.

About the author(s)