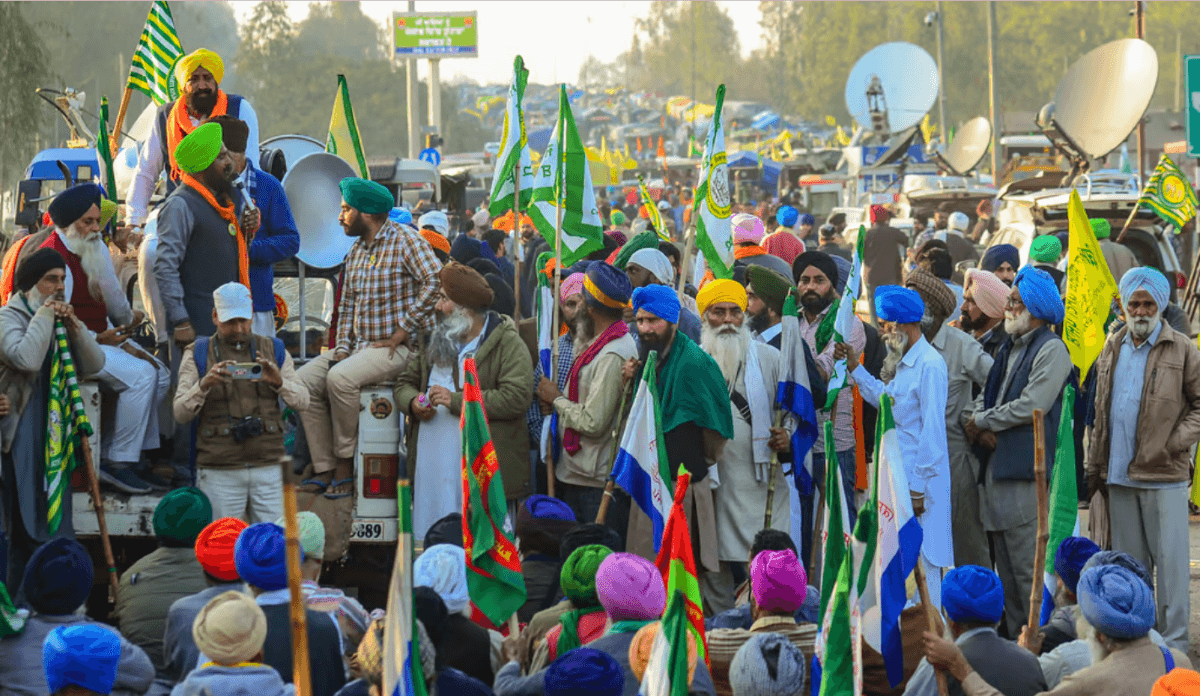

On December 6, 2024, protesting farmers from Punjab were stopped at the Shambhu border and not allowed to reach Delhi. They were met at the Haryana border with police barricades, tear gas, and brutal force. The ‘Dilli Chalo’ march started a few days ago and has faced obstacles from the police ever since. At the Shambhu border in Haryana, police used tear gas to try and stop the farmers from continuing their journey towards the national capital. They also suspended mobile internet services along the path to prevent protesters from communicating.

There have been claims of police brutally using tear gas pellets not only to deflect but also to hurt the farmers. Farmer leader from Punjab, Sarwan Singh Pandher, asserts that police pellets critically injured at least eight farmers, and one of them was rushed to the Post-Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER) in Chandigarh.

Dilli Chalo march suspended

As a result of the brutal force, the farmer leaders suspended the foot march to Delhi on Sunday afternoon. Pandher adds, “We have called back the jatha (group of 101 farmers).” The group of farmers, labelled as marjeevras (someone willing to die for a cause), was marching for a legal guarantee for Minimum Support Price and were willing to be heard in Delhi when they were stopped by Haryana security personnel a few meters away.

The march was an extension of the farmer’s protest; it was designed to grab attention and speak about their rights directly to the power so they were heard. “The farmers are protesting for better prices for their crops, debt relief, and the repeal of certain farm laws they believe are harmful to them – today’s march is a part of their ongoing struggle to get the government’s attention,” reports News 24.

The police’s forceful tactics to drive the farmers away have only bolstered their determination to persevere and carry on with the march. Despite the tear gas, the protesters are committed to making themselves heard in the capital. The ‘Dilli Chalo‘ march is an effort to bring the farmers’ issues directly to the government in Delhi.

