I’ve been staring at this blank document for hours now, trying to find the right words to begin. How do you start talking about something you’ve spent most of your life trying not to talk about?

Yet here I am, having spent years making myself smaller, more palatable, more invisible.

The burden of silence: Navigating caste in early life

I come from a small rural town in Kerala. But for most of my life, up until my college years, I was raised in the state of Goa. Childhood, for me as for most of us, was a time when I was still making sense of the intricacies of my identity. Geographical displacement had temporarily, but not wholly, shielded me from the reality of caste. At home, caste was a topic that rarely ever made it to the dinnertime conversations, except for when some distant relatives’ marriage prospects were to be discussed.

My parents never explicitly told me to hide who I was, but there were times when I was made to confront this aspect of my identity. “We are simple people; never forget that,” were the words of advice my father gave me when I was moving out for college. When I told my mom of my dream to become an engineer, her response was, “A padiyan’s child should not dream so much.”

For a long time, I thought my parents were incapable of understanding me or the dreams that I had. But now, after years of introspection, learning, and unlearning, I understand where these words were coming from. I know now that the hundreds of years of casteism and generational trauma can manifest as a tendency among Dalits to accept or rationalise their societal position, sometimes even viewing it as destiny and their fair share in life. This form of mental enslavement is passed down through generations like an heirloom.

The reservation question: Caste in school

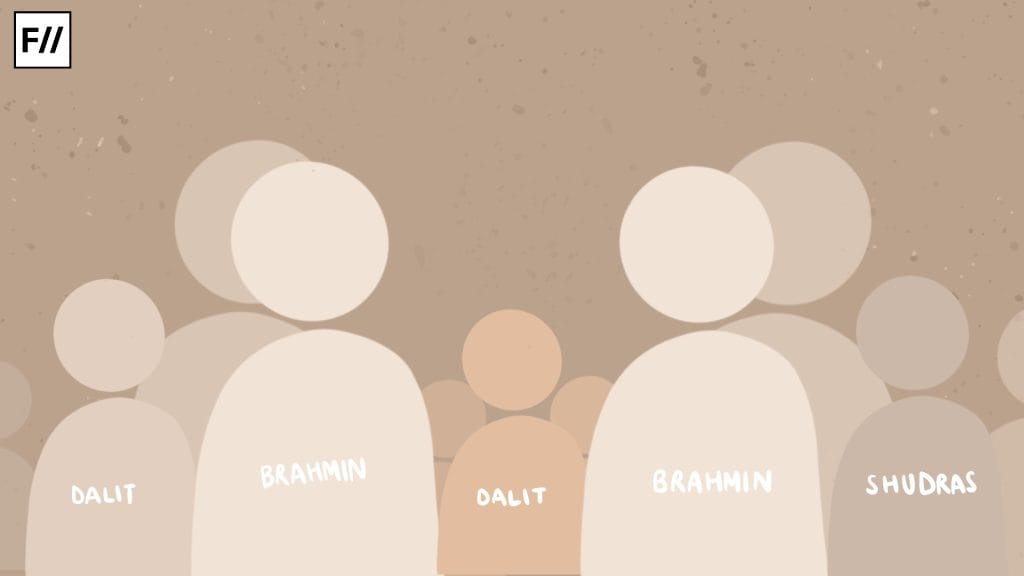

“One of the first institutions in India that silences the stories of the Dalit community is the school,” said Yogesh Maitreya in his memoir, “Water In A Broken Pot.” School, for me, was also the first institution that silenced my voice as someone belonging to the Dalit community. I was one of the only two Dalit students studying in my class. When my friends learnt of my caste identity, I still vividly remember their subtle, but obvious, shift in tone.

My entire group of friends consisted of Savarna students. And for them, the biggest obstacle for an advanced India was reservations. Throughout my school life, I was so adamant about fitting in with these kids that I would try to hide my caste identity and sometimes even go so far as to join in with them as they blamed reservations for everything wrong the country was going through.

I was, for a long time, living a double life. I, subconsciously, was aware of the position I occupied within this social structure. I was an outsider who made significant efforts to blend in. Every time I joined my peers in blaming the reservation system, I felt a deep-seated ache in my heart. Yogesh Maitreya spoke about this dichotomy when he said, “For a Dalit person, his identity is always in transition as he steps out of his home.”

At the crossroads of identity and political awakening

My reason for anonymity started at a young age. It was the subtle othering of my identity that my school and my peers subjected me to that ingrained this fear within me. Even as I dabbled with my supposed political awakening as a left-leaning individual, I rarely ever spoke out about issues when they included caste. I was a vocal supporter of the communist ideology and used to post extensively on social media about the islamophobic and anti-muslim stance of the right-wing government.

But when it came to issues about caste, I was always a bit hesitant. It was easier for me to speak and argue about issues that did not directly affect me or my identity. But when I had to speak out about issues that were at the core of my existence, I was reluctant to make that space for myself.

Caste is such an evil that it makes the oppressed feel ashamed of even asking for equality and a right to life. I was determined to distance myself from the oppressed.

Standing on the shoulders of giants: Discovering anti-caste literature

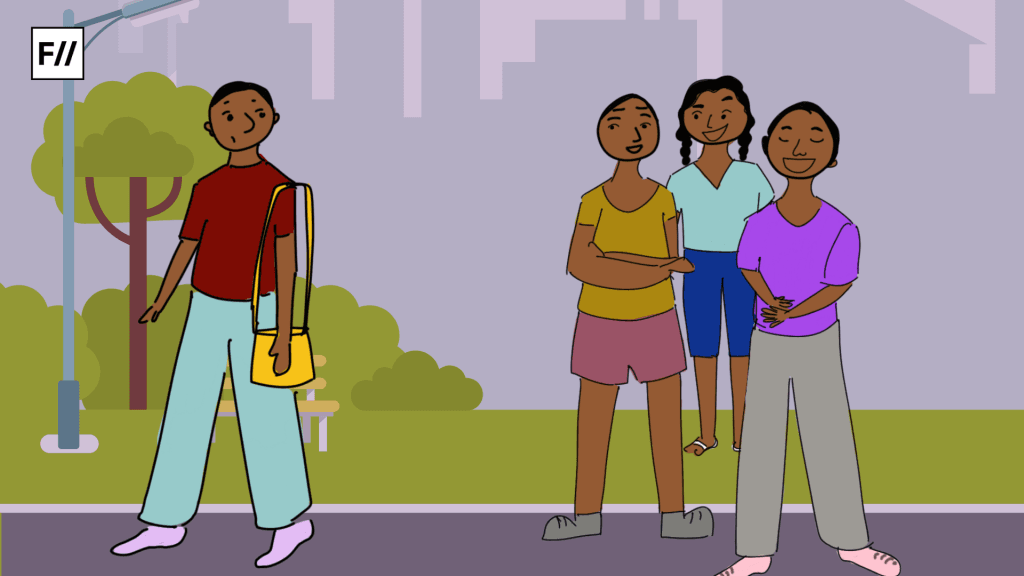

College brought a different understanding about caste in my life. I moved back to my hometown for college. It was here that I was faced with the more extreme side of caste and how deep it had laid its roots in our social fabric. In college, I met numerous others on my campus who belonged to the Dalit community. Being with people of my same identity brought a sense of safety and security that I rarely ever felt before as a teenager. Conversations about caste, even though rare, were still present.

It is quite ironic that my introduction to the father of caste liberation came through the works of a Savarna writer. During the first few months of my college days, I was obsessed with Arundhati Roy and her works. While going through her numerous books and collections of essays, I stumbled upon “The Doctor and the Saint.” The book has had many critiques for its portrayal of Ambedkar. But it was through this book that I read about the Khairlanji massacre, where a Dalit family—the Bhotmanges—was brutally attacked, leading to the murders of four family members. The visceral details of the abuse and violence are something that I would not like to go into detail here. But as I read more about the massacre and numerous others like this, I could feel a sense of belittlement as I read the history of what Dalits, as a community, had gone through.

The most transformative moment came when I finally read “Annihilation of Caste” in its entirety. His words, “I was born a Hindu, but I will not die a Hindu,” struck me with the force of revelation. Here was a man who understood that identity could be both inherited and chosen, both burden and power. It helped me understand my own journey—how my urban upbringing had distanced me from my identity.

Upon reading contemporary Dalit authors such as Meena Kandasamy, Suraj Yengde, Namdheo Dhasal, or Yogesh Maitreya, I observe how they build upon Ambedkar’s foundation while forging their own paths to resistance. Their works, along with Ambedkar’s, have taught me that accepting one’s identity isn’t about wearing it as a badge or hiding it in shame—it’s about understanding its place in the larger struggle for human dignity.

From anonymity to acceptance

As I spent more time in my hometown, I witnessed forms of casteism that pervaded the social landscape of rural areas in Kerala. My aunt, who worked as a domestic worker in different households, held pride in the fact that she would only sit on the floor in front of “the big people” at whose houses she went to work. My cousins would recall incidents from their childhood when they would walk to school and some random old man would remark, “The smell of books will never hide a padiyan’s smell.”

To my anonymity, I owe an apology. It has been part of my mind’s cultivation, a temporary shelter while I learn to stand in my truth.

For years, I was cocooned from the explicit caste politics of my rural hometown. But even then, caste had made its way into my life. It was there in the shame that I had harboured about my identity. It was there in the political conversations that I had with my friends as we consciously sidestepped topics about caste atrocities. It was in the reluctance that I have whenever I share some anti-caste post on my social media. Caste is the reason for me choosing to remain anonymous as I write this article. I understand that this shame, reluctance, and invisibility are all a result of the generations of casteism that my people have had to face.

To my anonymity, I owe an apology. It has been part of my mind’s cultivation, a temporary shelter while I learn to stand in my truth. It is a result of the shame that I harbour in my mind regarding my identity. Perhaps, as I learn to accept and wear my identity with pride, my journey from anonymity to acceptance will unfold naturally.

Maybe someday I’ll be ready to remove this veil of anonymity. Until then, I take comfort in knowing that even Ambedkar’s journey from Mhow to Maharashtra, from Columbia to the Constitution, was a gradual one. In my case, perhaps anonymity is an act of cowardice but a necessary one that, at the end of the day, is a result of the ubiquitous caste system. Maybe one day I shall learn to shed it and understand my place within this social structure.