Tense situation at the border

The situation at the border remains tense after the Sunday afternoon clash between police and the protesters as both continue to hold their positions. While the protesters are firm on their demand, the government has yet to announce any plans to meet with them.

The farmers’ protest has aged; it has been almost 10 months since they protested in their state and seven days since the protest reached the borders of Delhi. While the government has shown no interest in having a dialogue with the protesters, their representatives continue to malign the protest.

“It has been 305 days since Delhi Andolan 2.0 started and seven days since the ‘Amar Anshan.’ The ministers are making irresponsible comments,” said Pandher in an interview with ANI.

Identity of Farmer Protesters

The Delhi march is a part of a call given by farmer unions Samyukta Kisan Morcha (non-political) and Kisan Mazdoor Morcha. “The Haryana police asked the farmers not to proceed further. They cited a prohibitory order clamped by the Ambala administration under Section 163 of the Bharatiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) that bans unlawful assembly of five or more people in the district,” says PTI.

The police state that the number of protesters in the march is overwhelming and doesn’t comply with the permission granted for the jatha, i.e., 101 farmers. The protesters at the site have complained of police officials demanding identity proof to tally the counts of jatha members and rogue protesters.

The right to protest

Farmer’s protest in Delhi precedes the government’s obliging to the demands made by farmers. In November 2020, farmers from all over India, centred in the capital, protested the three farm laws and demanded a right to MSP (Minimum Support Price). After more than a year of rigorous protests in heat, cold, or rain, the protesters won, and the government was forced to repeal the three farm laws.

The victory of farmers’ protests established a renewed faith in the democratic right to protest. It almost seemed possible that the people of a democratic nation could protest laws that do not suit them or that they do not agree with. But this defeat did not sit well with the party in power. Since then, any mention of a protest has been met with brutal hegemonic force to shut it down and scatter the demonstrators.

To satisfy the egoistic need of a patriarch, many democratic voices have either been silenced through brute force or systematic hegemony like raids or prisons. The hierarchy of authoritarian democracy has evidently no space for protests to prosper.

“We want the government to let us exercise our democratic right to protest,” said Pandher while explaining how the protest and the march were eventually a result of unheard demands. “In February, we held four rounds of talks with the government, but since then, there have been no further discussions on our demands.”

The demands of farmers that have not been met

In addition to the Minimum Support Price for their crops and timely delivery of the government’s promised guarantees, the farmers are seeking a 10 percent allocation of plots and a 64.7 percent hike in compensation under the previous land acquisition law, equivalent to four times the market rate. For land acquired after January 1, 2014, they are asking for 20 percent of the plots.

In addition to the relaxation in existing land rates and revised land allocation rates, the farmers’ demands include employment and rehabilitation benefits for the children of landless farmers, implementation of directives issued by the High-Power Committee, and proper arrangements for resettling inhabited areas.

In a nation such as India, where agriculture sustains two-thirds of the country’s 1.4 billion people and contributes nearly a fifth of its GDP, farmers encounter indifference and brutality. There is a lack of a justifiable representation for farmers in India, where their demands are discussed and solutions are provided.

They are not provided platforms to voice their opinions or seek reforms for their current situation. While some people view these protests with suspicion, and the government tries to shut them down any chance they get, where must the farmers communicate their demands?

In 2020, the protest underwent such brutal media trials that the farmers had to employ their own media channels. They would document and record every atrocity and their lives in general at the protest site. The ignorant view of the government leaves them unheard. In a democracy where people must reign supreme, they are subjected to barricades and tear gas when they set out to resist and protest the laws mindlessly passed by the government.

If there is one thing the government is undermining through its power tactics, it is the resilience of the farmers and their zeal to fight for their cause. After the Sunday fiasco, the protest garnered support from other organisations and leaders like Tikait, who supported the farmer protest and its cause.

With the Bharatiya Kisan Union’s backing, the protest has grown more substantial, and prominent leaders like Lakhowal and Ratanman have joined the growing agitation. One would hope that after the 2020 protest, the government would understand how force could not be solely used to discredit and deter protests. The barricades and tear gas have only reinforced the idea of justice, making the farmer’s resolve more strong to fight for their cause and win the battle of injustice.

About the author(s)

Dr. Guni Vats is an Assistant Professor at the Department of English, Manav Rachna International Institute of Research and Studies. A PhD in Gender Studies, she is a renowned researcher, writer, and scholar.